Tal, who has been obsessed with infectious disease since losing an uncle to HIV/AIDS and a cousin to meningococcal meningitis, wondered what this striking diversity could reveal about our immune response to infection. According to one hypothesis, the wide array of these receptors is the result of an evolutionary arms race between disease-causing microbes and the immune system. Think of the receptor as a lock, and the “Nothing to see here” message as a key. Pathogens might evolve to produce their own chemical mimics of this key, effectively hiding from the immune system in plain sight. In response, the human population has developed a wide range of locks to frustrate any given impostor key.

Wanting to test this hypothesis, Tal found herself walking the halls of Stanford, asking colleagues, “Who’s got a cool bug?” Someone gave her Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Previous research from Tal’s collaborator Jenifer Coburn, a microbiologist now at the Medical College of Wisconsin, had established that Lyme bacteria sport a special protein crucial for establishing a lasting infection. Knock this protein out, and the immune system swiftly overwhelms the bugs. The big question, however, was what made this protein so essential. So Tal used what’s known as a high-affinity probe as bait—and caught the Borrelia’s mimic of our “Don’t eat me” signal binding to it. In other words, she confirmed that the bacteria’s sneakyprotein was, as predicted, a close match for a healthy cell’s signal.

Sex differences in Lyme infection

Until then, Tal says, she had never given Lyme disease much thought. But the more she learned, the more disturbed she grew. Even after timely antibiotic treatment, roughly 10% of all Lyme patients go on to develop chronic symptoms that can include crushing pain, debilitating fatigue, and cognitive changes that make basic tasks a struggle.

