Registered nurse Luis Medina walked into his shift in December and was told a positive Covid-19 patient was resisting wearing his oxygen mask. Despite repeated attempts by a fellow nurse, they said, it was hard to communicate with the patient, because he spoke Spanish.

Medina, 25, who works at a community hospital near La Mirada, California, went to see the patient and explained in his native language the importance of wearing the mask and the consequences of not doing so.

“Just having that language barrier and being able to address that, the patient ended up getting better, because he kept the oxygen mask on,” said Medina, a graduate of and part-time professor at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Los Angeles.

Yet the past year has been particularly difficult, as he had been a nurse for less than a year when the coronavirus pandemic hit. Medina was used to seeing patients leave the hospital shortly after they arrived. With Covid-19, he wasn’t so sure the majority of his mostly Latino patients would be leaving that quickly.

The pandemic has disproportionately hit Latinos throughout the country, who are already at a disadvantage as they are likely to work in front-line jobs and have the highest uninsured rates. Liz Guevara, 31, a nurse care manager at La Clinica del Pueblo in Washington, D.C., saw a majority of Latino patients during the pandemic, and she found knowing Spanish and being Latina to be a big help; the Washington area has a large Central American population.

“We need to be culturally competent. Just because a provider may speak Spanish doesn’t mean the patient will be comfortable to talk about their pain,” she said. “Patients are more reluctant to speak to a provider if they can’t fully express themselves.”

Beyond language, it’s about understanding different customs and cultures — and some of the difficulties many families go through. Guevara, who came to the U.S. at age 6, said her parents struggled to get access to health care, which motivated her to study health care disparities, including the lack of Latino providers. The realization led her to a career in public health nursing. As someone who lacked a mentor while entering the field, she is passionate about the impact Latinos can make in the profession, whether it’s through mentorship or programs.

How the numbers look

A nursing degree can provide ample career opportunities, from a trauma nurse to a newborn nursery nurse with a median salary of $75,330, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Yet the number of Latino nurses is disproportionate to its demographic’s size. Nearly 1 in 5 people in the country are Hispanic, according to the recent census, but the Department of Health and Human Services found in a 2017 analysis that out of all 3.3 million registered nurses, only 5.7 percent were Latinos; 73.5 percent were white.

That’s better than it was when Antonia Villarruel, the dean of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania, first started — then, it was just 2 percent — but there is still a long road ahead for improvement.

Villarruel has said for years that structural barriers get in the way of getting more Latinos into nursing. Education is the first barrier, and it goes beyond a high school diploma. High schools with predominantly Latino student bodies are in underserved communities, Villarruel said, and students aren’t getting the science courses they need to enter nursing.

“So if you don’t come from a good high school, get good science grades, it’s not easy,” she said. “There’s barriers almost in every single junction that you move forward in.”

Adrianna Nava of Chicago, president of the National Association of Hispanic Nurses, or NAHN, said obstacles that affect the number of Latino nurses include a lack of access to finances to pay for their educations and a lock of mentors to help them navigate the profession. Some immigrants may be navigating questions about status as they try to seek an education.

Nava, who leads over 1,700 NAHN members while running a hospital quality department, said Latino nurses play an important role in ensuring that more Hispanics get quality health care — which was especially significant during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“We also bring with us that lens of how do we decrease health disparities so that way we can improve care and make sure that patients are not being treated differently because of their ethnicity or race,” she said.

Villarruel, who grew up in a Mexican household in Detroit and now heads a nursing school that has been ranked as the world’s best — tells all her Latino students about the importance of Spanish fluency, as patients will assume they can speak it. Like Nava, she said it goes beyond language.

“It helps set up that relationship — familiarity and acceptance — that is so important when people are confronted with illness,” she said.

Expose young people early to what it takes

To create opportunities for Latinos interested in going into nursing, it’s important to understand the multiple paths to go into the profession, experts said.

The most common route to become a registered nurse involves graduating with a bachelor of science degree in nursing at an accredited nursing program, followed by two years of advanced nursing, clinical training and successful completion of NCLEX-RN, a standardized test needed to become a registered nurse. The degree process can take three to four years, and it’s possible to receive associate degrees through community colleges, but bachelor’s degrees are in higher demand.

There are faster paths, such as accelerated nursing programs, like Penn’s Accelerated BSN Second Degree Admissions, which can take 12 to 18 months and is meant for students who earned bachelor’s degrees in other subjects. Yet with undergraduate prerequisites and the science courses required for nursing schools — which are competitive — getting to the finish line can be challenging.

That’s why being aware of options at a young age is critical. High school counselors play a large role in encouraging students to consider nursing before they enter college, Villarruel said. Colleges can also take an active role in reaching out to high schools that have Latino students, fostering relationships with them and even having alumni help.

College education is expensive, but Villarruel said options to keep students from being dissuaded from pursuing nursing are to attend community colleges to cut costs and to apply to schools with good financial aid. Depending on the school, an accepted student might not have to take out loans.

To address the shortage of Latinas specifically, Hispanic Star and NurseHeroes.org collaborated to create a scholarship program, Hispanic Star Nurse Heroes, to create opportunities in the health care industry. The fund includes a $150,000 donation that will give 20 future nurses $7,500 apiece to cover tuition. The goal will be to raise $7.5 million for 1,000 Latinas, and, because 92 percent of nurses are women, the fund expects applicants to be women but makes it clear that the program is open to all Latinos.

“Latinas make excellent nurses — yet the pathway to a career in nursing can be challenging, as many Latinas continue to work while going to school,” Nava said in a statement. “A scholarship would really lessen the financial burden so Latinas could focus academically on their career.”

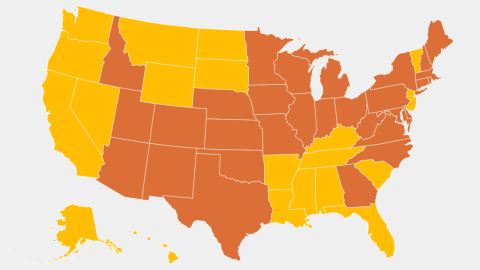

Other opportunities include NAHN’s partnership with the University of Alabama, which focuses on preparing 80 Latino associate degree registered nurses to get bachelor of science degrees in nursing through their college programs. Using a $1.7 million grant over four years, the BAMA-Latino Project, which is meant for nurses who have full-time jobs, is available for residents of selected states. Additional resources include the College Health Scholars Program created by the National Hispanic Medical Association, which provides Hispanic college students with academic, professional and financial aid resources to enter the health care workforce.

Nava said colleges should make concentrated efforts to hire faculty members who are racially and ethnically diverse. Representation matters, she said, and the barriers to get into academia are visible; less than 5 percent of full-time professors at postsecondary institutions in 2018 were Latinos.

Latino nurses have played an important role during the pandemic, Villarruel said, working in their communities and encouraging people to get tested and vaccinated. They’ve also been there to answer questions for Covid-19 patients who have had to be isolated with restrictions on visitors. She said she thinks about her Mexican father, who wouldn’t have felt comfortable speaking English.

“If you were there and didn’t have somebody who spoke your same language or knew how important it was for you to connect with your family, that just increases the isolation that’s there,” Villarruel said. “Having to be in a place where he would have to fend for himself — super frightening.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Recent Comments