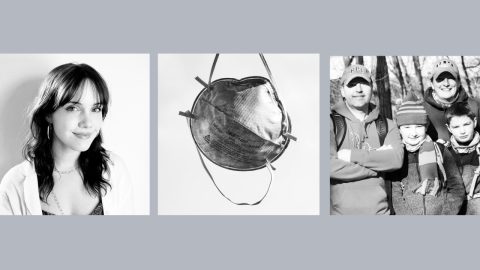

Tony Christon-Walker was determined to set up an HIV prevention clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, that would succeed where others have long struggled to combat the scourge of the virus among his fellow queer Black men.

The director of prevention and community partnerships at the nonprofit AIDS Alabama, he spent much of 2019 hiring a clinic staff composed of people of color. They were trained to provide the kind of affirming care that, he said, “reflects our culture,” and that would encourage local men at risk of HIV to keep coming back.

Even facing the headwinds of the Covid-19 pandemic, the fledgling clinic, which specializes in prescribing the HIV prevention pill known as PrEP, for pre-exposure prophylaxis, made steady progress in realizing his vision.

But now clinics like this that provide vital HIV prevention services to disadvantaged populations are facing a dire — and for some of these nonprofit groups, even existential — financial crisis driven by the vagaries of an arcane federal law governing prescription drug discounts.

These safety net clinics are set to lose well over $100 million in annual HIV prevention funds due in part to a recent decision by the pharmaceutical giant Gilead Sciences to cut off what has become an increasingly valuable revenue stream supporting these organizations in their grassroots efforts to prevent the virus’s spread. The consequences are expected to be most devastating to clinics in the South, due to the region’s disproportionately large uninsured population and the fact that half of HIV transmissions in the United States occur in those states.

The imminent funding loss threatens to substantially compromise an ambitious plan the federal government launched last year to end the nation’s HIV epidemic by 2030. People of color will likely bear the brunt of the impact — at a time when the public health sector is striving to mitigate racial disparities, not see them worsen.

“This will shut us down,” said Christon-Walker, of how Gilead’s policy change will affect AIDS Alabama’s PrEP clinic. Losing the funds, he said, will “destroy our program and totally inhibit our ability to see uninsured clients, which make up the bulk of our business.”

Dependence on a ‘patchwork solution’

The financial morass centers around a 1992 federal drug pricing law called 340B. The law grants clinics that care for a disproportionate number of uninsured and low-income individuals the right to purchase pharmaceuticals at steep discounts through their in-house or contracted pharmacies. Public and private insurers typically reimburse 340B-designated clinics’ pharmacies at a dollar amount close to a prescribed drug’s list price; and in a unique setup that Gilead recently decided to end, citing ballooning costs, the California-based company has long engaged in a similar reimbursement process when providing free antiretrovirals for HIV treatment or prevention to uninsured people. Such transactions yield surplus cash — known as the “340B spread” — that these organizations spend on their services.

For expensive brand-name drugs, the 340B spread can be quite a substantial sum. By contrast, when these clinics prescribe a cheaper generic medication, the difference between the price they pay and the price at which they are reimbursed is often relatively minimal; so the prescription generates little revenue.

Consequently, even as the Biden administration seeks to drive down the cost of pharmaceuticals, the little-publicized 340B pricing law conversely — and perversely — causes many health care facilities serving low-income individuals to depend on drug prices for all kinds of health conditions remaining high to support their bottom lines.

Tim Horn, director of health care access at the HIV advocacy group NASTAD, said the 340B funding system is a “patchwork solution” to the woeful lack of investment in the nation’s medical and public health safety net, and one that amounts to “a house of cards.”

Because of the high price of antiretrovirals used to treat and prevent HIV, the 340B spread funnels hundreds of millions of dollars annually into HIV-focused safety net clinics that serve the low-income, uninsured and nonwhite populations that are disproportionately impacted by the virus. The additional funds allow these clinics to provide extra services, such as transportation assistance or case management.

In the coming years, high-quality HIV treatment regimens will increasingly go off patent. This is good news for the nation’s overall health care bill, and state Medicaid budgets in particular. But as cheaper generic antiretrovirals enter the market, safety net clinics treating people with HIV will sustain a progressive and potentially devastating loss of their 340B revenue.

