“One of the most difficult parts of my job is enrolling patients into studies,” says Nicholas Borys, chief medical officer for Lawrenceville, N.J., biotechnology company Celsion, which develops next-generation chemotherapy and immunotherapy agents for liver and ovarian cancers and certain types of brain tumors. Borys estimates that fewer than 10% of cancer patients are enrolled in clinical trials. “If we could get that up to 20% or 30%, we probably could have had several cancers conquered by now.”

Clinical trials test new drugs, devices, and procedures to determine whether they’re safe and effective before they’re approved for general use. But the path from study design to approval is long, winding, and expensive. Today,researchers are using artificial intelligence and advanced data analytics to speed up the process, reduce costs, and get effective treatments more swiftly to those who need them. And they’re tapping into an underused but rapidly growing resource: data on patients from past trials

Building external controls

Clinical trials usually involve at least two groups, or “arms”: a test or experimental arm that receives the treatment under investigation, and a control arm that doesn’t. A control arm may receive no treatment at all, a placebo or the current standard of care for the disease being treated, depending on what type of treatment is being studied and what it’s being compared with under the study protocol. It’s easy to see the recruitment problem for investigators studying therapies for cancer and other deadly diseases: patients with a life-threatening condition need help now. While they might be willing to take a risk on a new treatment, “the last thing they want is to be randomized to a control arm,” Borys says. Combine that reluctance with the need to recruit patients who have relatively rare diseases—for example, a form of breast cancer characterized by a specific genetic marker—and the time to recruit enough people can stretch out for months, or even years. Nine out of 10 clinical trials worldwide—not just for cancer but for all types of conditions—can’t recruit enough people within their target timeframes. Some trials fail altogether for lack of enough participants.

What if researchers didn’t need to recruit a control group at all and could offer the experimental treatment to everyone who agreed to be in the study? Celsion is exploring such an approach with New York-headquartered Medidata, which provides management software and electronic data capture for more than half of the world’s clinical trials, serving most major pharmaceutical and medical device companies, as well as academic medical centers. Acquired by French software company Dassault Systèmes in 2019, Medidata has compiled an enormous “big data” resource: detailed information from more than 23,000 trials and nearly 7 million patients going back about 10 years.

