People at the highest levels of power in China appreciate the importance of cyber capabilities. The CEO of Qihoo 360, the country’s biggest cybersecurity company, famously criticized Chinese researchers doing work outside the country and implored them to “stay in China” to realize the “strategic value” of powerful software vulnerabilities used in cyber-espionage campaigns. Within months, his company was linked to a hacking campaign against the country’s Uyghur minority.

A wave of stricter regulations followed, tightening the government’s control of the cybersecurity sector and prioritizing the state’s security and intelligence agencies over all else—including the companies whose software is insecure.

“The Chinese have a unique system reflecting the party-state’s authoritarian model,” says Dakota Cary, an analyst at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

Chinese cyber researchers are effectively banned from attending international hacking events and competitions, tournaments they once dominated. A hacking contest pits some of the world’s best security researchers against one another in a race to find and exploit powerful vulnerabilities in the world’s most popular tech, like iPhones, Teslas, or even the kind of human-machine interfaces that help run modern factories. Prizes worth hundreds of thousands of dollars incentivize people to identify security flaws so that they can be fixed.

Now, however, if Chinese researchers want to go to international competitions, they require approval, which is rarely granted. And they must submit everything to government authorities beforehand—including any knowledge of software vulnerabilities they might be planning to exploit. No one other country exerts such tight control over such a vast and talented class of security researchers.

This mandate was expanded with regulation requiring all software security vulnerabilities to be reported to the government first, giving Chinese officials unparalleled early knowledge that can be used for defensive or offensive hacking operations.

“All of the vulnerability research goes through an equities process where the Chinese government gets right of first refusal,” says Adam Meyers, senior vice president of intelligence at the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike. “They get to choose what they’ll do with this, really increasing the visibility they have into the research being conducted and their ability to find utility in all of it.”

We’ve seen one exception to this rule: an employee of the Chinese cloud computing giant Alibaba reported the famous Log4j vulnerability to developers at Apache instead of first delivering it to Chinese government authorities. The result was a public punishment of Alibaba and implicit warning for anyone else thinking of making a similar move.

China’s stricter policies have an impact well outside the country itself.

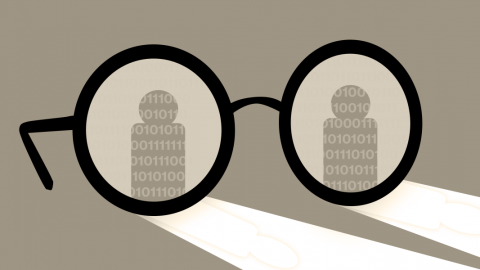

Over the last decade, the “bug bounty” model has provided millions of dollars to build a global ecosystem of researchers who find software security vulnerabilities and are paid to report them. Multiple American companies host marketplaces where any tech firm can put its own products up for close examination in exchange for bounties to the researchers.

By any measurement, China ranks at or near the top in alerting American firms to vulnerabilities in their software. In his congressional testimony last week, Cary said an unnamed large American firm had disclosed to him that Chinese researchers received $4 million in 2021. The American companies benefit from the participation of these Chinese researchers. When the researchers report a bug, the companies can fix it. That’s been the status quo since the bounty programs began booming in popularity a decade ago.

However, as the Chinese government tightens control, this multimillion-dollar ecosystem is now delivering a steady stream of software vulnerabilities to Chinese authorities—effectively funded by the companies and at no cost to Beijing.

“China’s policy that researchers must submit vulnerabilities to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology creates an incredibly valuable pipeline of software capabilities for the state,” says Cary. “The policy effectively bought at least $4 million worth of research for free.”

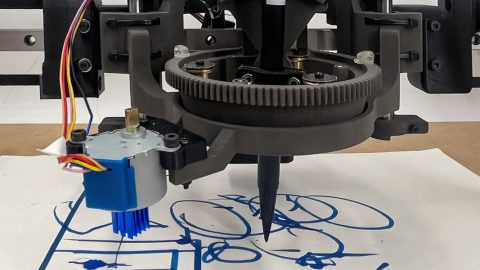

Robot Hacking Games

In 2016, a powerful machine called Mayhem won the Cyber Grand Challenge, a cybersecurity competition held by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Mayhem, which belongs to a Pittsburgh company called ForAllSecure, won by automatically detecting, patching, and exploiting software security vulnerabilities. The Pentagon is now using the technology in all military branches. Both the defensive and offensive possibilities were immediately obvious to everyone watching—including Chinese officials.

DARPA hasn’t run a similar program since 2016. China, on the other hand, has put on at least seven “Robot Hacking Games” competitions since 2017, according to Cary’s research. Chinese academic, military, and private-sector teams have all been drawn to competitions overseen by the Chinese military. Official documents tie automated discovery of software vulnerabilities directly to China’s national goals.

As the Robot Hacking Games were beginning, the CEO of Qihoo 360 said automated vulnerability discovery tools were an “assassin’s mace” for China.

“Whoever masters the automatic vulnerability mining technology will have the first opportunity to attack and defend the network,” he said. Claiming that his own company had developed “a fully autonomous automatic vulnerability mining system,” he argued that the technology is the “‘killer’ of network security.”

The Robot Hacking Games are one example of the way Chinese officials at the highest level have been able to see an American success and then smartly make it their own.

“Time and again, China has studied the US system, copied its best attributes, and in many cases expanded the scope and reach,” says Cary.

As the US-China rivalry continues to function as the defining geopolitical relationship of the 21st century, cyber will play an outsize role in what China’s leaders rightfully call a “new era.” It touches everything from commercial competition to technological advancement and even warfare.

In that new era, Xi’s stated goal is to make China a “cyber superpower.” By any measure, he’s done it.

Recent Comments