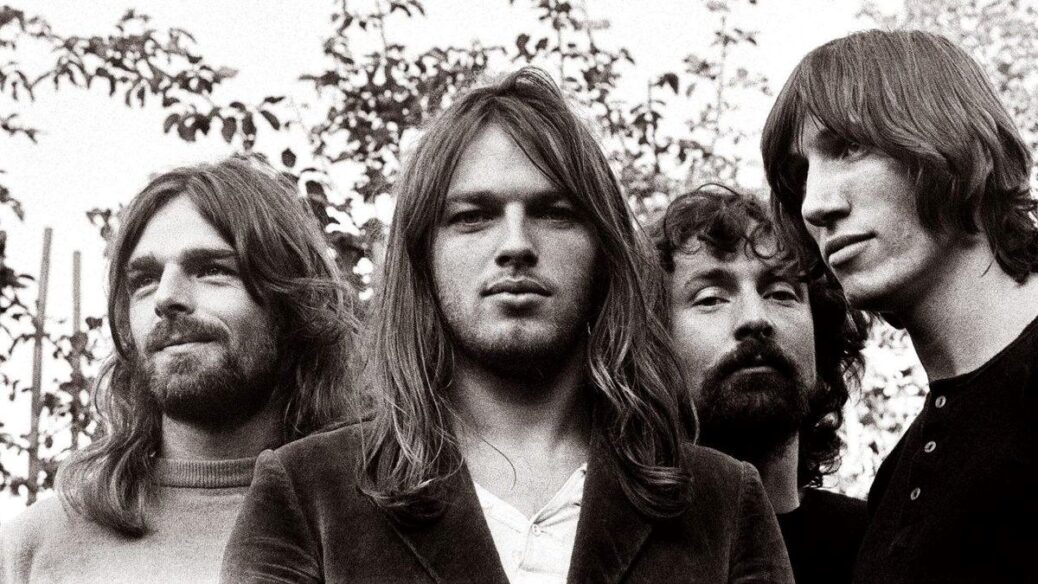

There’s little left that needs to be said about Pink Floyd’s astronomical run in the 1970s. Undeniably, the creative, commercial, and critical prosperity achieved by their final four LPs of the decade — The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975), Animals (1977), and The Wall (1979) — have rarely, if ever, been matched by any other rock band. Likewise, their musical and cultural influence were just as expansive and enduring, so it’s no wonder they remain almost as prevalent and adored today. (Of course, their output in the 1980s and beyond is also worthwhile, but those ’70s LPs are easily their most significant.)

However, the process of getting to that point was far from quick or easy, as their earliest years were filled with crises of artistic identity and potential. Due mostly to the tragic departure of initial mastermind Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd struggled to find their niche; thus, they mixed and matched respectable and cherished — yet also polarizing and unconfident — hodgepodges of psychedelia, classical, and avant-garde until finally nailing their capabilities with Dark Side… While every member was crucial to fully realizing that potential, it was Barrett’s replacement, guitarist-vocalist David Gilmour, who really steered Pink Floyd toward the start of their iconic legacy.

Like many English bands of the time, the group was formed by schoolmates and associates. Suffice it to say that bassist Roger Waters, drummer Nick Mason, and keyboardist Richard Wright were there from the start; by 1964, Waters’ childhood friend, Syd Barrett, joined, too, and the following year he became their frontman and principal songwriter. Throughout the mid-’60s, they (as The Tea Set) performed Merseybeat and R&B music at notable local venues; all the while, they sought ways to enhance their sets with lengthy solos, trippy lighting theatrics, psychedelic sounds, and other soon-to-be trademark extravagances.

Along the way, Barrett learned of another ensemble called The Tea Set, so he drew inspiration from blues icons Pink Anderson and Floyd Council and changed their name to The Pink Floyd Sound. Shortly thereafter, they simply became Pink Floyd, focused on idiosyncratic Barrett originals, and signed to EMI. By August 1967, they’d released their psychedelic landmark debut, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, which sold well and was championed by prominent publications like Record Mirror and NME for its impact on the genre.

Just as they started truly making a name for themselves, however, Barrett began excessively using LSD and succumbing to depression. His behavior became more disruptive and unpredictable as the year continued, with him either zoning out, detuning his guitar, or doing something equally troublesome during concerts and television appearances. By December 1967, his irreconcilable issues led to the rest of the band finding only one solution: bring on a fifth member — David Gilmour — to compensate for Barrett on stage.

Editors’ Picks

Meanwhile, Gilmour — who’d previously busked around France with Barrett — was playing with rock quintet Jokers Wild. Naturally, he left to join Pink Floyd, with the public announcement being made in January 1968 and the original plan being that Gilmour would play shows while Barrett stayed at home and wrote songs. This dynamic was doomed from the start, though, and by the end of the month, the other four members regrettably decided that Barrett needed to be gone for good. By April 1968, Pink Floyd were officially a quartet again, eager to focus on a more professional and productive future. There was just one problem: the absence of Barrett meant the absence of a lead singer and songwriter, so the remaining foursome were left at a bit of a crossroads.