Currently, however, the most pressing 340B-related financial concern in the national HIV arena revolves around revenue tied to the historically pricey PrEP.

The Food and Drug Administration approved Gilead’s antiretroviral Truvada for use as HIV prevention in 2012. PrEP’s popularity has soared in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that about 285,000 people — overwhelmingly white gay and bisexual men — were taking it by 2019. The federal agency credits PrEP with helping drive the modest 8 percent decrease, from 37,800 to 34,800 cases, in estimated annual HIV transmissions in the U.S. between 2015 and 2019.

But PrEP’s use has remained disappointingly limited among Black and Latino men who have sex with men, who comprised a respective 25 percent and 21 percent of the 36,800 new HIV diagnoses in 2019, according to the CDC. These are disparities that 340B clinics have worked hard, and are uniquely positioned, to address.

In recent years, the activist group PrEP4All has campaigned against Truvada’s high price, which Gilead has raised from $1,160 per month in 2012 to $1,842 today. The activists have claimed that Truvada’s cost has been the predominant factor limiting PrEP access in the nation — a claim echoed by Dr. Rochelle Walensky, now the CDC director, during a May 2019 congressional hearing held over Gilead’s high list price for PrEP.

And yet, PrEP is widely covered by insurance, with federal guidelines requiring that almost all private plans, as well as state Medicaid programs expanded under the Affordable Care Act, cover it with no cost-sharing. Gilead also provides free PrEP to uninsured people.

Moreover, the high price of Truvada, and now also Descovy — an updated version of Truvada that the FDA approved as the second available form of PrEP in 2019 — has actually been a financial godsend to the 340B clinics that serve the very populations among whom HIV transmission is the highest.

According to Horn, the 340B spread for a single prescription for Truvada or Descovy amounts to about $1,200 to $1,600 monthly, or $14,400 to $19,200 annually. Clinics have been able to use this windfall to subsidize for their uninsured PrEP patients the quarterly clinic visits and laboratory tests that are required to maintain the prescription and that are not covered by Gilead’s patient assistance program.

Such funds have also been channeled into paying 340B clinics’ facility and technology costs and to pay for patient navigators, safe sex counselors, outreach workers, condoms, advertising, patient transportation, sexually transmitted infection screening and treatment, and opioid use disorder treatment. And in some cases, this money covers other medications for uninsured people, including the initial few months of HIV treatment before the federal Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program kicks in and picks up the tab.

Now, much of the 340B spread tied to PrEP is poised to vanish, potentially hobbling the services that help keep the HIV epidemic in check. Many uninsured people are expected to lose access to PrEP because of an inability to pay for their clinic visits and lab tests.

“It’s going to put a lot of our programs in serious harm’s way at best,” Jim Pickett, senior director of prevention advocacy and gay men’s health at AIDS Foundation Chicago said. “Some of them will be decimated and destroyed.”

HIV advocates worry that this funding crisis will only exacerbate the racial disparities that have long characterized the nation’s epidemic.

“HIV has a disproportionate impact on Black and brown communities, especially here in Texas. I really fear that we will have more Black and Latinx people acquiring HIV if other funding sources aren’t in place,” Christopher Hamilton, CEO of Texas Health Action, an HIV- and LGBTQ-focused nonprofit health care provider, said as he echoed a concern shared among his colleagues across the country.

A ‘peculiar’ and ‘unsustainable’ system

After Gilead announced in early April that it would change its patient assistance program reimbursement policy starting in October, an outcry followed, prompting the company to move the cut-off to January 2022.

Also in April, multiple generic versions of Truvada entered the market for the first time. Some have a list price as low as $30 per month, posing a major threat to Gilead’s highly profitable PrEP sales.

This price plunge heralds a second oncoming financial crisis for 340B organizations. Insurers are already starting to push people with PrEP prescriptions off of Descovy or the brand-name Truvada and onto the cheap generic drug. Should this shift persist, 340B revenue tied to insured people receiving PrEP will steadily deplete.

Determining how much money is at stake with the 340B spread tied to PrEP — even Gilead says it does not know the true sum — largely requires querying each clinic individually. The Health Resources and Services Administration recently ascertained from 195 health centers splitting a $54 million HIV-prevention grant from the agency that in 2020, these clinics prescribed PrEP to 63,000 people — up from 20,000 the previous year. According to the agency, which had no comment for this article, 96 percent of these centers participate in the 340B program. And while it is unknown what percentage of these PrEP recipients are uninsured, overall about a quarter of HRSA-funded health centers’ patients lack health insurance.

