Until recently, a prevailing theory about the severe hepatitis cases popping up in children suggested that an adenovirus was probably to blame.

Since April, many young kids with dangerous liver inflammation have tested positive for adenovirus 41, which typically causes coldlike illness or an upset stomach. But two studies released this month, which have not yet been peer-reviewed, outlined another theory: Some children may have been infected with an adeno-associated virus, which uses a second helper virus to replicate.

Researchers from Scotland and England detected one particular adeno-associated virus, called AAV2, in the blood and livers of U.K. children with severe hepatitis. The researchers suggested that some kids may have been co-infected with AAV2 and another virus like adenovirus 41 — a combination that could result in liver failure. The studies also identified a genetic marker that might put children at higher risk of this outcome.

But doctors aren’t sure if the cases themselves are novel. Even before this year, many pediatric hepatitis cases were a mystery — between 30% and 50% of such cases are from unknown causes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Liver failure always appropriately sounds horrific and should never happen, but it does happen, and it does happen without us often knowing the cause in children,” said Saul Karpen, a gastroenterology professor at the Emory University School of Medicine. “We do all the right studies. We can’t figure it out.”

Karpen said that approximately half of the acute hepatitis cases that typically show up to his hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, have no clear origin. Around 10% of those cases progress to severe liver failure and can require a transplant, he estimated. In a recent editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, Karpen called for more data to determine whether the recent cases are truly out of the ordinary.

In a report released earlier this month, the European CDC similarly said it is not clear whether the cases identified since April “are part of a true increase compared to the baseline rate.”

New insight into potential causes of this illness, then, might help address a longstanding medical mystery rather than a new one.

Are the recent hepatitis cases abnormal?

Since a spate of pediatric hepatitis cases sparked concern in the U.K. in April, the World Health Organization has detected more than 1,000 probable cases — including 22 deaths — across 35 countries.

Europe had recorded 473 cases by the end of June, mostly among children 5 years old and younger. Around half of those patients recovered, but 80 remained under medical care and 20 received liver transplants. A child in Ireland died of the condition in May, then another died in Greece this month.

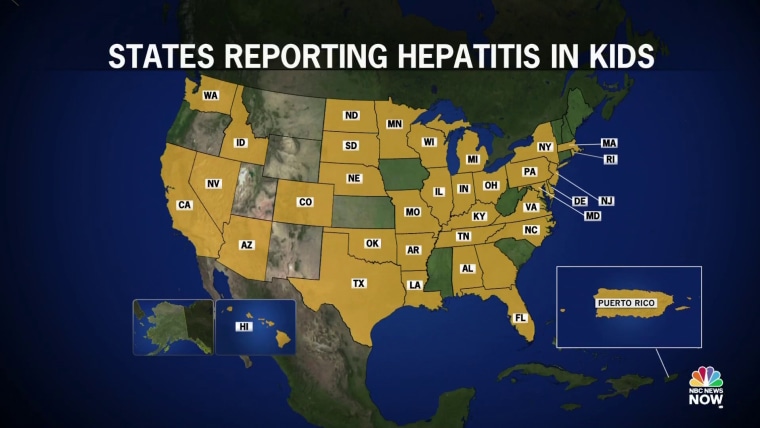

In the U.S., health officials were investigating more than 350 suspected cases of acute hepatitis in kids under 10 as of Wednesday, all of them recorded since October 2021.

But last month, the CDC said there was no sign that an increasing number of children were being hospitalized for hepatitis relative to rates before the Covid pandemic. From October 2021 to March 2022, the U.S. saw an average of 22 monthly hepatitis-related hospitalizations among children under 4, and 12 among children ages 5 to 11. The country recorded similar averages in 2019.

Some experts think hepatitis cases may have temporarily spiked once Covid restrictions lifted, because young children subsequently got exposed to viruses that their bodies hadn’t seen before.

“Imagine that everyone that would have gotten it over the last three years is only getting it this year,” said David Thomas, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

If that’s true, he continued, the recent cases could be “just the same old thing that we previously couldn’t explain.”

Karpen said it’s also possible that the recent spike in the U.K. was just part of the “natural history of a disorder that has not been followed with this degree of scrutiny before.”

The strongest theory yet

The new theory about pediatric hepatitis hinges on a small sample size: 37 patients across the two preliminary studies. But disease experts said the idea is intriguing.

Lishan Su, who directs the virology, pathogenesis and cancer division at the University of Maryland’s Institute of Human Virology, said it’s plausible that a combination of two viruses and a unique genetic marker would lead to liver inflammation.

Both studies found the AAV2 adeno-associated virus in nearly all blood and liver samples from children with mysterious hepatitis cases. And the study from Scotland did not find AAV2 in any blood samples from healthy kids or those admitted to the hospital for hepatitis with a known origin.

The association with AAV2 “seems to be really strong based on this small number of patients,” Su said.

The studies also detected low levels of adenovirus 41 and herpes virus in many of the liver and blood samples, suggesting one of those viruses could be helping AAV2 replicate. That might explain why other research detected adenovirus 41 among some pediatric patients.

A CDC report found evidence of adenovirus in 45% of children with mysterious hepatitis cases from October 2021 to June 2022, with adenovirus 41 being the most common subtype. A recent U.K. study found adenovirus in 90% of pediatric cases tested for it.

The genetic marker identified in the Scottish study helps determine the body’s immune response to viruses, so it could also be an important part of the story, Su said. The marker was found in eight of nine cases of mysterious hepatitis the researchers studied. By comparison, it was present in just 16% of Scottish blood donors. The second study also detected the marker in four of five cases that required liver transplants.

But even this new research leaves unanswered questions. Neither preprint study, for instance, found evidence of actual virus in the liver tissue of infected children. That could suggest that the immune response — rather than the virus itself — triggers liver damage. But there’s not yet proof of that, Karpen said.

Thomas said the full explanation could turn out to be messy, with kids getting sick for a variety of reasons.

“It’s a story that’s still being told,” he said. “We just had another chapter — a good chapter — but it’s not the end of the book.”

Still, understanding even some facets of severe hepatitis in kids would be a breakthrough, Thomas added.

“These kids are suffering. The families are suffering,” he said. “If we could just prevent half of it, that would be amazing.”

Recent Comments