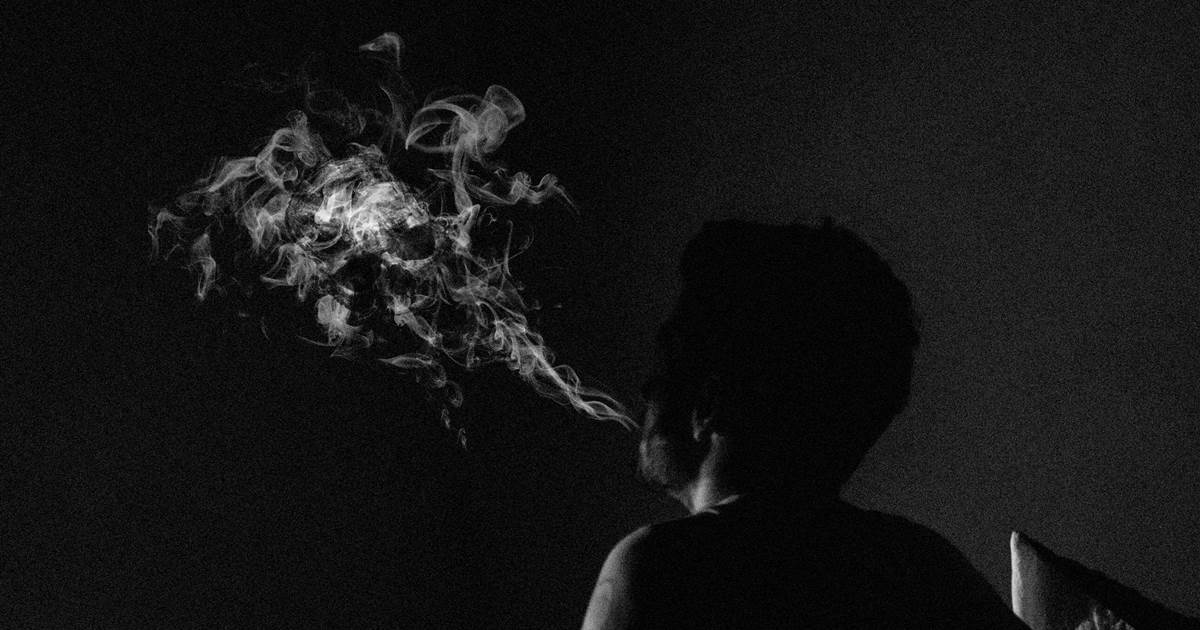

“Do you want to be a 50-year-old meth addict?”

For Roger, the enormity of what he had lost during his nearly two decades of off-and-on methamphetamine use — and what more he had to lose — hit home hard when a man he was dating asked him that question.

Roger, who was 47 at the time, had already suffered a major ischemic stroke thanks to meth, the powerfully addictive stimulant that had long since taken over his life.

So when Roger, who is from Dallas and asked that his last name not be published for fear that meth’s stigma could hurt his career, heard that a study was looking for people like him to test a treatment for meth use disorder, he jumped at the chance.

“I woke up one day and I had no cravings,” Roger, now 50, recalled of the life-altering change he experienced only weeks into the clinical trial.

Just as the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or NIDA, has issued a report detailing the U.S.’s soaring rate of overdose deaths tied to meth, a national research team has reached a milestone by developing what its recent double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial has established is the first safe and efficacious medication-based treatment for addiction to the often ruinous stimulant.

While the treatment’s success rate, 14 percent, is modest and important questions remain about its potential for real-world use, the study’s publication in The New England Journal of Medicine last month has nevertheless raised hope in the addiction field that more research might build on its findings. In particular, investigators hope the benefits of the treatment’s two-drug combination of daily bupropion (the antidepressant Wellbutrin) and injections every three weeks of naltrexone (which is used to treat both alcohol and opioid use disorder) could be magnified if it is paired with evidence-based psychosocial support, like cognitive behavioral therapy.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Madhukar Trivedi, a psychiatrist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, described meth addiction as “a very severe illness that affects the person’s health, employment, quality of life, their marriage, self-worth — and it is fatal.”

“For those people who benefit from this treatment, it is very likely to have a positive impact for their lives, as well as societally,” Trivedi said.

Methadone and buprenorphine have long been used to treat opioid use disorder — albeit woefully underused. But when it comes to treating people whose neural reward circuits have been hijacked by meth, there is no comparable approved prescription therapy. That gaping hole in addiction medicine has left the country especially unprepared to deal with a blooming crisis of meth use that, as the opioid epidemic hogs focus and funding, has blindsided small towns and rural communities in particular.

‘The next drug epidemic’

The estimated national population of people with meth use disorder increased by more than 45 percent from 2016 to 2018, from 684,000 to over 1 million, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NIDA researchers estimated in a letter published in JAMA Psychiatry last month that from 2012 to 2018, the national meth-related overdose death rate rose nearly fivefold.

“We have got to find something to help these folks, because meth is becoming the next drug epidemic,” said Dr. Michael Mancino, a psychiatrist and addiction specialist at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Once beaten back by major government efforts to clamp down on domestic meth lab production in the mid-2000s, the national meth scourge is surging today, driven by cheap imports funneling in from Mexico, the Drug Enforcement Administration has determined. NIDA’s director, Dr. Nora D. Volkow, said a substantial portion of meth’s growing use appears to be among people who also use drugs like heroin or fentanyl, who may look to stimulant drugs, a category that includes cocaine, to balance out opioids’ depressive effects, or who may take them when they cannot get access to opioids.