NBC News asked nearly 120 HIV prevention-focused 340B clinics for their PrEP-patient figures. The vast majority were unresponsive or refused to share their data. Many said they were wary of alienating Gilead, given the clinics’ further dependency on charitable grants from the company, which is the dominant manufacturer of HIV-treatment pharmaceuticals.

Nevertheless, NBC News was able to tally that at the very least, some 7,000 uninsured 340B clinic patients nationwide are receiving free PrEP from Gilead’s patient assistance program monthly. This modest figure alone translates to a pending minimum loss in 340B-spread revenue to such clinics of $100 million annually starting in January. Given the low response rate to queries — data on roughly 3,000 of these patients came from publicly available information concerning California, and the remainder came from just 24 clinics elsewhere — and given the implication of the HRSA figures, the true dollar figure is likely considerably higher.

“It is peculiar that all of these organizations have been able to get all this funding for receiving a free drug,” said Carl Schmid, executive director at HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. “But that’s the system that we have been living with, and people have been counting on that for years.”

During an April 8 call between HIV advocates and Gilead to discuss the impending financial changes, Eric Leue, vice president of prevention services at the HIV-prevention clinic Friends for Life in Memphis, Tennessee, was clearly distraught as he pleaded with company representatives to reconsider their change in policy. Noting that Memphis has one of the nation’s highest HIV diagnosis rates, Leue said, Gilead’s “unconscionable” impending reimbursement cut will force his clinic to close, and that overall, it “will set this county and our population back by at least another decade.”

Coy Stout, vice president of market access strategy at Gilead, explained in an interview that the company never intended to establish the 340B revenue stream in question. In 2004, eight years before PrEP was even approved, Gilead made a fateful decision regarding the administration of its patient assistance program. Instead of having a single contracted mail-order pharmacy send free antiretrovirals to uninsured people directly, as pharma companies typically do, Gilead decided it would reimburse the nation’s pharmacies for purchasing the company’s HIV antiretrovirals and hepatitis B antivirals. According to Stout, the intention was to make filling prescriptions convenient for uninsured patients.

Gilead did not expect pharmacies to purchase substantial quantities of the company’s antiretrovirals at 340B discount prices, because the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program covers HIV treatment for the uninsured and underinsured.

But the U.S. government would establish no such safety net program to pay for PrEP.

So particularly in the 13 states that have not expanded Medicaid, which are concentrated in the South, there are now substantial — and ever growing — numbers of uninsured people receiving free PrEP from Gilead’s patient assistance program through 340B clinics.

As for insured people receiving PrEP at 340B clinics, responses from the 24 clinics pointed to some 2,850 such individuals receiving brand-name Truvada and 5,900 receiving Descovy. These figures, which experts believe represent vast underestimates of actual national totals, translate to at least $125 million in annual 340B revenue that stands to diminish given insurers’ efforts to push patients onto cheap generic versions.

To put the cumulative pending loss of 340B-spread funds into context, the federal government funded the “Ending the HIV Epidemic” plan by increasing the HIV-related budget by $267 million in 2020 and by $405 million in 2021. The Biden administration’s 2022 budget request has sought to raise this additional outlay to $670 million.

HIV policy advocates like Schmid have been pushing Congress, the Health Resources and Services Administration and the CDC for increased funding to address the lost revenue tied to PrEP’s 340B spread. The CDC traditionally forbids clinics from spending agency grant money to pay for the lab tests and clinic visits for uninsured people on PrEP. However, it does allow Ending the HIV Epidemic-related grants to cover such costs.

From Gilead’s perspective, its patient assistance program is well over budget and, according to Stout, is “unsustainable.” He further stressed that the company is not able simply to turn around and donate the lost 340B spread to the impacted clinics. Under federal tax law, charitable contributions on Gilead’s part cannot be directly geared around their own commercial products.

“It makes good business sense for Gilead to change the policy,”NASTAD’s Tim Horn said, “but it’s just very, very unfortunate timing.”

Recent Comments