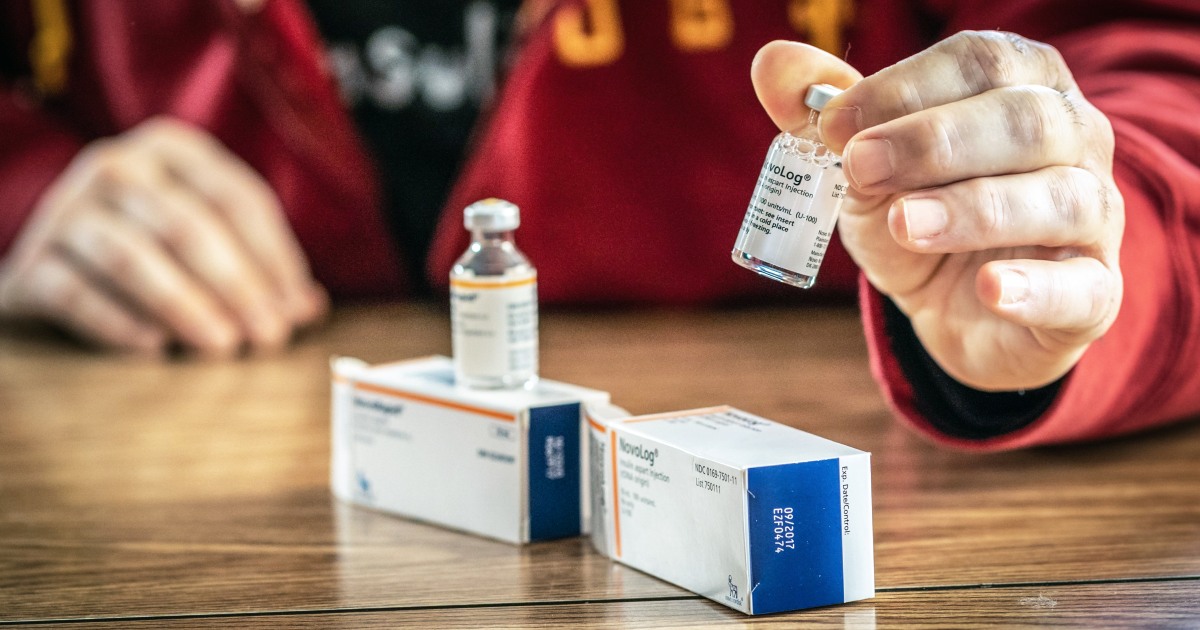

The axing of the insulin cap provision in the Senate’s budget reconciliation deal would leave millions of people scrambling to cover exorbitant out-of-pocket prices for the diabetes medication. Patient advocates were disappointed with Sunday’s vote — Republican senators blocked the $35 insulin cap for private insurers — and expressed hope that federal and state measures could be included in legislation down the road.

Clayton McCook of Edmond, Oklahoma, is among those who support capping the cost of insulin for people with private health insurance. His 14-year-old daughter, Lily, has Type 1 diabetes and needs insulin every day to stay alive.

A federal insulin cap for private insurance would have made “a huge difference to our family,” he said. The price of insulin is “a tremendous stress.”

About 53% of the public is in favor of Congress’ taking action to cap the out-of-pocket cost of insulin, according to a recent poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

A separate analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 1 in 5 insulin users on private health insurance pay more than $35 per month — or $420 a year — for the lifesaving medication. Patients usually need to buy multiple vials a month to maintain their health, which can sometimes cause costs to skyrocket.

“Insulin is too expensive for too many people with diabetes,” said Dr. Robert Gabbay, the chief scientist for the American Diabetes Association, an advocacy group for patients with diabetes.

All is not lost for people who struggle to cover the cost of insulin, but new legislation could still be years away, experts say.

Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., vowed to bring the measure back up for a vote this fall.

“They blocked a $35 price for insulin for non-Medicare people,” Schumer told MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow on Monday. “We’re going to come back and make them vote on that again.”

And Sherry Glied, the dean of New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, noted that “Congress can always change its mind.”

The final version of the Senate bill did leave in a $35 monthly cap on insulin for people 65 and older on Medicare. The bill would also allow the federal government to negotiate lower drug prices on behalf of Medicare, a measure that members of Congress have debated for decades.

“Some ideas take years to make their way into law but get there,” said Tricia Neuman, a Medicare expert with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Neuman co-authored a report published last month that detailed how the Senate’s reconciliation bill could affect both people on Medicare and people on private insurance.

She said that whether a provision succeeds largely depends on who the sitting president is, as well as the composition of Congress.

“This year, with an evenly divided Senate, the insulin cap for people with private insurance didn’t secure enough votes,” Neuman said. “That may not always be the case.”

McCook works as a veterinarian, and he is able to get his daughter insulin through his employee health insurance, but not before he shells out the $6,000 a year his plan requires before his insurance begins to pay.

Oklahoma is among the 22 or so states that have passed laws that cap copayments for insulin, but McCook noted that several of the state laws cover only people with state-issued health insurance plans. Experts are hopeful policies can be changed to include employment-based insurance plans.

Experts say the price of insulin— a more than 100-year-old medication — has remained high over the years because of the combination of an increasingly complicated supply chain and “evergreening,” a process in which drug companies make incremental improvements to their products that can extend the lives of their patents.

A study published last month in the journal Health Affairs found that 14% of people who use insulin in the U.S. face what is described as a “catastrophic” level of spending on the medication, meaning that after they pay for other essentials, such as food and housing, they spend at least 40% of their remaining income on insulin.

Other groups have pushed for policies that would have states provide emergency 30-day supplies of insulin to patients for $35. Such a bill, called the Alec Smith Insulin Affordability Act, has already been signed into law in Minnesota.

McCook also advocated for changes besides a cap on insulin costs, saying Congress pass legislation that would lower the list price.

The reconciliation budget “would have helped us, but it still leaves a lot of people out,” he said, noting that the provision wouldn’t help those who are uninsured.

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Recent Comments