McKinsey & Co., the global consulting giant, agreed to pay nearly $600 million last week to settle allegations by 49 states that its work for large opioid manufacturers helped “turbocharge” sales of the drugs, contributing to an addiction epidemic that rocked the country and has caused more than 400,000 deaths.

The settlement is a black eye for the firm, which holds itself out as the preeminent global consultant advising corporations and governments. But because most of the money to be paid by McKinsey will go to state programs funding addiction treatment centers and recovery services, the deal may allow a McKinsey hedge fund affiliate to generate investment gains, an NBC News investigation has found. That’s because the firm’s wholly owned hedge fund affiliate, called MIO Partners, holds indirect stakes in addiction treatment centers and a maker of overdose treatment products.

In addition, investment records show, during the years McKinsey was helping opioid makers propel sales of the drugs, MIO Partners held stakes in companies that profited from increased usage.

The MIO investment records don’t provide enough detail to determine how much it has made or stands to make from opioid-related investments. But they show that MIO, which is run on behalf of current and former McKinsey employees, invested in companies that benefited during the rise of the opioid crisis and now holds stakes in companies that could profit from remediation efforts in the aftermath.

A McKinsey spokesman said it is “false and absurd” to suggest that the firm will benefit financially from the big state settlement. “McKinsey has no visibility into or control of how settlement money will be used by the states,” he said. In addition, he said, the hedge fund and the firm’s consulting business are “operationally separate,” and the firm’s past stakes in opioid makers through MIO were taken by outside investment managers whose decisions McKinsey doesn’t direct or control.

But Marianne Jennings, a professor of legal and ethical studies in business at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, said the simultaneous operation of the hedge fund and McKinsey’s vast consulting business poses potential conflicts that aren’t easily remedied.

“On conflicts of interest, there are two ways to handle them — you disclose them and manage it or you don’t do it,” Jennings said. “I don’t know how you manage that unless you can show me there is absolute isolation of this fund. No matter how you slice it, you benefit. I don’t see how you don’t have an interest in that and input in that.”

MIO Partners oversees its investments with a staff and a 14-person board, regulatory filings show. Eight current or former McKinsey executives are directors, joined by six non-McKinsey directors, four of whom joined recently.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

MIO’s management selects an array of investment managers to deploy its $14.6 billion. They make investment choices independent of MIO and are compensated by McKinsey, according to an independent study commissioned by the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, a federal watchdog that monitors the island’s budget. After MIO selects its investment managers, it may discuss individual investments with them, the study said.

McKinsey says the MIO structure is “not unusual.” But it is. Most large companies, including all the major consulting firms, hire third-party firms like Fidelity and Vanguard to oversee their employees’ retirement accounts. Those firms typically offer employees a handful of big-name mutual funds to choose from, letting them make their own investment decisions. The holdings of such mutual funds are transparent, while MIO’s stakes are more opaque.

Since 2010, Labor Department filings show, a retirement fund managed by MIO has amassed a $108 million stake in Deerfield Management Co., a $10 billion health care investment firm based in New York. Two top Deerfield executives previously worked at McKinsey.

During the years McKinsey’s hedge fund has invested with Deerfield, the firm has taken large stakes in opioid manufacturers, in distributors of the drugs and in addiction treatment facilities. In 2018, Deerfield’s many holdings throughout the sector led an anti-opioids group to label its strategy “a vertical integration of human misery.”

