BATON ROUGE, La. — Tiny babies as young as two weeks old are shepherded into the Pennington Biomedical Research Center’s lab in strollers and car-seat carriers. Some cry, some can’t stop wiggling, and others simply sleep during their entire visit.

Their job is easy: hang out while scientists take careful measurements of their body fat and metabolism.

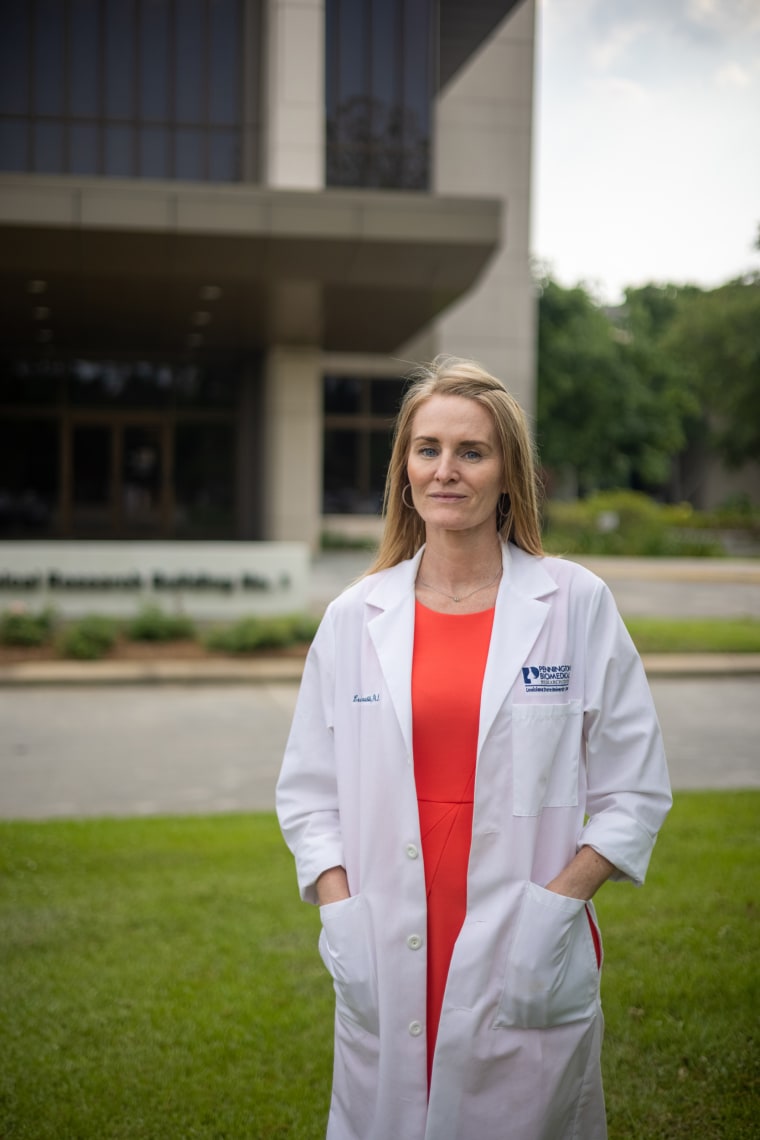

“We think that by studying babies, we can really get to the biology of obesity,” said Leanne Redman, who directs the maternal and infant research lab at Pennington here at Louisiana State University. It’s the only lab in the world equipped to study the metabolism of newborns. That is, how their tiny bodies burn energy, or calories.

Redman believes that by studying metabolism in the first weeks of life — long before a person’s weight is influenced by outside factors like the foods they are fed or choose to eat — the lab will uncover the biological basis of obesity. Newborns don’t exercise, and their diets are comprised solely of breastmilk or formula.

The theory is that a person’s “metabolic fingerprint” is set for life at birth, she said. Decoding that fingerprint could ultimately lead to personalized interventions for children at risk for obesity.

