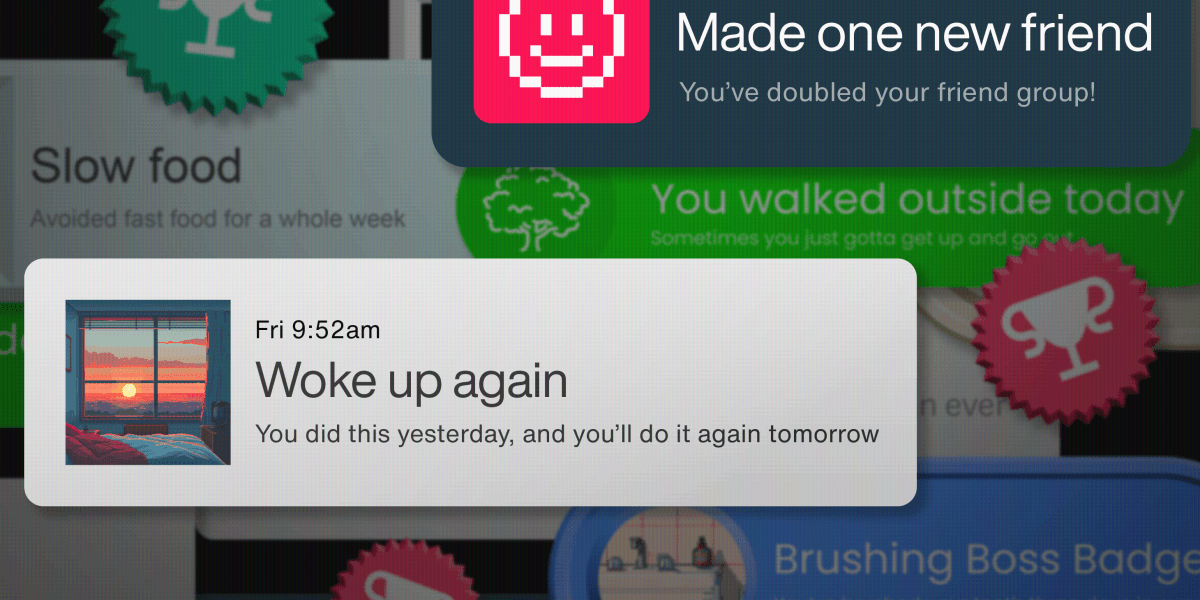

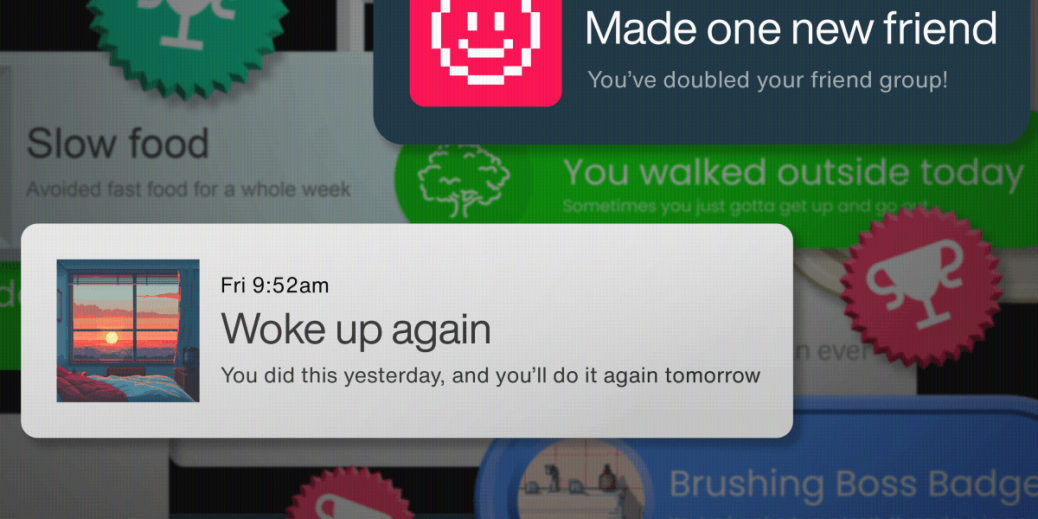

It’s a thought that occurs to every video-game player at some point: What if the weird, hyper-focused state I enter when playing in virtual worlds could somehow be applied to the real one?

Often pondered during especially challenging or tedious tasks in meatspace (writing essays, say, or doing your taxes), it’s an eminently reasonable question to ask. Life, after all, is hard. And while video games are too, there’s something almost magical about the way they can promote sustained bouts of superhuman concentration and resolve.

For some, this phenomenon leads to an interest in flow states and immersion. For others, it’s simply a reason to play more games. For a handful of consultants, startup gurus, and game designers in the late 2000s, it became the key to unlocking our true human potential. But instead of liberating us, gamification turned out to be just another tool for coercion, distraction, and control. Read the full story.

—Bryan Gardiner

This piece is from the forthcoming print issue of MIT Technology Review, which explores the theme of Play. It’s set to go live on Wednesday June 26, so if you don’t already, subscribe now to get a copy when it lands.

Why we need to shoot carbon dioxide thousands of feet underground

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) tech has two main steps. First, carbon dioxide is filtered out of emissions at facilities like fossil-fuel power plants. Then it gets locked away, or stored.

Wrangling pollution might seem like the important bit, and there’s often a lot of focus on what fraction of emissions a CCS system can filter out. But without storage, the whole project would be pretty useless. It’s really the combination of capture and long-term storage that helps to reduce climate impact.

Recent Comments