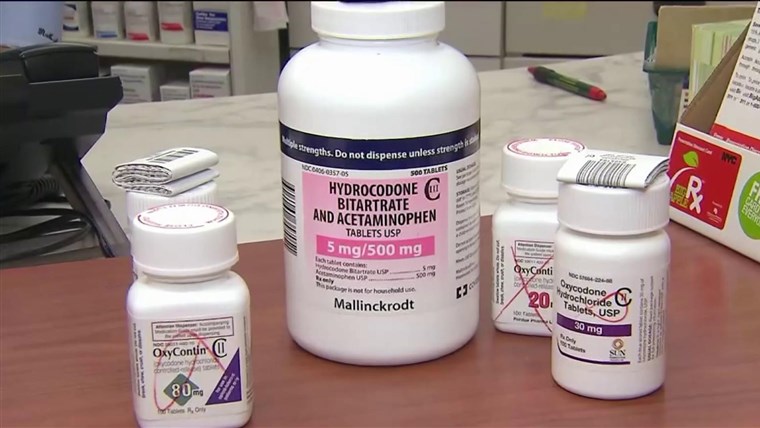

In 2017, for example, Deerfield was a 6 percent shareholder in Mallinckrodt, a major opioid maker that filed for bankruptcy protection last year after it faced enormous legal liabilities for the role critics accused it of playing in the crisis. From 2011 through 2016, Deerfield held a stake — at one point valued at $90 million — in Teva Pharmaceuticals, an opioid maker and defendant in national opioid litigation that it settled with plaintiffs, denying the allegations, in 2019. Deerfield also took stakes in two distribution companies ensnared in government-led opioid litigation: McKesson and Cardinal Health. Both companies have denied wrongdoing.

Deerfield didn’t respond to an email seeking comment about its investments in the opioid industry; the phone number listed on its website has been “deactivated.”

In 2017, Deerfield Management agreed to pay $4.7 million to settle charges by the Securities and Exchange Commission that it had profited in trades while failing to prevent its employees from misusing material, nonpublic information. The agency alleged that Deerfield had received nonpublic information about coming policy changes at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and generated over $700,000 in profits. Deerfield neither admitted nor denied the allegations.

Adamis Pharmaceuticals, a company that develops products to treat opioid overdoses, may also benefit from opioid settlement funds. According to an SEC filing from last summer, MIO owned 26 percent of the company’s preferred shares; the stake was purchased through an outside investment manager.

The McKinsey spokesman reiterated that its third-party managers make their choices independently of MIO.

‘Counter the emotional messages’

Investigators in Massachusetts last year released internal emails and other documents detailing McKinsey’s role in helping push the sale of opioids as a consultant for Purdue Pharmaceuticals, the maker of OxyContin. McKinsey worked with Purdue for 15 years, starting in 2004, the states said. Last year, Purdue pleaded guilty to three felonies as a result of conduct spanning a decade — 2007 to 2017 — while it was working side by side with McKinsey. Purdue agreed to pay $8.3 billion.

Investigators said McKinsey designed Purdue’s marketing schemes, including a plan to “turbocharge” OxyContin sales at the height of the opioid epidemic. McKinsey also advised Purdue to maximize its OxyContin profits by focusing on higher, more lucrative doses and scheduling more visits by Purdue sales representatives to high-volume opioid prescribers. McKinsey encouraged Purdue to get opioid manufacturers to band together to “defend against strict treatment” by the Food and Drug Administration and worked with the company on ways to “counter the emotional messages from mothers with teenagers that overdosed in OxyContin,” Massachusetts filings show.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey said of the settlement, “Our communities will receive substantial resources for treatment, prevention, and recovery services, and families who have seen their loved ones hurt and killed by the opioid epidemic will have the truth exposed about McKinsey’s illegal and dangerous partnership with Purdue Pharma.”

McKinsey said it believes its past opioid work was “lawful.” It said it agreed to the settlement “without finding or admission of wrongdoing or liability of any kind.”

Money from the settlement will create the Massachusetts Opioid Recovery and Remediation Fund “to expand access to opioid use disorder prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery options,” according to the state.

Recovery Centers of America, an addiction treatment company in which Deerfield Management invested $331 million in 2015 and 2016, operates addiction treatment facilities in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and other states that were part of the McKinsey settlement.

Kevin Sneader, McKinsey’s global managing partner, said that in striking the settlement, “we chose to resolve this matter in order to provide fast, meaningful support to communities across the United States.”

“We deeply regret that we did not adequately acknowledge the tragic consequences of the epidemic unfolding in our communities,” he said. “With this agreement, we hope to be part of the solution to the opioid crisis in the U.S.”

McKinsey’s hedge fund has come under scrutiny before. In 2018, The Wall Street Journal reported that the hedge fund held investment stakes in companies it had advised in bankruptcy proceedings. The proceedings require advisers to be unconflicted in their work, and rules bar them from having stakes in cases’ outcomes. In 2019, McKinsey paid $15 million to settle an inquiry by a unit of the Justice Department into whether it violated disclosure rules designed to prevent conflicts of interest in corporate bankruptcies.

And the 2019 study commissioned by Puerto Rico financial oversight board noted that MIO investments in that bankruptcy case “could be perceived as a conflict.”

Recent Comments