Florida health officials reported two additional cases of malaria on Thursday.

Both were identified last week and neither was linked to travel outside the country. That brings the total number of locally acquired malaria infections in the U.S. to seven since May. All but one case has been in Sarasota County, Florida. The other case, which was not connected to the Florida ones, was a Texas man who was working for the National Guard along the Rio Grande.

The cases are the first in 20 years to be acquired in the U.S.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a health alert on June 26 asking hospitals to be on the lookout for patients with malaria symptoms and prepare to rapidly diagnose them and start administering antimalarial drugs within 24 hours.

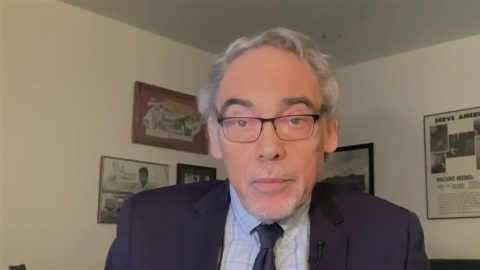

Dr. Manuel Gordillo, an infectious disease specialist at Sarasota Memorial Hospital, said his hospital has treated four of Florida’s malaria cases this year, including the first patient found to have the infection and the two most recent cases.

All were diagnosed shortly after they were admitted to the hospital, Gordillo said — unlike the Texas patient, who said he was initially misdiagnosed with a viral infection. A couple of the patients were homeless, Gordillo said, and arrived with fevers and dehydration.

“Some of the cases were sort of neglecting the symptoms and they presented way late with other complications,” he said.

To his knowledge, Gordillo said, public health officials aren’t actively searching for new cases unless they show up at a clinic or hospital. The Florida Department of Health did not respond to a request for information about how it’s monitoring for new cases.

Dyann Wirth, an infectious diseases professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said the new cases are somewhat surprising but not unheard of.

“This is not a panicking thing, but it’s also not something where we should say,’Well, it’s so unusual, we shouldn’t worry about it.’ It’s a warning to keep surveillance up,” Wirth said.

Malaria is a serious, sometimes fatal, disease usually transmitted by mosquitoes, which transfer a parasite to humans through bites.

Typical symptoms include fever, chills, headache, muscle aches and fatigue. Some patients also experience nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, according to the CDC. Symptoms typically appear 10 days to four weeks after being bit by a mosquito.

Before the Covid pandemic, the U.S. saw around 2,000 cases of malaria each year, though nearly all were in people who had traveled to other countries.

How are doctors treating malaria patients?

The recent U.S. cases were caused by a parasite called P. vivax, which is the dominant malaria parasite outside Africa. P. vivax isn’t as deadly as some other parasites that cause malaria, but it can lie dormant in the liver and cause chronic infections months to years after an initial illness.

Gordillo said doctors typically prescribe two treatments for P. vivax: one to kill the parasite in the blood, and another to kill the parasite in the liver.

The antimalarial drugs chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine are usually the first line of treatment, he said. But Gordillo said his hospital has faced supply challenges with those drugs, so it’s prescribing Coartem — a medication that’s more effective but costs more and isn’t available through pharmacies.

Gordillo said Coartem is a three-day treatment. After that, he said, patients receive a two-week treatment of a drug called primaquine, which can be taken at home. However, some patients have required lengthier hospital stays, he said.

“They are the dehydrated, some of them. They have low blood counts, especially platelets, which puts them at risk for bleeding. Some of them have had renal kidney failure, which is one of the complications of malaria,” Gordillo said.

Why are locally acquired cases appearing now?

Malaria was considered eliminated from the U.S. by 1951. The likeliest explanation for the new cases in Florida, Wirth said, is that a person with malaria traveled to the U.S., then was bitten by a local mosquito, which then spread the disease to other people with no travel history.

“Everything has to be right for transmission to occur,” Wirth said. “An infected person has to have the transmissible form in their bloodstream. The right kind of mosquito has to bite, and then that mosquito has to live long enough to bite another person.”

The average female Anopheles mosquito — the most common malaria transmitter — lives about two to three weeks, and it takes about seven to 10 days for a parasite to develop in the mosquito, Wirth said. The insects travel about 1.2 miles maximum, according to the CDC.

Gordillo said all six of Florida’s cases are from a northern region of Sarasota County, which has wooded areas and has experienced rain recently. Mosquito populations are usually largest in the summer, and Florida’s humidity is ideal for them to breed.

Both Gordillo and Wirth said there may be more cases that haven’t been diagnosed.

“We don’t know how long this is going to last because of the nature of this particular strain. It can hide in people’s bodies, the incubation period can be long, so it may linger a little bit,” Gordillo said.

Wirth said malaria “can be explosive” because one mosquito can infect many people, which is why it’s important to screen for new infections through routine blood samples, she said.

In some past outbreaks in other countries, Wirth said, screening programs ceased too early after case numbers dropped.

“Whoever was in charge kind of thought, ‘Well, we’ve got this problem mostly solved. It’s expensive to keep all this surveillance up,’ and there were massive rebounds,” she said.

The Florida Department of Health said last month that it is spraying insecticides to kill off mosquitos and advised residents to use bug spray, wear long sleeves and pants, and drain standing water.

Recent Comments