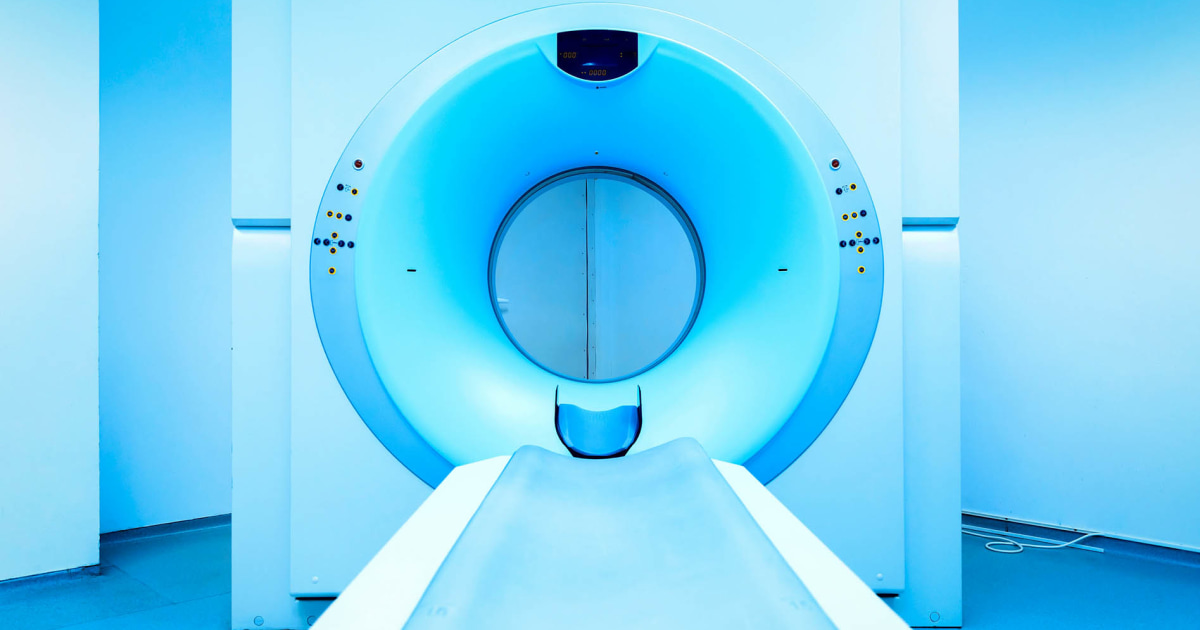

Rebecca Smith-Bindman, a professor at the University of California-San Francisco medical school, has spent well over a decade researching the disquieting risk that one of modern medicine’s most valuable tools, computerized tomography scans, can sometimes cause cancer.

Smith-Bindman and like-minded colleagues have long pushed for federal policies aimed at improving safety for patients undergoing CT scans. Under new Medicare regulations effective this year, hospitals and imaging centers must start collecting and sharing more information about the radiation their scanners emit.

About 93 million CT scans are performed every year in the United States, according to IMV, a medical market research company that tracks imaging. More than half of those scans are for people 60 and older. Yet there is scant regulation of radiation levels as the machines scan organs and structures inside bodies. Dosages are erratic, varying widely from one clinic to another, and are too often unnecessarily high, Smith-Bindman and other critics say.

“It’s unfathomable,” Smith-Bindman said. “We keep doing more and more CTs, and the doses keep going up.”

One CT scan can expose a patient to 10 or 15 times as much radiation as another, Smith-Bindman said. “There is very large variation,” she said, “and the doses vary by an order of magnitude — tenfold, not 10% different — for patients seen for the same clinical problem.” In outlier institutions, the variation is even higher, according to research she and a team of international collaborators have published.

She and other researchers estimated in 2009 that high doses could be responsible for 2% of cancers. Ongoing research shows it’s probably higher, since far more scans are performed today.

