From her earliest memories, the misery of alcoholism has marred Karen Angus’ life. She was only a girl when her father, “a violent, unpredictable alcoholic,” died from drinking, leaving behind a wife who was abstinent and seven children who — in time — would be anything but.

“I lifted my first drink at 13, and my life was never to be the same again,” Angus said, her voice charged with emotion, speaking from her home in Glasgow, Scotland. A bright academic future soon faded, and, by age 15, alcoholism had her “by the throat.”

Over the next 30 years, the grip of addiction steadily tightened. Spurred by an irrepressible compulsion, she would binge on daily doses of cheap cider and vodka, consuming quarts at a time. The consequences were devastating: abusive relationships, job losses, criminal charges, hallucinations, hospitalizations and, eventually, homelessness.

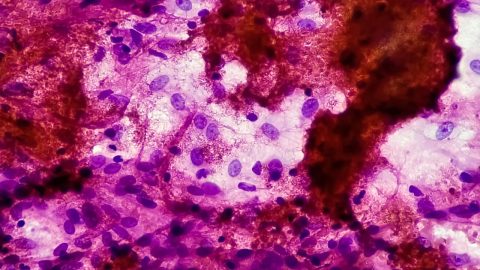

Decades of Angus’ memories have been lost to the inky darkness of booze-induced blackout, but some of her lowest moments — including hallucinatory bouts of delirium tremens, the most extreme form of alcohol withdrawal — are hard to forget.

“A couple times, I had to run out of my work, because the walls suddenly were closing in and all these monsters were coming for me,” she said. “I once stood outside a funeral parlor, because I thought I was going to die.”

By age 38, having lost her job, her house and her husband, Angus was at the end of the road, spiritually and emotionally. It was then that a close friend intervened and sent her to the doctors. It marked a turning point in her alcoholism but also the start of a prescription — and then illicit — drug addiction.

Eventually, with the help of counseling and group therapy, Angus got entirely clean, overcoming the demons that drove her destructive behavior.

In 2005, Angus lost her older sister to alcoholism. In Scotland, such stories are not unique.

After a period of marked improvement, Scottish alcohol-related deaths are again on the rise. Figures from 2018, released recently, reveal that 1,136 Scots died from alcohol-specific illnesses — 10 percent more than in 2012, when deaths reached a near-20-year low.

Scottish men are twice as likely to die from alcoholism as men in England, while Scottish women suffer an 87 percent higher alcohol-related death rate than their English counterparts.

The reasons are many. Scotland’s dreary weather is a potent if prosaic factor, some say, pointing to alcohol dependency as a historic means of coping with the country’s unforgiving climate.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Others, including clinical experts, lean more toward ingrained societal drivers.

“We’ve always had a heavier drinking culture in Scotland,” said Eric Carlin, the director of Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems, highlighting the so-called Glasgow effect.

Sociologists coined the phrase, a reference to the dismally poor public health record of Angus’ hometown, while examining the role of socioeconomic factors — housing, schooling, employment and, as Carlin puts it, an overarching “malaise” related to deindustrialization — in Glaswegians’ below-average life expectancy.

When it comes to Scotland’s wider drinking problem, the footprint is clear to see. According to figures for 2018, alcohol-specific deaths were almost five times higher in the 10 percent most deprived areas in the country, compared to its 10 percent most affluent areas.

The scale of the crisis is not lost on Scottish lawmakers, who have pursued ever stricter anti-booze policies. In May 2018, after years of legal wrangling, Scotland’s headline minimum unit pricing scheme was launched. Targeting low-cost, high-strength beverages, the new law set a minimum price of 50 pence (67 cents) per unit of alcohol.

Twelve months from its introduction, the policy was showing some positive results: The volume of pure alcohol sold per person had fallen by almost 4 percent, from 10.3 liters to 9.9 liters (from 10.8 quarts to 10.5). A significant rise in the price of cider (a drink that tormented Angus for 30 years) — up by about 13 pence (17 cents) per unit — seemed particularly effective, with sales of the drink dropping by nearly a fifth.

But progress seems to have stalled. In 2019, the second year of minimum unit pricing, there was no discernible fall in alcohol sales, with just less than 10 liters (10.5 quarts) of booze bought by the average Scot. That equated to around 19 units per adult per week — a full five units above government recommendations.

And now, as Scots emerge tentatively from COVID-19 confinement, there are worries that the sort of problem drinking that afflicts Angus’ family could again accelerate.

Gary Meek runs the Glasgow Council on Alcohol, a voluntary organization that helps the city’s alcoholics. During the lockdown, referrals to the council’s addiction service, which uses a harm reduction philosophy pioneered in America, increased by almost a fifth — and the worst could still be to come.

“Our self-referrals are up about 18 percent,” Meek said. “My suspicion is that that number will be increasing more when people are having to go back to work, having to drive, having to go to the office, and not being able to drink during the day anymore.

“I think we’re going to start seeing some more of these issues coming forward,” he said.

Survey data seem to bear out Meek’s fears. A poll conducted at the height of Scotland’s coronavirus restrictions revealed that almost a third of frequent drinkers (those who imbibe at least four times a week) were consuming more while under the lockdown.

For Angus, that comes as little surprise.

“Isolation is the worst thing for an alcoholic,” she said. “I’ve had to use recovery groups online during lockdown and encourage other people to use them, [but] they’re screaming out for face-to-face meetings.

“People are dying because of it.”

With a new wave of alcohol-related illness in the offing, experts say a fresh approach to supporting Scotland’s most chronic drinkers is warranted. Karyn McCluskey, a forensic psychologist, is pursuing precisely that.

Taking their lead from a program in Canada, McCluskey and her colleagues are working to establish Scotland’s first “managed alcohol project” — a service that gives chronic alcoholics regular measures of booze in a safe, monitored environment.

“We’re going to take these guys in, we’re going to give them dignity and respect, but we’re also going to give them the very thing they crave: drink,” McCluskey said.

Designed for those at the sharp end of alcoholism — people who invariably end up in the hospital, in prison or on the streets — the project will aim to gradually steer addicts away from the bottle while offering them a safe space and constant support. Because, as McCluskey put it, “the tears of their kids” would have stopped them drinking long ago if they could do so unaided.

Still, sobriety can be achieved only if a person “really wants it,” said Angus, the recovering alcoholic. She said that several people in her life have tried therapy but that none have stuck with it. And so, with a devastating sense of inevitability, she is resigned to the worst.

“I know they’re going to die,” she said. “I’ve seen it too many times in recovery, people who go out and lift a drink and don’t make it back.”

Recent Comments