(I’d be remiss not to mention that they still cared deeply about Barrett, as is evident not only in Barrett’s lingering influence on their music, but also in the fact that Gilmour, Waters, and Wright contributed to one or both of his two solo albums: 1970’s The Madcap Laughs and Barrett. As Waters famously declared, “He was our friend, but most of the time we now wanted to strangle him.”)

Luckily, Gilmour immediately established himself as a confident and capable equal part of the group. Beyond taking over for Barrett during shows, he sang on almost half of the songs on their sophomore sequence, A Saucerful of Secrets (which features Barrett’s last song, “Jugband Blues”). True, Wright and Waters were the main writers here, and the LP suffered from less critical praise and more investigational wackiness (to put it nicely); yet, Gilmour’s distinctively warm and earnest voice and guitarwork instantly became an invaluable part of Pink Floyd’s identity. He even had a hand in penning the lengthy and immensely popular title track, explaining: “I tried to add what I knew of harmony and bring it slightly more mainstream … We passed on all our individual desires, talents and knowledge to each other.”

With 1969’s More — their third LP, used as the soundtrack for Barbet Schroeder’s film of the same name — Gilmour took on an even larger role by handling all lead vocals. Right away (via opener “Cirrus Minor”), his matter-of-fact delivery points to later gems like “Echoes”, “Wish You Were Here”, and “Learning to Fly”. Later, the almost proto-punk “The Nile Song”; the softly acoustic “Crying Song” and “Green Is the Colour”; the robust meditation “Cymbaline”; and Side Two’s 20-plus-minute suite strike a superb balance between the space rock voyages of More’s siblings and the economical, poignant, and advanced songwriting of later material. Again, Gilmour didn’t have much to do with the writing of this stuff, but his voice and musicianship are vital to their prophetic triumph, and his ability to flesh it all out on stage was already a key component of Pink Floyd’s burgeoning new persona.

Editors’ Picks

Admittedly, double album follow-up Ummagumma deserves to be their most polarizing album from this period due to the wildly experimental nature of its second half. Basically, each member has about 20 minutes devoted to their own content, resulting in contributions both classically eccentric (Wright’s “Sysyphus” and Mason’s “The Grand Vizier’s Garden Party”) and nightmarishly avant-garde (Waters’ “Several Species of Small Furry Animals”). However, it’s Gilmour’s three-part “The Narrow Way” that is most significant and, frankly, enjoyable because of its medley of sunnily acoustic instrumentation, hallucinogenic deviations, and sinister dissonance. In that way, his piece is likely the most suggestive of their future classics. (Conversely, the first half of Ummagumma consists of four live cuts that received majorly positive feedback in otherwise critical reviews, and Gilmour’s presence on them was — unsurprisingly — a big reason why.)

Despite still being divisively weird and meandering in spots, 1970’s Atom Heart Mother points further to what was to come. Namely, the orchestral and eponymous opening epic (which Gilmour aptly likened to the “theme from an imaginary western”) frequently sees Gilmour’s matchless six-string style govern the rest of the bombastically bizarre arrangement; similarly, the dreamily dynamic and Beatles-esque “Fat Old Sun” — written and sung by him — captures Pink Floyd’s revered knack for light build-ups into explosive catharses (like on “Comfortably Numb”).

Both the music and overarching reception of those collections are understandably mixed, as the quartet were still trying to find their footing and their audience. In contrast, 1971’s Meddle (which Gilmour dominates as a writer and performer) is where it all came together artistically and critically. For instance, starter “One of These Days” is immensely unconventional and peculiar, but it’s also highly focused and poised, with inventive guitarwork sown throughout. Then, the nuanced, captivating, and chic one-two punch of “A Pillow of Winds” and “Fearless” demonstrate a clear advancement in songwriting, instrumentation, and even production. Furthermore, the Waters-led “San Tropez” is surprisingly playful, while the penultimate “Seamus” is an enjoyably arid and bluesy romp.

Of course, it all serves as an appetizer to the 23-minute closing track, “Echoes”, which might as well be nicknamed “Dark Side Jr.” for how much it foreshadows their 1973 masterpiece (plus everything that came afterward). For one thing, Waters and Gilmour share lead vocals, and the suite’s immaculate compromise between tastefully adventurous musicianship, adventurous sound effects, and moving melodies (even if they overtly resemble The Beatles’ “Across the Universe”) make for their greatest composition thus far. As for 1972’s more eclectic and less cohesive Obscured by Clouds (another movie soundtrack), it was a clear final steppingstone thanks to the proggy moodiness and/or eccentricity of the title track, “Childhood’s End”, “Burning Bridges”, and “Mudmen”. The rest, as they say, is history.

It’s impossible not to lovingly speculate what Pink Floyd might’ve become had Syd Barrett remained; likewise, there’s no refuting the importance of Mason, Wright, and especially Waters (as their main conceptualist) in their eventually esteemed trajectory. That said, Gilmour was undisputedly the key to them becoming what they did, as he was always a central and beneficial player in their tangents and triumphs. No matter how aimless or accessible their earliest works were, Gilmour’s matchlessly endearing, sophisticated, and resourceful contributions guaranteed that he paved the way for their success.

In fact, you could say that he shone brightest of all.

Recent Comments