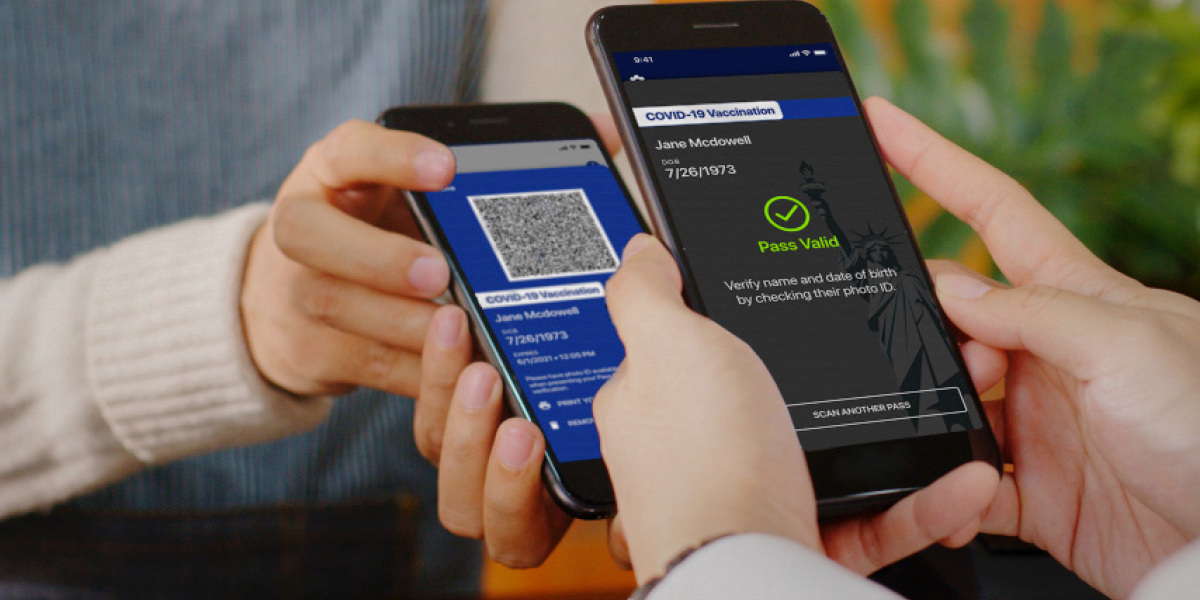

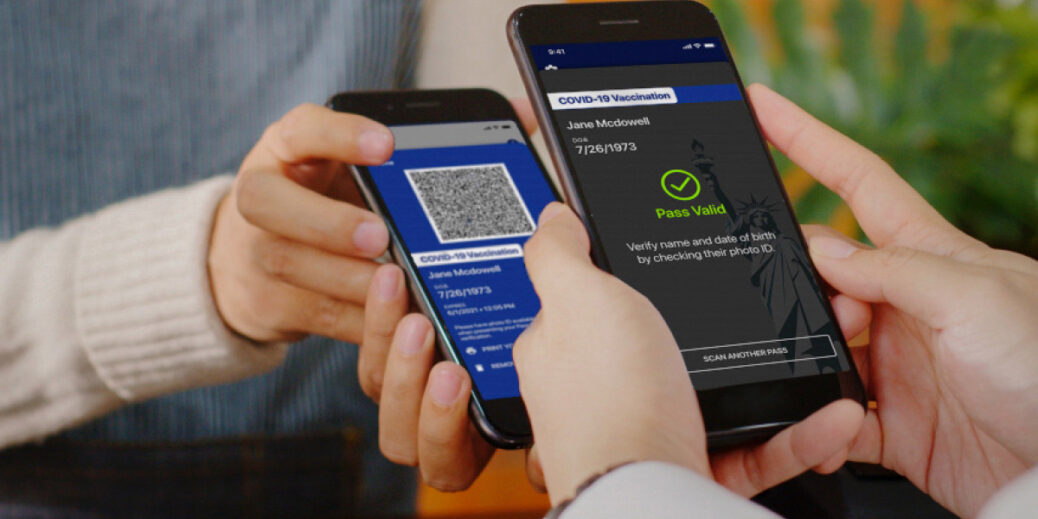

So what is it like to use?

