Severe illnesses and deaths from Covid-19 spiked on the West Coast in the weeks after catastrophic wildfires raged across the region last year, a study published Friday finds.

The increases in disease and death, the researchers say, appear to have been aggravated by the smoke that blanketed parts of California, Oregon and Washington during the 2020 wildfire season.

Full coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic

The new research was published in the journal Science Advances as Covid-19 cases are once again surging — driven by the highly contagious delta variant of the coronavirus — and massive wildfires blaze across the West, sending plumes of smoke all the way to the Eastern Seaboard.

Wildfire smoke contains microscopic particles that lodge in the deepest part of the lungs, where the oxygen exchange between the lungs and the blood occurs. That, along with the sheer density of the particles in wildfire smoke, makes the pollutant especially dangerous for respiratory health.

To compare wildfire smoke exposure to Covid-19 cases, the authors of the study looked at daily levels of the microscopic particles from wildfire smoke in nearly 100 counties in California, Oregon and Washington during the 2020 wildfire season and compared them to Covid-19 cases and deaths in the same period, as well as the four weeks that followed. They found that the burst of air pollutants correlated with a spike in Covid-19 cases and deaths that lasted up to four weeks after the smoke had cleared.

Some areas were covered in wildfire smoke for nearly one-third of the days from March to December. Butte County, California — where the Dixie Fire is raging — and Whitman County, Washington, had the sharpest spikes in Covid-19 cases following wildfire smoke pollution. The researchers estimated that wildfire smoke accounted for a nearly 20 percent increase in Covid-19 cases in each county.

“When you look at each individual county, there’s the possibility that there are other factors, such as a lot of dust, that could also be contributing to the rise,” said a co-author, Kevin Josey, a postdoctoral research fellow in the biostatistics department at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University. “But when you aggregate so many counties together and see those effects across the region, the possibility of coincidence becomes much more muted.”

Two earlier studies, one that focused on wildfire smoke pollution and Covid-19 cases in Orange County, California, and the other in Reno, Nevada, documented the same pattern.

“About two weeks after we had these smoke exposure events, we saw an uptick in the Covid-19 incidents, even in a low-density pollution area, that were beyond what you would have predicted normally. And then as the smoke dissipated, the peak went back down,” said Michael Kleinman, a co-director of the Air Pollution Health Effects Laboratory at the University of California, Irvine, who co-wrote the Orange County study. “This happened three times with three different smoke exposures.”

‘A completely different beast’

Sarah Henderson, scientific director of Environmental Health Services at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, said: “Wildfire smoke is so vastly different from the air pollution in urban areas or around industrial facilities that we usually talk about. It’s not another form of air pollution. It’s a completely different beast.”

That’s because, unlike the relatively predictable emissions from car or industry pollution, wildfire smoke changes constantly and the duration and amount of exposure really varies, she said. Wildfire smoke is also dense and can quickly increase fine particulate matter in the air twentyfold.

Kleinman said a growing body of evidence points to an association between wildfire smoke and susceptibility to Covid-19, although more research is needed to pin down whether there’s a direct link.

“The research does indicate that the particulate matter and toxic chemicals that are associated with wildfire smoke could have either helped with the transmission of the virus or made people more susceptible to an infection,” he said. “When you have wildfire smoke, you have all these particles in the mix, and there is a high likelihood that a virus could attach to these particles and travel further [through the air] than it otherwise would have.”

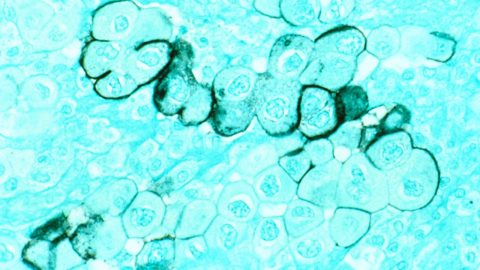

Henderson added that wildfire smoke “gums up the upper respiratory tract epithelium” — a thin layer of cells that’s covered in phlegm and mucus, the body’s first line of defense to keep viruses out of the body. Inhaling smoke also triggers an immune response in the lungs, which may weaken the immune system’s ability to fight the coronavirus, making it easier for an infection to take hold.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic

The authors of the new study noted that people with heart or lung disease, children and the elderly are particularly susceptible to the health impacts of wildfire smoke.

But Henderson stressed that the risk goes far beyond those populations.

“Everyone is potentially at risk when it’s smoky,” she said. “The risk is small for any individual, but because millions of individuals are exposed, those risks add up when you’re talking about whole populations.”

She also warned that experts need to look at the findings from last year in the context of the new, more contagious variants circulating this year. The hypertransmissible delta variant, which accounts for more than 90 percent of new cases in the U.S., didn’t exist last year.

In the short term, the best thing people can do to protect themselves is to get vaccinated against Covid-19. “There’s nothing that says wildfire smoke negates vaccination,” said Josey of Harvard.

But looking to the future, to mitigate the dangers of wildfires, the solution is to address the issues contributing to climate change, he said.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Recent Comments