The ramifications are of critical importance to the future health of Americans. Obesity is a driver of myriad health problems, including heart disease, stroke, cancer and type 2 diabetes.

Despite millions of dollars spent each year on obesity research, prevention and treatment, America’s obesity epidemic continues to grow. Nationwide, it affects nearly 20 percent of children and teenagers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more than 40 percent of adults — a figure expected to rise to 50 percent by 2030.

“We’ve been living a silent pandemic over the past few decades,” said Dr. Andres Acosta, a bariatrician and gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. “It’s killing our generation.”

Biology versus behavior

The science of obesity and how to treat it is far from straightforward. The driving factors extend beyond diet and exercise, to a thorny metabolic mixture of a person’s genetics and environment.

“Weight is the product of its energy balance. It’s a basic physics equation: calories in and calories out,” Redman said. “What’s driving both of those factors — calories in and calories out — is very complicated. What is driven by biology and what’s driven by behavior?”

The Pennington lab’s location in Louisiana makes it uniquely positioned to study obesity. The state consistently ranks among the worst in the country in terms of obesity. Data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation shows that 22.2 percent of children ages 10 through 17 have obesity.

“Louisiana is a living laboratory for the rest of the world, whether that’s a good thing or not,” Redman said. “We have diversity in income. We have diversity in race. We have diversity in ethnicity, and we have diversity in health conditions.”

A better understanding of what drives obesity early in life or what factors put a child at risk for obesity later on are key for prevention, said Dr. Ryan Farrell, a pediatric endocrinologist at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“Getting a sense of kids that have lower resting energy expenditures early on, getting a sense about whether or not that infers long-term health consequences as kids get older could potentially mean intervening at an earlier age and putting in lifestyle modifications well before there is the development of rapid weight gain,” he said.

And the earlier physicians can intervene, the better.

“We see all these kids way too late,” said Dr. Evan Nadler, director of the Child and Adolescent Weight-Loss Surgery Program at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. “We deal with them the best we can and we get a lot of them to lose a lot of weight, but they get to us long after they should.” After age 5, Nadler said, it’s much harder.

That’s one reason why the Pennington Lab is focused on newborns.

Into the Pea Pod

Babies enrolled in the National Institutes of Health-funded study are first brought into the lab at just two weeks old for their first two measurements: body fat percentage and metabolism.

To calculate body fat, babies are placed inside an enclosed, oval-shaped chamber called a Pea Pod. The machine measures how much air volume the baby takes up inside the pod, compared to the baby’s body mass. The entire process takes 90 seconds.

The researchers plan to look at each baby’s body fat at just a few weeks old and compare it to how it looks at two years of age, Redman said. What is it about a newborn that might determine his or her body fat at 4 or 5, or even 25 years old?

So far, hundreds of babies have had their body fat measured in Pennington’s Pea Pod. Along with others in use globally, the team has data on approximately 7,000 babies.

But scientists worldwide are looking to Pennington for its research on the second measurement: newborn metabolism. The lab is the only one in the world using an infant metabolic chamber.

The infant chamber is meant to mimic the gold standard of measuring metabolism in adults. Those metabolic chambers are about the size of a small hotel room. Adult participants stay in the room for 24 hours, and scientists are able to calculate precisely how many calories they burn over that time period.

“We’ve been perfecting our protocols to be able to capture that entire cycle while the baby is in the metabolic chamber,” Redman said. In baby time, that’s about two hours.

The infant chamber is a plexiglass cube furnished with a tiny mattress and adorned with smiling elephants and lions. Parents and members of the Pennington lab can reach in to soothe the babies when necessary. Usually, they just sleep.

How metabolism is measured

A baby’s metabolism is calculated by taking precise measurements of the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the chamber. Researchers know the concentration of these gasses in the air when the baby goes into the chamber, and each exhalation contains more carbon dioxide than oxygen. By measuring the amount of oxygen babies breathe in versus carbon dioxide they breathe out, researchers can estimate how many calories they are burning. If the body is working harder to burn calories, it produces more carbon dioxide.

Recent Comments