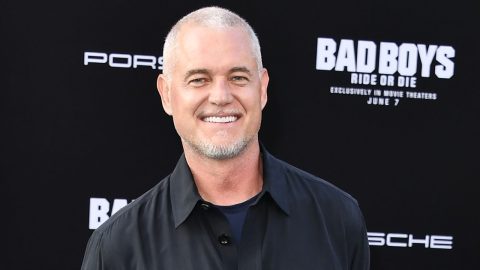

Chris Buckner was in his car, racing to try to get to his son, Dylan, before the 18-year-old killed himself.

It was just after 3 p.m. on Jan. 7, and friends had alerted Dylan’s parents that he might be in danger.

Karen Buckner, Dylan’s mother, checked the location services on her son’s phone. The phone placed him at a hotel a few miles away from their Northbrook, Illinois, home. Chris headed to the hotel, texting and calling Dylan along the way and getting no response.

“Just please let him still be alive,” Chris said he thought over and over during the drive.

Dylan was a high school senior with a promising future. A star quarterback, he had a 4.7 grade point average and 14 offers to play football at Division III schools. His number one choice was MIT.

If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text TALK to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

But in recent months, depression that had started creeping up on Dylan a couple years ago had worsened, as the places where he once thrived closed due to the coronavirus pandemic: his high school classrooms, where he excelled in honors and Advanced Placement courses; the football field, where he was a team captain; and clubs, like the school newspaper, where he was a sports editor.

As Chris neared the hotel that afternoon, he saw a swarm of police cars.

Immediately, he knew: He had arrived too late to save Dylan.

Across the country, signs are emerging of a mental health crisis among youths. While there is no data at this point that conclusively links teen suicides to remote schooling or any other byproduct of the pandemic, grieving parents and mental health experts have a message for anyone struggling: Help is available.

“Suicide is not a desire to die. It is a desire to end intense emotional pain. It is a problem that they truly believe is unsolvable,” said Susan Tellone, clinical director of Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide. “We really need to help our children see that we can, together, help solve this problem that seems unsolvable to them.”

“Suicide is not a desire to die. It is a desire to end intense emotional pain.”

The pandemic turned Dylan’s structured life of school and team workouts upside down. Activities he did in his spare time, such as mentoring students with special needs, also vanished.

Still, his suicide that day stunned everyone, including classmates who had seen him in their remote class an hour earlier, his mother said.

“Everybody was in shock. They said, ‘I just saw him, he was in my 2 o’clock class on Zoom,’” Karen said.

“But it was on Zoom,” she added. “I believe things would have been different if he was sitting in class with 25 kids.”

A complex problem with no single cause

One night over the summer, when Dylan would have normally been enjoying football camp had the coronavirus not canceled it, Karen heard him pounding on the punching bag in their basement. When she went downstairs, Dylan, who rarely cried, had tears in his eyes.

“It was very, very hard for him to even say a word,” she said. Finally, Dylan confided that he had been feeling really down.

It was clear he needed help. The Buckners got Dylan a psychiatrist right away. He started taking antidepressants.

Dylan had not shared with his parents until then that he had felt depressed for some time. He said it had become dramatically worse in recent months, and it continued to get worse before it got better: In September, he attempted suicide. He went to in-patient treatment for a week, then continued therapy.

But in the weeks leading up to his death, the depression had seemed to wane, making it all the more mystifying to his parents why Dylan killed himself. His father feels his brain chemistry predisposed him to depression; the pandemic on top of that proved deadly, he believes.

“Had Covid not happened, or our country’s response to Covid been better, I think Dylan would still be here,” Chris said. “Covid’s not just killing people by the disease. It’s killing people by depression and suicide, and God knows what else.”

Other parents whose children have taken their own lives over the past year — including a 16-year-old in Maine, a 12-year-old in Texas and a 13-year-old in Washington — have also blamed the pandemic.

Mental health experts say suicides are complex and occur due to a combination of factors rather than a single reason. They have not definitively tied the pandemic to suicides — especially because when schools across the country closed, certain teenagers initially fared better.

“Kids that might have been suicidal before the pandemic because of bullying in school, or anxiety about FOMO, like ‘all my friends are doing this thing,’ all of that’s gone,” said Jonathan Singer, president of the American Association of Suicidology and an associate professor of social work at Loyola University Chicago, using an abbreviation for fear of missing out.

There was also less academic pressure at first, Singer added, with many schools promising not to flunk students last spring.

But nearly a year in, grades count again in a lot of schools that still haven’t reopened, and students who flourished from interactions with peers and praise from teachers are having a hard time emulating that from behind a computer screen.

“I think we need to be worried,” said John MacPhee, executive director and CEO of The Jed Foundation, a nonprofit that partners with schools to strengthen their mental health support programs.

