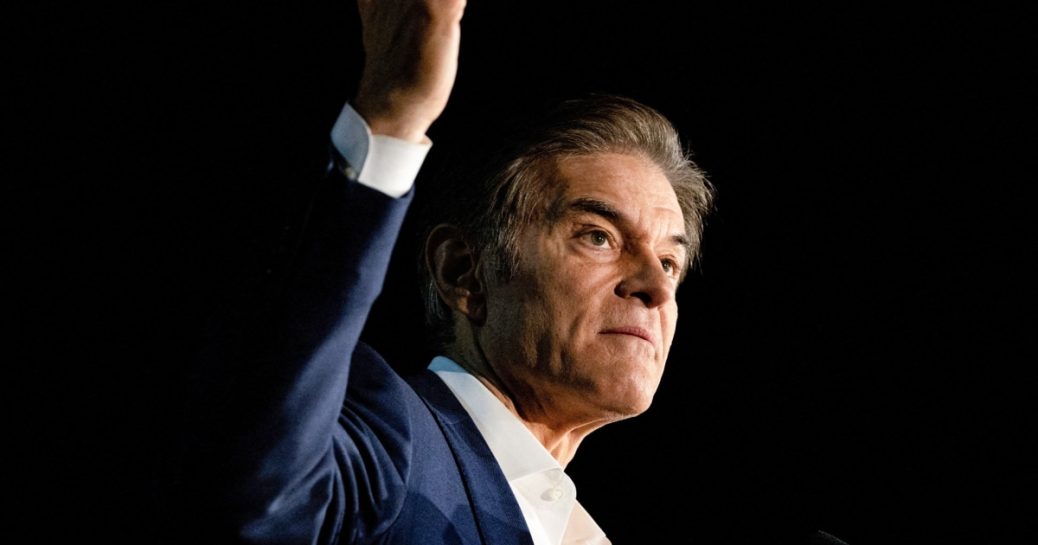

It was a surprising pick among many surprising picks. This week, President-elect Donald Trump announced his choice to head the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Dr. Mehmet Oz, who is as famous for the “America’s Doctor” moniker as he is for the number of dubious health claims he’s made from that perch over the years.

Perhaps it shouldn’t have been surprising. After all, Trump endorsed Oz in his unsuccessful Senate bid in 2022, and in 2016 Trump appeared on Oz’s show to undergo a “surreal” on-air physical in lieu of sharing his medical records with the public. Plus, Melania Trump likes him.

Currently on his website, he calls himself global adviser and stakeholder for the online supplement and wellness retailer brand iHerb; his Instagram page also links out to the iHerb shop. That may not be the case for long.

“Under federal law, he would be prohibited from making decisions that could impact his financial interests,” said Kedric Payne, vice president, general counsel and senior director of ethics for the nonprofit, nonpartisan government watchdog group Campaign Legal Center. “So that means that, as head of CMS, he would have to divest of those interests if he’s making decisions that are related to it.”

In another important way, Oz’s selection is also a downright puzzling choice to Dr. Richard Besser, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and former acting director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This position traditionally has had someone with deep experience in health insurance and health policy to run very complex programs,” Besser said. CMS provides health care for more than 100 million Americans, including lower-income people and people with disabilities. “Dr. Oz has a career as a surgeon and a television doctor. His approach on television has been one that has really focused on the role of the individual in their health — and the person in this role is really required to make sure that our government is meeting the needs of our entire country.”

For that matter, many of those individual actions Oz recommended on his TV show over the years were based on questionable scientific evidence, Besser said. In a BMJ study from 2014, for instance, researchers evaluated health claims made on 40 randomly selected episodes of “The Dr. Oz Show,” a syndicated daytime TV show that ran from 2009 to 2022. They found that about half of the recommendations made on the show were unsupported by scientific evidence.

Oz’s team did not respond to a request for comment. Trump’s transition team argued in favor of Oz’s qualifications. “He is an eminent Physician, Heart Surgeon, Inventor, and World-Class Communicator, who has been at the forefront of healthy living for decades,” Karoline Leavitt, Trump-Vance transition spokeswoman, said in a statement. “Dr. Oz has many accomplishments, and he will do great work in President Trump’s second administration to make America healthy again.”

In his own defense, Oz argued in a 2015 exclusive interview with NBC News that his television program was “not a medical show.” He also denied any conflicts of interest and said he had not sold any products “off the show.” He also said that he would refrain from using words like “miracle,” and even added that “there are segments that I made that I wish I could take back.”

But it’s hard to take back an idea once it’s been widely publicized on television. Here are eight health claims — with little or no scientific evidence to back them up — that Oz made over the years.

Green coffee extract, the ‘magic weight loss cure’

In 2014, Oz went to Washington to seek help fighting internet marketers who were using his name and image to sell weight loss products. Instead, senators suggested that he was part of the problem, subsequently grilling him on the many diet supplements he’d promoted on his show.