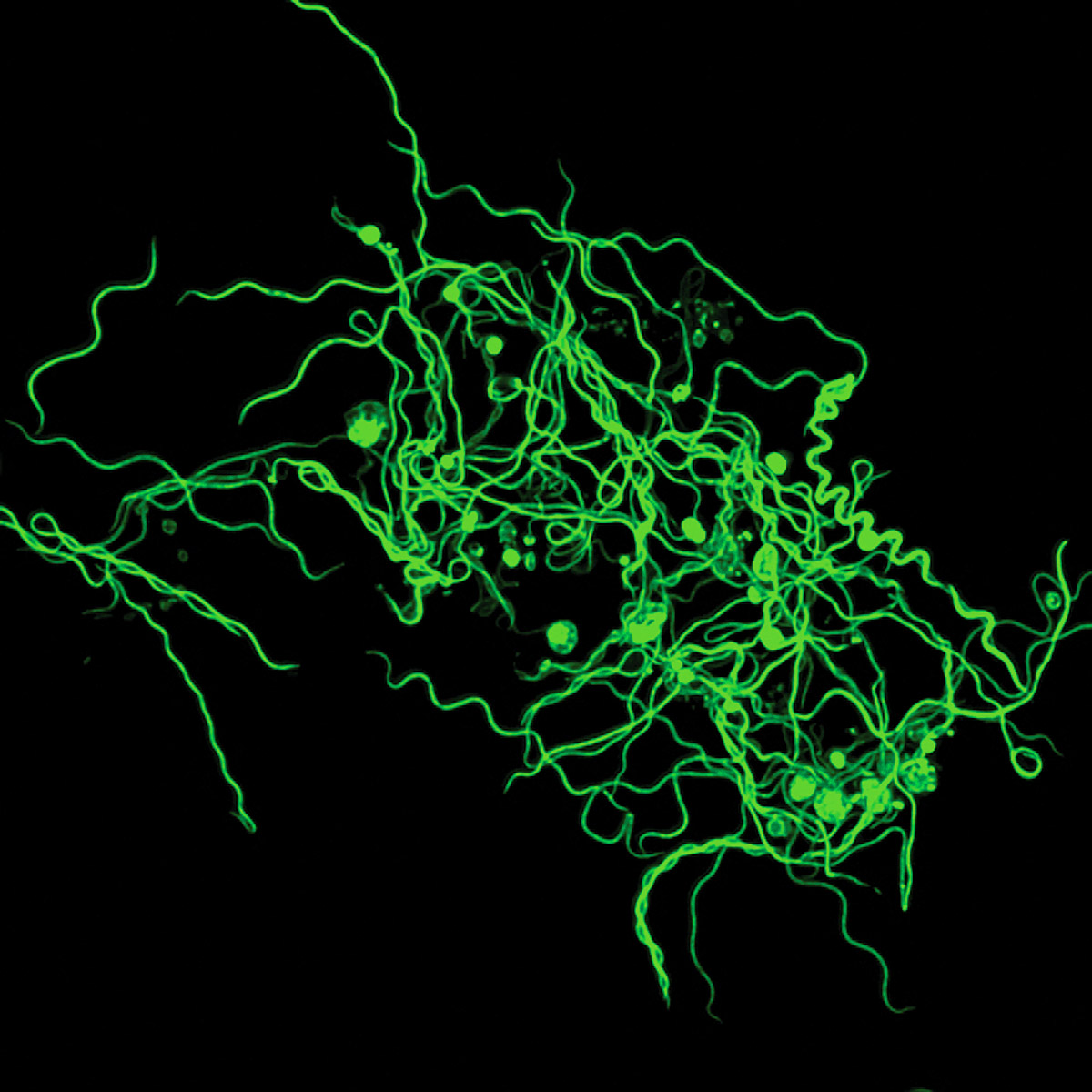

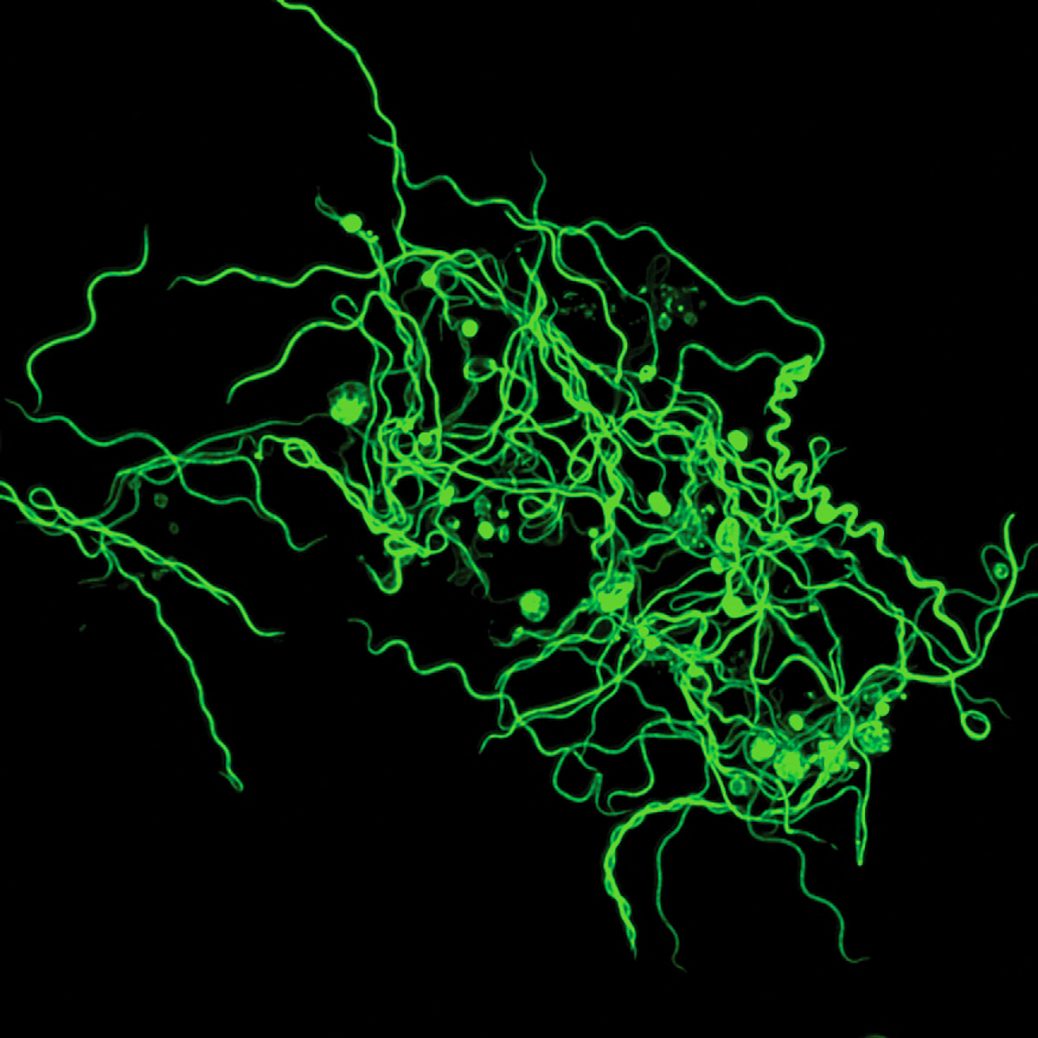

COURTESY OF THE TAL RESEARCH GROUP

Perhaps even more alarming than the disease has been the medical community’s response to it. “I realized that there’s this public health debacle around Lyme, and it’s, for lack of a better word, obscene,” Tal says. Chronic Lyme patients skew female, and for decades, clinicians have dismissed their symptoms as signs of mental illness. The medical establishment has “done nothing but call them crazy,” Tal says, “instead of admitting that they just don’t understand what’s going on.”

Today, there is no objective way to diagnose chronic Lyme, and no medically accepted therapy. For some patients, lengthy treatments with high doses of antibiotics can ease symptoms, but these come with their own serious risks. (They can, for example, damage the microbiome, leading to significant negative effects on health.) And because the antibiotic used currently only prevents bacteria from replicating, Tal notes, it’s up to the immune system to actually kill off the invaders. If immune cells can’t tell friend from foe, the utility of antibiotics may be limited.

Chronic Lyme patients skew female, and for decades, the medical establishment has “done nothing but call them crazy,” Tal says, “instead of admitting that they just don’t understand what’s going on.”

For Tal, these revelations were electrifying. She dove into the immunology of Lyme disease, focusing in particular on sex differences. In one mouse experiment, she discovered that Lyme bacteria “completely disfigured” the uterus. Yet after delving through decades of Lyme research, she could find only one other study that even documented uterine infection.

This shortfall mirrors larger problems in medical research. “We’ve let men dictate the direction of research funding for so long,” Tal says. Traditionally, studies focused on male subjects, and a 1977 FDA policy barred women from participating in most clinical trials in the US in the wake of birth defects caused by thalidomide. It wasn’t until 1993 that federal law required studies to include women and minorities. This, coupled with other sex- and gender-based medical biases, means that many female-dominated diseases remain under-researched. “So much of this research is being done on males, male mice—male, male, male,” Tal says. “And I’m like, no.”

Tal suspects that the sex disparities seen in chronic Lyme and other pathogen-triggered chronic diseases might come down to the fact that men mount a more robust response to acute infection. This no-holds-barred approach is risky—“Your immune system has the power to kill you,” she notes—but it may mean that men, on average, can kill off more viruses or bacteria in the critical first week of infection. After that window closes, the immune system largely settles back down, Tal says. Pathogens that escaped the initial blitz could take up long-term residence in the body, potentially causing persistent symptoms. And women have a higher chance of chronic illness.

Recent Comments