A federal waiver that made school breakfasts and lunches free to students regardless of their family’s income is set to expire June 30, eliminating a benefit that has helped millions of schoolchildren at a time when they need it more than ever, anti-hunger advocates say.

The free school meals program began in March 2020 when Congress authorized the U.S. Department of Agriculture to issue dozens of child nutrition waivers, including ones that expanded summer food programs, to provide a lifeline during the pandemic.

If the waivers end this month as scheduled, experts foresee a crisis as families, already facing soaring prices at supermarkets, gas stations and elsewhere, lose access to meals that their children have counted on for the last two years.

The cafeterias that serve students, meanwhile, are already running into obstacles: Supply chain interruptions have driven up the cost of their foods dramatically and made it difficult for them to comply with the strict meal requirements set forth by the USDA. The waivers gave them flexibility to provide nutritious meals using substitutions without penalties.

“School meal programs are facing a perfect storm,” said Diane Pratt-Heavner, spokesperson for the School Nutrition Association, a trade organization representing more than 50,000 school nutrition employees.

“They are very concerned about financial sustainability,” she said, and with universal free meals going away, “they’re very concerned about kids going hungry next year.”

Before the child nutrition waivers, children in families whose incomes were at or below 130% of the federal poverty level were eligible for free school meals, while those in families whose incomes were between 130% and 185% of the poverty level were eligible for reduced-price meals through the USDA’s National School Lunch Program.

About 21 million students accessed free or reduced-price lunch each school day prior to the pandemic, said Jillien Meier, director of No Kid Hungry partnerships and campaign strategy. But up until 2020, enrolling students could be burdensome, both for parents who had to show proof that they qualified and for schools that collected the information, something that would be even more difficult now amid staffing shortages.

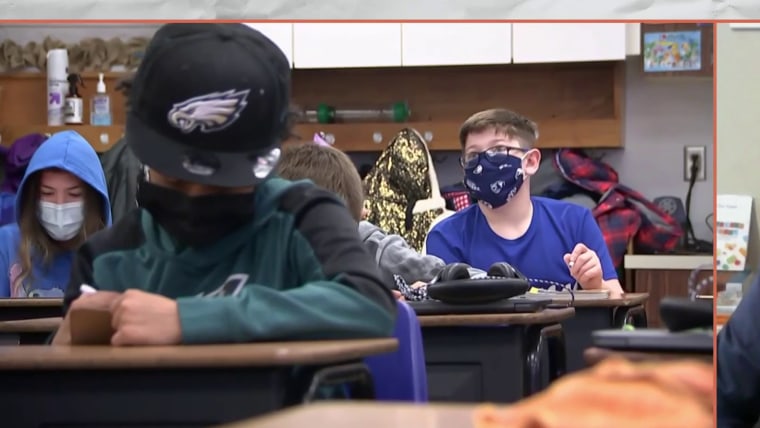

For the past two years, parents have not had to fill out applications. And because every student at their school was offered free breakfast and lunch, it reduced the stigma that some students had previously associated with receiving meals, Meier said.

The waivers allowed schools to distribute grab-and-go meals when they went remote. They are credited with helping avert what many feared would be a catastrophic spike in child hunger when the pandemic hit.

“We think that that is directly attributed to the flexibilities Congress gave,” Meier said. “And now they’re refusing to extend those waivers.”

USDA’s authority to issue waivers was expected to be extended for another year by President Joe Biden. But the extension was not included in the omnibus spending bill passed by Congress. POLITICO reported that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and other Republicans opposed extending funding for the school meals due to its cost of approximately $11 billion; an aide to McConnell denied that to NBC News, saying there was never a proposal for him to reject.

USDA urged Congress for an extension.

“Without Congressional action, our tools to assist program operators are much more limited. USDA is looking at every tool at its disposal to ease the burden the pandemic has caused on school districts, but the magnitude of this problem requires Congressional action,” USDA said in a statement, adding that the department has been able to offer “a few narrow program flexibilities” as schools transition back to normal operations but it is assessing further ways to assist.

How much money have free meals saved families?

Advocates have long argued that the bracket that qualifies a family for free or reduced school breakfast and lunch is too narrow and already excludes many families who are having a hard time making ends meet. A family of four would have had to be earning $34,450 or less in the 2021 to 2022 school year to be eligible for free meals, or $49,025 or less to have been eligible for reduced-price meals, according to the School Nutrition Association.

The price of school meals varies across the country, and the most recent data available from USDA is from the 2016 to 2017 school year, when school breakfast cost an average of $1.48 and school lunch cost an average of $2.57. That would mean that for a family with two kids, the cost of breakfast and lunch would come to $8.10 a day, or $1,458 for a 180-day school year — though school meal prices have since risen, so the number would be higher today.

The benefits of a universal school meal program extend beyond its financial aspects, said Kellie Crawford, who teaches science and library to kindergarten through third graders in Spokane, Washington.

Prior to the pandemic, about 35% of the students in her elementary school qualified for free or reduced-price meals, Crawford said. Once free meals were made available to every student, there was a noticeable increase in her classes’ overall focus and energy level.

“We saw how amazing it was,” she said. “Our school staff — it’s easier for them to do their jobs. Our students are happier and healthy.”

“We saw how amazing it was. Our school staff — it’s easier for them to do their jobs. Our students are happier and healthy.”

She also said it was a relief to no longer see students stress about their lunch account balance being low or empty.

While some states, such as California, have passed universal free school meal programs and others have introduced legislation proposing them, advocates are hoping Congress will take action.

“Just like kids get a free bus ride to school and textbooks to learn from, they need a meal in the middle of the day to be able to focus on their studies,” Pratt-Heavner said.

Recent Comments