The cancer risk from CT scans for any individual patient is very low, although it rises for patients who have numerous scans throughout their lives. Radiologists don’t want to scare off patients who can benefit from imaging, which plays a crucial role in identifying life-threatening conditions like cancers and aneurysms and guides doctors through complicated procedures.

But the new data collection rules from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued in the closing months of the Biden administration are aimed at making imaging safer. They also require a more careful assessment of the dosing, quality, and necessity of CT scans.

The requirements, rolled out in January, are being phased in over about three years for hospitals, outpatient settings, and physicians. Under the complicated reporting system, not every radiologist or health care setting is required to comply immediately. Providers could face financial penalties under Medicare if they don’t comply, though those will be phased in, too, starting in 2027.

When the Biden administration issued the new guidelines, a CMS spokesperson said in an email that excessive and unnecessary radiation exposure was a health risk that could be addressed through measurement and feedback to hospitals and physicians. The agency at the time declined to make an official available for an interview. The Trump administration did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

The Leapfrog Group, an organization that tracks hospital safety, welcomed the new rules. “Radiation exposure is a very serious patient safety issue, so we commend CMS for focusing on CT scans,” said Leah Binder, the group’s president and CEO. Leapfrog has set standards for pediatric exposure to imaging radiation, “and we find significant variation among hospitals,” Binder added.

CMS contracted with UCSF in 2019 to research solutions aimed at encouraging better measurement and assessment of CTs, leading to the development of the agency’s new approach.

The American College of Radiology and three other associations involved in medical imaging, however, objected to the draft CMS rules when they were under review, arguing in written comments in 2023 that they were excessively cumbersome, would burden providers, and could add to the cost of scans. The group was also concerned, at that time, that health providers would have to use a single, proprietary tech tool for gathering the dosing and any related scan data.

The single company in question, Alara Imaging, supplies free software that radiologists and radiology programs need to comply with the new regulations. The promise to keep it free is included in the company’s copyright. Smith-Bindman is a co-founder of Alara Imaging, and UCSF also has a stake in the company, which is developing other health tech products unrelated to the CMS imaging rule that it does plan to commercialize.

But the landscape has recently changed. ACR said in a statement from Judy Burleson, ACR vice president for quality management programs, that CMS is allowing in other vendors — and that ACR itself is “in discussion with Alara” on the data collection and submission. In addition, a company called Medisolv, which works on health care quality, said at least one client is working with another vendor, Imalogix, on the CT dose data.

Several dozen health quality and safety organizations — including some national leaders in patient safety, like the Institute of Healthcare Improvement — have supported CMS’ efforts.

Concerns about CT dosing are long-standing. A landmark study published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 2009 by a research team that included experts from the National Cancer Institute, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and universities estimated that CT scans were responsible for 29,000 excess cancer cases a year in the United States, about 2% of all cases diagnosed annually.

But the number of CT scans kept climbing. By 2016, it was estimated at 74 million, up 20% in a decade, though radiologists say dosages of radiation per scan have declined. Some researchers have noted that U.S. doctors order far more imaging than physicians in other developed countries, arguing some of it is wasteful and dangerous.

More recent studies, some looking at pediatric patients and some drawing on radiation exposure data from survivors of the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, have also identified CT scan risk.

Older people may face greater cancer risks because of imaging they had earlier in life. And scientists have emphasized the need to be particularly careful with children, who may be more vulnerable to radiation exposure while young and face the consequences of cumulative exposure as they age.

Max Wintermark, a neuroradiologist at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who has been involved in the field’s work on appropriate utilization of imaging, said doctors generally follow dosing protocols for CT scans. In addition, the technology is improving; he expects artificial intelligence to soon help doctors determine optimal imaging use and dosing, delivering “the minimum amount of radiation dose to get us to the diagnosis that we’re trying to reach.”

But he said he welcomes the new CMS regulations.

“I think the measures will help accelerate the transition towards always lower and lower doses,” he said. “They are helpful.”

Recent Comments