“For teens, one of the key things that’s being interrupted now is the need to socialize.”

“For teens, one of the key things that’s being interrupted now is the need to socialize,” he said. “They’re wired to be with other people, to be separating their identity from their parents. It’s very, very important for their identity, and this pandemic has really interrupted and insulted that.”

Even before the pandemic, suicide was the second-leading cause of death among high schoolers, with the national suicide rate for individuals ages 10 to 24 increasing 57.4 percent between 2007 and 2018.

National data for 2020 suicides is not yet available, but there are other concerning indicators.

From March to October, the proportion of mental health-related emergency department visits spiked 31 percent for adolescents ages 12 to 17 compared to the same time frame in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The fear that isolation could contribute to mental health problems has prompted some districts to take action: In Nevada, the Clark County school district recently decided it will reopen after a spate of student suicides.

Experts say a rise in youth suicides during the pandemic can be prevented. They encourage parents and other adults to look for warning signs, such as increased irritability in their children, sudden changes in their behavior or appearance, and comments such as “I’m a burden” or “I’m creating stress for this family,” Tellone said.

Having a single trusted adult in their lives is also protective against suicide, and may not necessarily be a parent. It may be a coach, a teacher, or a bus driver — sources of support that are harder to access if schools are closed. Still, many districts are working to implement mental health services virtually, from programs that alert school administrators to searches for self-harm on school-issued computers to training teachers to recognize signs of distress over Zoom.

“It’s important to train them and understand that they are the front line, almost by themselves, so they really know what to do if they see behaviors or changes in a student that causes them concern,” MacPhee said.

‘Improve the moment’ and other tips for moments of crisis

Dylan woke up in good spirits on his final day of life, his father said.

In the morning, he had gotten excused from class to go to a promising appointment with another psychiatrist — a doctor Dylan had found as he searched for different treatments for depression. Both he and his mom felt encouraged when the appointment ended around 9:45 a.m.

After the appointment, he signed onto his remote high school classes and took an AP physics test. He caught up with one of his football coaches over Zoom at lunch. He then signed onto the rest of his classes for the day, and by 3 p.m., Karen said, a switch had apparently flipped — where Dylan felt like “there was nothing that can dig me out of this hole.”

Suicide, especially in adolescents, can often be the result of impulses, experts say — a feeling that they cannot overcome a moment of intense pain, with fewer life experiences than adults have to show that they can be resilient.

But suicide is not an inevitable outcome, even in those instances. Those who have survived being suicidal urge anyone who has considered hurting themselves to have a detailed plan for how they will persevere through tough moments.

Imadé, 33, a communications professional and a mental health advocate in North Carolina, who asked that she be identified only by her first name to protect her privacy, started experiencing panic attacks and depression in eighth grade. By age 30, she had attempted suicide multiple times. After learning tips for coping with depression through dialectical behavior therapy, she now helps others through the nonprofit she founded, Depressed While Black, which donates Black-affirming personal care items to psychiatric patients and helps members of the Black community connect with Black therapists.

Listening to her favorite artist and weightlifting saved Imadé’s life. Other tips she recommends include breathing meditations; using crisis text lines; using the notOK app, which was created by teenagers to help people when they are feeling vulnerable; contacting your therapist, if you have one; calling suicide prevention hotlines, which are free and available to anyone; and doing things such as dunking your head in cold water or squeezing an ice cube as a distraction from your feelings.

“You have to find ways to slow that train down so you can get to the other side,” Imadé said, referring to a strategy known as “improve the moment.”

“Make sure that you have a backup to a backup.”

The important thing, she added, is to “make sure that you have a backup to a backup” plan for how to avoid self-harm.

“Even if you’re like, ‘this tool didn’t help me, I still feel terrible,’ it still gives you time to distance yourself from the suicidal thoughts,” she said.

‘Don’t be ashamed’

As Dylan’s parents mourn their son, they are hoping speaking out will save other teens. They fear Dylan may have hidden how bad he was feeling so he didn’t upset them.

“The message I’m trying to share with everybody is, if kids or anybody else is struggling, don’t be ashamed of it. It’s not unlike having cancer or a broken leg,” Chris said. “You wouldn’t expect to get better without telling your parents and seeing a doctor and taking medication.”

Karen, who used to take walks after dinner with Dylan, now goes on nightly strolls with his teammates and friends. They talk about how they are doing. They talk about what they will miss about Dylan.

Karen said she will miss his smile, and the conversations she used to have with him, and his kindness.

When asked what he will miss the most about his son, Dylan’s father paused.

“I’ll just miss everything,” Chris said, his voice breaking. “He was the best person in my world. I’ll just miss everything.”

Recent Comments