HONG KONG — America’s new security alliance with Australia and Britain was always likely to be greeted with fury by China, the unspoken target of Washington’s latest effort to reinforce its influence in the region.

And it was. But the pact also incensed France, a longtime ally that felt its Indo-Pacific interests had been torpedoed by the submarine-centered agreement.

The French canceled a gala in Washington D.C. that was planned for Friday to mark the 240th anniversary of the Battle of the Capes, a critical French naval victory that helped the colonists win the American Revolution, the French embassy confirmed.

At a news briefing Thursday, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said the pact “seriously undermined regional peace and stability, exacerbated the arms race and undermined international nuclear nonproliferation efforts.”

Zhao added that any regional alliance “should not target or harm the interests of third parties.”

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

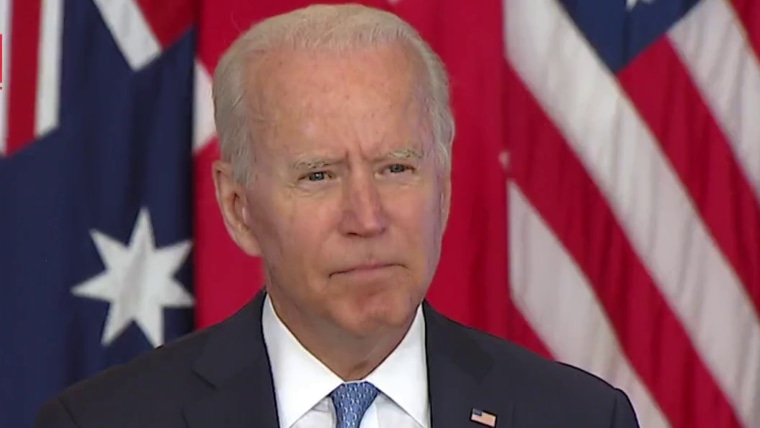

In a briefing before Wednesday evening’s announcement, a Biden administration official stressed that the pact “is not aimed at any one country.”

But the AUKUS deal comes as the United States steps up its efforts to counter China.

It will allow Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines for the first time, using technology that the U.S. had only previously shared with Britain. The pact also allows for greater collaboration among the three countries on cyber capabilities and artificial intelligence, as well as in other areas.

It will also make Australia the seventh country in the world to have nuclear-powered submarines, after the U.S., Britain, France, China, India and Russia. Unlike those other countries, Australia does not have nuclear weapons.

“The U.S. has only ever shared this technology with the U.K., so the fact that Australia is now joining this club indicates that the United States is prepared to take significant new steps and break with old norms to meet the China challenge,” Sam Roggeveen, director of the International Security Program at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, said in a statement shared with NBC News.

Relations between Beijing and Canberra have been in a downward spiral, with the U.S. ally emerging as a key bulwark in the West’s efforts to combat China’s growing influence.

China, Australia’s biggest trading partner, has embarked on a trade war in return.

There now appears little prospect for improved ties, which the Australian government will have taken into consideration, according to Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst in defense strategy and capability at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra, the Australian capital.

“I think China will probably increase the pressure on us as a result of this, but frankly we need to do this in order to ensure our security,” he said.

But it’s not just China that was irked by the deal.

France also expressed outrage after the agreement brought its own deal to build submarines for Australia, inked in 2016, to an abrupt end.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly voiced their displeasure in a joint statement.

“The American choice to exclude a European ally and partner such as France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region,” they said, “shows a lack of coherence that France can only note and regret.”

A visibly angry Le Drian later described the announcement as “a stab in the back.”

“This brutal, unilateral and unpredictable decision reminds me a lot of what Mr. Trump used to do,” he said on France-Info radio.

“We built a relationship of trust with Australia, and this trust was betrayed,” he added. “This is not done between allies.”

Parly said Thursday that the government would try to minimize the financial impact of the canceled deal on the submarine manufacturer Naval Group, which is mostly state-owned.

Asked whether France would seek compensation from Australia, she did not rule it out.

Being sidelined by the new alliance was a “big disappointment” for French trade, according to Frédéric Charillon, a political science professor at France’s Clermont Auvergne University.

“But, what is probably more worrying now is … the lack of confidence that is now growing between the Biden administration and at least some of the European alliance, including France,” he said.

Washington appears to be fueling “the impression that maybe the new administration (is) not that different from the last,” Charillon added.

In New Zealand, opposition leaders questioned why Australia’s neighbor and close ally had been left out of the loop.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said that her government had not been approached as part of the pact, “nor would I expect us to be.”

But she added that any nuclear-powered submarines Australia acquired would not be allowed in the country’s territorial waters, since its long-standing nuclear-free policy forbids the entry of vessels powered by nuclear energy.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said that in spite of the hard feelings among both rivals and some allies, this was simply an opportunity his country couldn’t turn down.

The advantages of nuclear submarines were clear, he said: “They’re faster, they have greater power, greater stealth, more carrying capacity.”

“Australians would expect me as prime minister to ensure that we have the best possible capability to keep them safe and to be unhindered in pursuing that as best as I possibly can,” he added. “And that is what I have done.”

Jennifer Jett reported from Hong Kong, and Chantal Da Silva reported from Toronto.

Recent Comments