The first man to receive a transplanted pig heart died of heart failure due to several factors, not organ rejection, leading the doctors involved in the trial to call it a success.

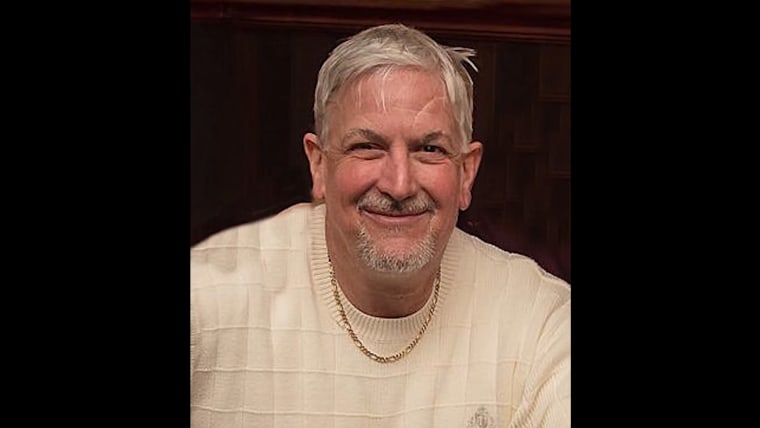

David Bennett, 57, received the genetically modified porcine heart on Jan. 7 after the Food and Drug Administration gave emergency authorization on New Year’s Eve.

Before the transplant, Bennett had been hospitalized for six weeks with a life-threatening arrhythmia and had been connected to a heart-lung bypass machine. He was in end-stage heart failure and did not qualify for a traditional heart transplant.

Doctors involved in the University of Maryland Medicine study published a paper last month that said a “complex array of factors” caused heart failure in the patient, according to a news release.

When the heart was first transplanted, “we were incredibly encouraged by his progress. His heart was strong, almost too strong for his frail body, but he had a strong will to live,” said study co-leader Bartley Griffith, a transplantation professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“Our findings on autopsy did not show evidence of rejection,” Griffith, who is also the clinical director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at the school, said. “Instead, we saw a thickening and later stiffening of the heart muscle leading to diastolic heart failure, which means the heart muscle was not able to relax and fill the heart with blood as it is supposed to.”

The heart may have failed due to a drug that is supposed to prevent rejection and infection, but might have damaged the muscle, according to the school.

“The heart was also found to contain evidence of DNA from a latent pig virus called porcine cytomegalovirus (pCMV) through highly sensitive testing that was first detected several weeks after the surgery and was later confirmed during autopsy of the organ,” the release said. Whether the virus damaged the heart is under investigation.

Infection control measures were in place before the transplant and the heart had been tested just before transplant. The infection, though, was confirmed during the autopsy.

“We consider this to be an important learning experience,” said study co-leader Muhammad M. Mohiuddin. “Knowing what we know now, we will alter some of our practices and techniques in the future.”

Xenotransplants, the term used for transplants from a nonhuman species to a human, have been researched as the demand for organ replacement increases. According to the FDA, 10 patients die per day while awaiting a donated organ.

Pig and cow tissues have been used successfully for valve replacements, according to Harvard University Medical School. Those valves typically last about 15 years and don’t require the use of anti-clotting drugs as opposed to a mechanical valve, which can last the rest of a person’s life.

“We have entered a new era in organ transplantation,” said Bert W. O’Malley, president and CEO of the University of Maryland Medical Center. “While we still have a road ahead before xenotransplantation becomes an everyday reality, this historic surgery brings a future many never thought possible within our reach.”

Recent Comments