“When you feature a product on your show, it creates what has become known as the ‘Dr. Oz Effect’ — dramatically boosting sales and driving scam artists to pop up overnight using false and deceptive ads to sell questionable products,” then-Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., said to Oz at the Senate hearing.

Senators provided several examples from Oz’s own show, but much of the hearing focused on his claims about green coffee bean extract.

“You may think magic is make believe, but this little bean has scientists saying they found the magic weight loss cure for every body type. … This miracle pill can burn fat fast,” Oz said in a 2012 episode.

“I don’t get why you need to say this stuff because you know it’s not true,” McCaskill said. “So why when you have this amazing megaphone and this amazing ability to communicate, why would you cheapen your show?”

Oz replied: “I actually do personally believe in the items that I talk about on the show; I passionately study them. I recognize that oftentimes they don’t have the scientific muster to present as fact.”

Later that year, a company selling the green coffee extract touted by Oz paid the Federal Trade Commission $3.5 million in a settlement over a complaint that it had “used the results of a flawed study to make baseless weight-loss claims” to retailers, according to the FTC. Also that year, a pair of researchers retracted their study supposedly showing that the green coffee bean pills led to weight loss. “The sponsors of the study cannot assure the validity of the data so we, Joe Vinson and Bryan Burnham, are retracting the paper,” read a statement that appeared on the website for the open-access scientific journal that had published the paper. The retraction was first reported by Retraction Watch.

By October 2014, The Washington Post reported that Oz’s website had been “scrubbed of almost every mention” of green coffee bean extract; the episode had also been taken down from YouTube, citing a “copyright claim” by way of explanation.

Supplements and ‘the holy grail of cancer prevention’

Oz’s claims about green coffee extract got major headlines, but it’s not the only weight loss supplement he touted on his show. He once said that raspberry ketone was “the No. 1 miracle in a bottle to burn your fat,” and in a 2013 episode, he called Garcinia cambogia “the simple solution you’ve been looking for to bust your body fat for good,” according to Vox.

Writing for Science-Based Medicine, Dr. Harriet Hall conceded that Garcinia cambogia “may have a role in helping patients lose weight by assisting motivation and enlisting placebo effects,” but the data at that point didn’t show a “clinically relevant advantage” over old-fashioned diet and exercise.

The BMJ study from 2014 found that the majority of Oz’s health recommendations touched on nutrition and dietary advice. In a 2011 episode, he said human chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone produced during pregnancy, could result in weight loss when combined with a diet restricted to 500 calories a day. (The research shows no evidence that HCG is an effective weight loss tool.)

According to The Washington Post, in a 2012 episode, Oz touted the cancer-preventing benefits of selenium, a mineral found in soil that is responsible for, among other things, protecting the body against the damage caused by severe viral infection, according to the National Institutes of Health.

There is research to suggest that people who have a selenium deficiency — which is very rare in the U.S. — may have an increased risk of developing certain cancers, including colon, rectum, prostate, lung, bladder, skin, esophagus and stomach, according to the NIH; however, it is “not clear” whether selenium supplements reduce cancer risk. Furthermore, selenium supplements can interfere with other medications, and too much of the mineral is linked to health risks. “Extremely high intakes of selenium can cause severe problems, including difficulty breathing, tremors, kidney failure, heart attacks, and heart failure,” the NIH states.

In a 2011 episode, Oz suggested to his audience that endive, red onion and sea bass are anti-cancer foods that could reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by up to 75%.

Three years later, the journal Nutrition and Cancer revisited those claims in a 2014 paper titled “Reality check: no such thing as a miracle food.” The authors noted, for example, that while kaempferol — a flavonoid found in endive — had demonstrated cancer inhibition in lab studies, it was unclear whether those findings would translate to people consuming endive in “usual dietary quantities.” They warned their peers to “be cognizant of the public health messages that are taken from their individual studies.”

Apple juice and arsenic

Oz suggested in a 2011 episode that apple juice contained unsafe levels of arsenic, citing tests from a New Jersey lab. The Food and Drug Administration performed its own tests and found “no evidence of any public health risk from drinking these juices.”

The FDA further said that Oz failed to note whether he was referring to organic or inorganic arsenic — a crucial point, as organic arsenic is not likely to cause harm, while the inorganic can potentially be dangerous. In response, a spokesman for “The Dr. Oz Show” at the time, Tim Sullivan, told CBS News, “We don’t think the show is irresponsible.”

Sullivan said, “We think the public has a right to know what’s in their foods. The position of the show is that the total arsenic needs to be lower.”

A Consumer Reports study published several months later did find that some juice samples had high levels of arsenic, most of which, the study said, was inorganic.

Lavender soap for restless leg syndrome

“I know this sounds crazy, but people put it under their sheets,” Oz said in a 2010 episode of his show, according to Business Insider. “We think the lavender is relaxing and may be itself beneficial.”

A comparatively innocuous claim, to be sure, but nonetheless, the suggestion that placing a bar of lavender soap under the bedsheets can help ease restless leg syndrome is a dubious one, and it was debunked by “Life’s Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience.

Recent Comments