In anticipation of attending my first comedy show in years, at Union Hall in Brooklyn, I registered for the Excelsior Pass. Spoiler: It did not go smoothly.

Downloading the app to my iPhone was simple enough. But like many users, I was greeted with an error message when I tried to register on the website. Many people have been unable to use the pass because it cannot verify their vaccination status. The system works by tapping into state immunization records, but database errors can cause problems, especially if there were data entry errors at vaccine sites. A misspelled name or wrong birthdate can mean that the Excelsior system can’t pull up your record. So when the pass couldn’t verify my identity, I followed the suggestions on the error page and dug up my paper vaccination card to ensure that I was entering vaccine site information correctly. After three attempts, in which I reentered the same information each time, it worked.

After three attempts, in which I reentered the same information each time, it worked.

Limited use

Although I found a use for the pass, it’s been essentially confined to sporting events, gyms, and other high-end leisure venues—which means the pool of users is limited. For working-class New Yorkers who lost low-wage jobs and remain unemployed in the face of mounting debt, entry to a pricey concert or basketball game is well out of reach.

That raises concerns about whether it’s a wise use of resources. The state has spent $2.5 million on the system so far, and under the contract signed with IBM, which developed the platform, it could cost anywhere from $10 to $17 million over the next three years in a scenario where driver’s license information, proof of age, and other data might be added to the pass.

“This passport program feels like a continuation of all the state government’s and Governor Cuomo’s policies around the pandemic,” says Sumathy Kumar, campaign organizer at Housing Justice for All, a statewide coalition of organizations fighting for tenants. “They just want life to go back to normal for people with tons of disposable income.”

And if the pass does get more widespread use—becoming a requirement to enter job sites or essential shops, for example—that raises questions about privacy.

Experts question security

Users must enter their name, date of birth, zip code, and phone number to verify their vaccination status or covid-19 test results. New York State’s website tells users that Excelsior data is safe and secure, while the privacy policy says it does not store the information sent via the app, or use location services to track people’s location. IBM assures users that their data is kept private and secure using blockchain and encryption technologies.

But experts claim the privacy policy is woefully inadequate. Albert Cahn, executive director of the Stop Technology Oversight Project (STOP), which opposes local and state surveillance in New York, points out that businesses use a separate app to scan the pass; when he tested it, he found that a user’s location could potentially be tracked by those scanners. As a result, the comedy club I go to might have a log of my visits there—and to any bars I go to afterwards that require proof of vaccination. Neither New York State nor IBM responded to requests to clarify whether scanning information could be collected or tracked.

The lack of transparency is a problem, says Cahn. “I have less information on how the Excelsior Pass data is used than the weather app on my phone,” he says. Because the pass is not open source, its privacy claims cannot easily be evaluated by third parties or experts.

“If IBM’s proprietary health data standard catches on, they could make huge sums of money… Transparency can threaten their entire business plan.”

Albert Cahn, STOP

But there’s little incentive to be more transparent. In developing Excelsior, IBM used its existing Digital Health Pass, a system it could sell in customized forms to customers from state governments to private companies seeking to reopen their offices.

“If IBM’s proprietary health data standard catches on, they could make huge sums of money,” Cahn says. “Transparency can threaten their entire business plan.”

Privacy and security questions become more urgent if the pass becomes more widely used. The pass is intended to build trust, allowing people to feel comfortable in crowds, yet for many it instead evokes fears of how it could be used against them.

Vulnerable to surveillance

Many groups have genuine, well-founded concerns over tracking and government surveillance. Historical precedent shows that the use of such technologies, even if limited initially, tends to spread, with especially damaging results in Black and brown communities. For example, anti-terrorism legislation passed in the weeks after the 9/11 attacks expanded surveillance, detention, and deportation of undocumented Muslim and South Asian immigrants.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a digital civil liberties organization, has adopted a strong stance in opposition to vaccine passports. “Mostly these apps are a waste of time and money,” said Alexis Hancock, director of engineering at EFF. “Governments really need to consider the resources they have in place and allocate them toward getting the public to a better place after the pandemic, not putting people in a position of more paranoia and privacy concerns.”

Recent Comments