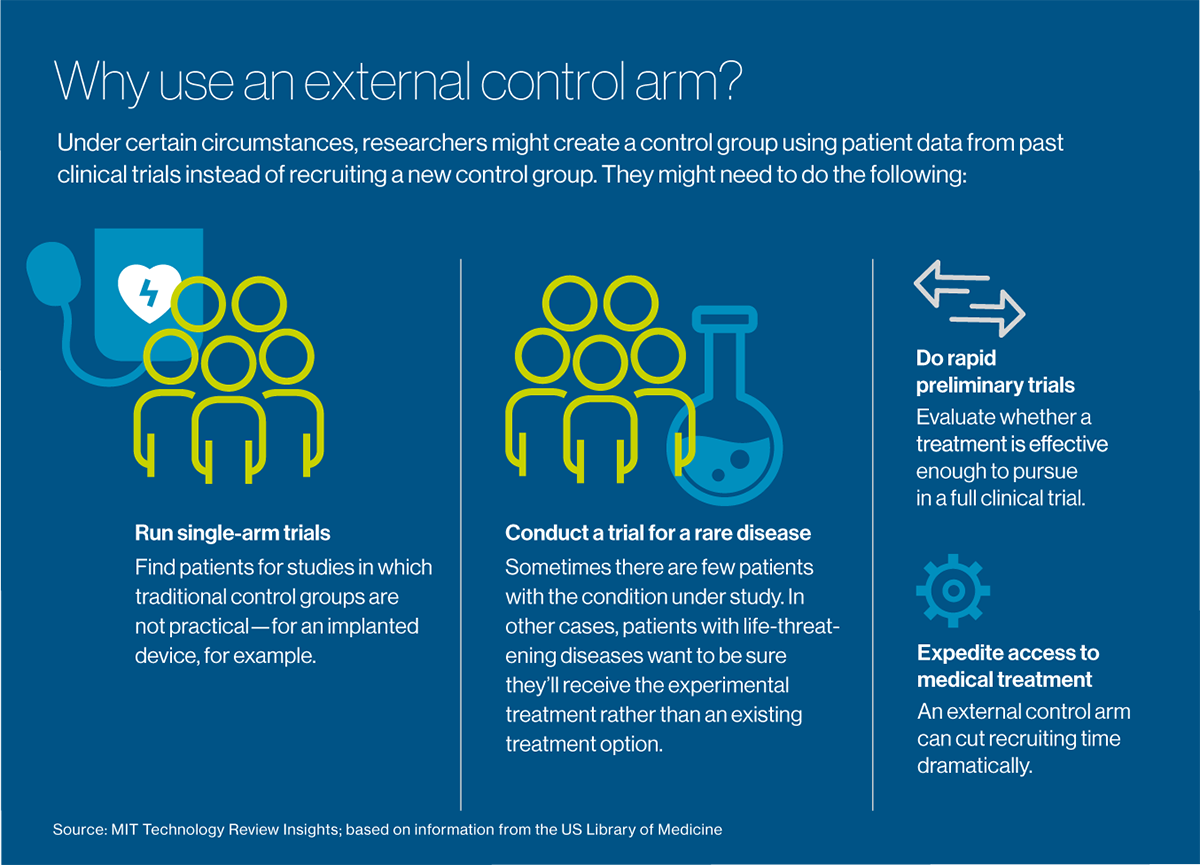

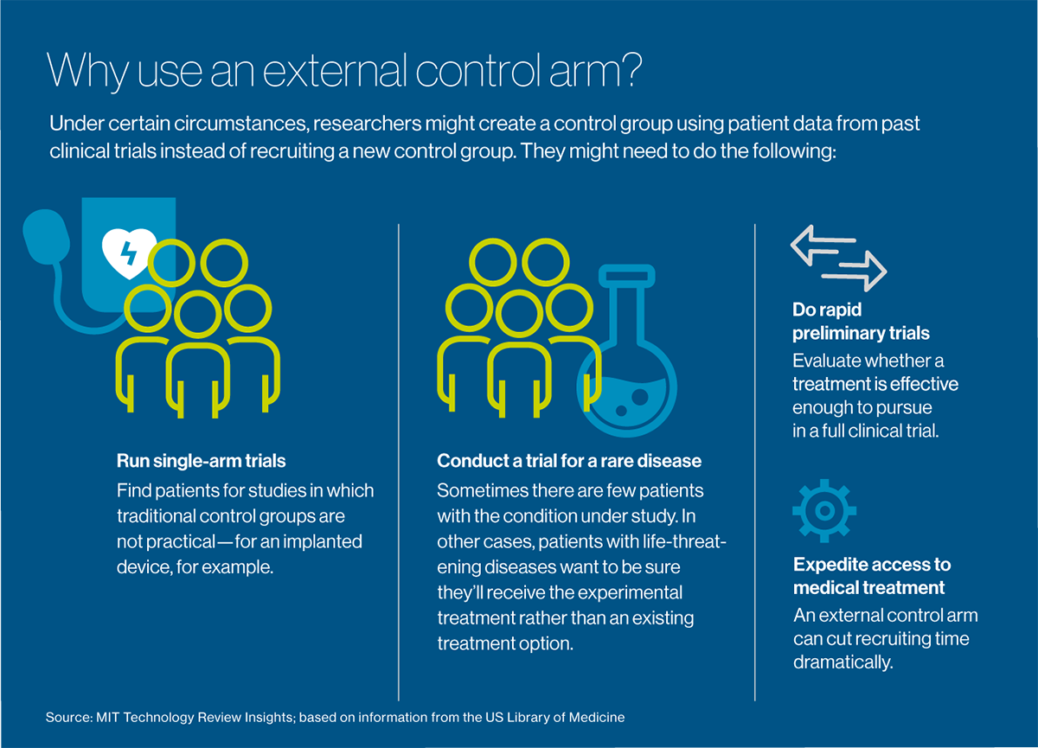

The idea is to reuse data from patients in past trials to create “external control arms.” These groups serve the same function as traditional control arms, but they can be used in settings where a control group is difficult to recruit: for extremely rare diseases, for example, or conditions such as cancer, which are imminently life-threatening. They can also be used effectively for “single-arm” trials, which make a control group impractical: for example, to measure the effectiveness of an implanted device or a surgical procedure. Perhaps their most valuable immediate use is for doing rapid preliminary trials, to evaluate whether a treatment is worth pursuing to the point of a full clinical trial.

Medidata uses artificial intelligence to plumb its database and find patients who served as controls in past trials of treatments for a certain condition to create its proprietary version of external control arms. “We can carefully select these historical patients and match the current-day experimental arm with the historical trial data,” says Arnaub Chatterjee, senior vice president for products, Acorn AI at Medidata. (Acorn AI is Medidata’s data and analytics division.) The trials and the patients are matched for the objectives of the study—the so-called endpoints, such as reduced mortality or how long patients remain cancer-free—and for other aspects of the study designs, such as the type of data collected at the beginning of the study and along the way.

When creating an external control arm, “We do everything we can to mimic an ideal randomized controlled trial,” says Ruthie Davi, vice president of data science, Acorn AI at Medidata. The first step is to search the database for possible control arm candidates using the key eligibility criteria from the investigational trial: for example, the type of cancer, the key features of the disease and how advanced it is, and whether it’s the patient’s first time being treated. It’s essentially the same process used to select control patients in a standard clinical trial—except data recorded at the beginning of the past trial, rather than the current one, is used to determine eligibility, Davi says. “We are finding historical patients who would qualify for the trial if they existed today.”

Download the full report.

This content was produced by Insights, the custom content arm of MIT Technology Review. It was not written by MIT Technology Review’s editorial staff.

Recent Comments