“It’s a major problem making the opioid crisis much more lethal than it was before,” Volkow said of the convergence of the drug epidemics.

In 2019, about 16,000 of the more than 70,000 estimated overdose deaths in the U.S. involved meth, and about half of those deaths also included opioids as a factor, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national drug crisis has only worsened during the coronavirus pandemic. Research published in JAMA in September documented a spike after the first wave of government shutdowns in the use of meth, cocaine, fentanyl and heroin among those diagnosed with or at risk of substance use disorders.

Meth and the gay community

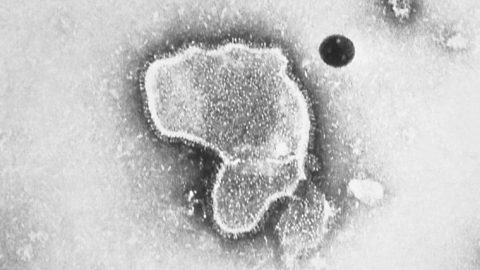

Meth has cast a heavy cloud over the gay community in particular for decades. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated that in 2015, past-year meth use prevalence was more than four times higher among gay men compared to straight men — at 4.1 percent versus 0.9 percent. Research has found that the drug is closely linked to sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men and that it has been a major driver of HIV transmission among this population.

In November, researchers at the City University of New York published findings in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome from an ongoing study of nearly 5,000 sexual and gender minorities who have sex with men and who are considered at risk of HIV infection. The study’s authors found that participants’ odds of contracting the virus during the study were four times higher among those reporting recent meth use and seven times higher among those reporting persistent use of the drug.

Research also suggests that for people who are living with HIV, like Roger, meth exacerbates the virus’s harm to the body.

Roger, who said he first started taking meth at gay “circuit” parties, said his use of the drug led him to stop going to the doctor and quit taking his HIV treatment a decade ago. His immune health plummeted, and even though he has been back on antiretrovirals since 2014, his T-cell count still has not quite risen back into the fully healthy range.

‘A tremendous signal of hope’

The new meth treatment study was funded by the NIDA, a division of the National Institutes of Health, and conducted in the clinical trials network the institute oversees. The study, which was conducted from 2017 to 2019, enrolled 403 adults who had used meth on at least 18 of the previous 30 days and expressed a wish to cut back or quit.

The study’s authors defined the regimen as effective if at least three-quarters of a participant’s urine screens for meth were negative during the last two weeks of each six-week phase of the trial.

To buttress adherence to the daily pill regimen, the participants were paid $3 every time they logged in to a video app and recorded themselves taking their daily bupropion. The study co-authors said in interviews that the method was likely to have been a driver of the study’s success, considering that previous studies reported lower bupropion adherence, and it could prove challenging to replicate in real-world practice.

Overall, 13.6 percent of the treatment group met the definition of a response, compared with 2.5 percent of the placebo group.

“I had a pipe in the house, I had meth in the house, and after two weeks I was not even looking at it,” Roger recalled of how well the treatment worked for him. “I’d been a daily user for years and years and years.”

Trivedi called the findings “very definitive” and emphasized that the treatment increased success fivefold.

Mancino was more tempered in his assessment, saying, “It’s certainly a start, but the important thing is that we don’t jump to conclusions and say, ‘Oh, here’s the answer.'”

Linda Dwoskin, a professor of pharmaceutical education at the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy who is researching a novel compound meant to mitigate meth-taking and -seeking behaviors, called the results a “tremendous signal of hope” to families who have been devastated by loved ones’ use of the drug.

Trivedi hopes that a future study including people who use meth less than daily would yield a greater benefit. For now, Volkow said, the goal is to work with the Food and Drug Administration to design a trial that would seek to replicate the recent study’s results while providing the FDA with the data to consider approving the bupropion-naltrexone regimen for meth use disorder.

Dr. W. Brooks Gentry, chief medical officer of InterveXion Therapeutics in Little Rock, Arkansas, who is researching a monoclonal antibody designed to bind to meth and blunt its effects, praised the study’s finding that the treatment was also associated with an overall reduction in the percentage of positive meth urine samples.

In addition, those who received bupropion and naltrexone reported fewer meth cravings and improvements in their quality of life.

“If you can get any kind of reduction and you can get people’s lives to improve, that’s got to be viewed as success,” Gentry said.

Jessica Hulsey, founder and CEO of Addiction Policy Forum, a nonprofit that advocates for people with substance use disorders and their families, said the study sends a powerful message to researchers and pharmaceutical companies that “this is an area where medication development is possible.”

Trivedi and his colleagues speculated that bupropion, which acts on the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine, may have cushioned the emotional and neurological blow of meth withdrawal. And in theory, naltrexone reduced the euphoric effects of and cravings for meth.

However, Dr. Melissa Zook, a family and addiction physician in London, Kentucky, said the use of naltrexone would be problematic in her practice, because it cannot be combined with buprenorphine. All her patients who report taking meth also use opioids, and they have a strong preference for buprenorphine over naltrexone to treat opioid use disorder, so treating patients for both substance use disorders would present a contraindication.

In addition, the new study could not determine how the bupropion-naltrexone regimen might benefit people over terms longer than just six to 12 weeks.

But three years after the trial, Roger has been on a health kick, having gone vegetarian and gotten a trainer. While he is still taking the bupropion, last summer he stopped the naltrexone his doctor had prescribed to him off label once the study ended.

“Meth,” Roger said, “is not part of my plan.”

Recent Comments