(CNN) — If there’s one thing we know about Venice, it’s that it’s unique. What other city is built on water, or packed with its signature flamboyant architecture?

It turns out, quite a few.

The Republic of Venice — or the Most Serene Republic of Venice, to give it its full name — existed for 1,100 years, from 697 CE to 1797 CE, when Napoleon conquered the city.

It’s an astonishing length of time for a period when upheavals, coups and conquerings were regular events.

And as it gained in power, it built a pseudo empire along the Adriatic — not so much on the Italian side, but on the eastern coast, in countries such as modern day Slovenia, Croatia, Albania and Greece. Its tentacles even stretched as far as Crete and Cyprus.

As one end of the Silk Road trading route, the city-state was one of the most cosmopolitan in Europe, taking inspiration for its frothy architecture and glittering interiors from all over the globe. And it took that outré look with it, to the towns it ruled and allied with.

That means that the eastern side of the Adriatic was once littered with mini Venices — not crisscrossed with canals, but with the lion of St Mark, Venice’s emblem, sculpted onto city walls; elaborate wells in Venetian-style campi (squares); and those famously flamboyant buildings, with porticoes, frilly-edged windows, and, everywhere, campanili (belltowers) looking like the one in St Mark’s Square.

Today, many of these mini Venices remain. Here are some of the most atmospheric.

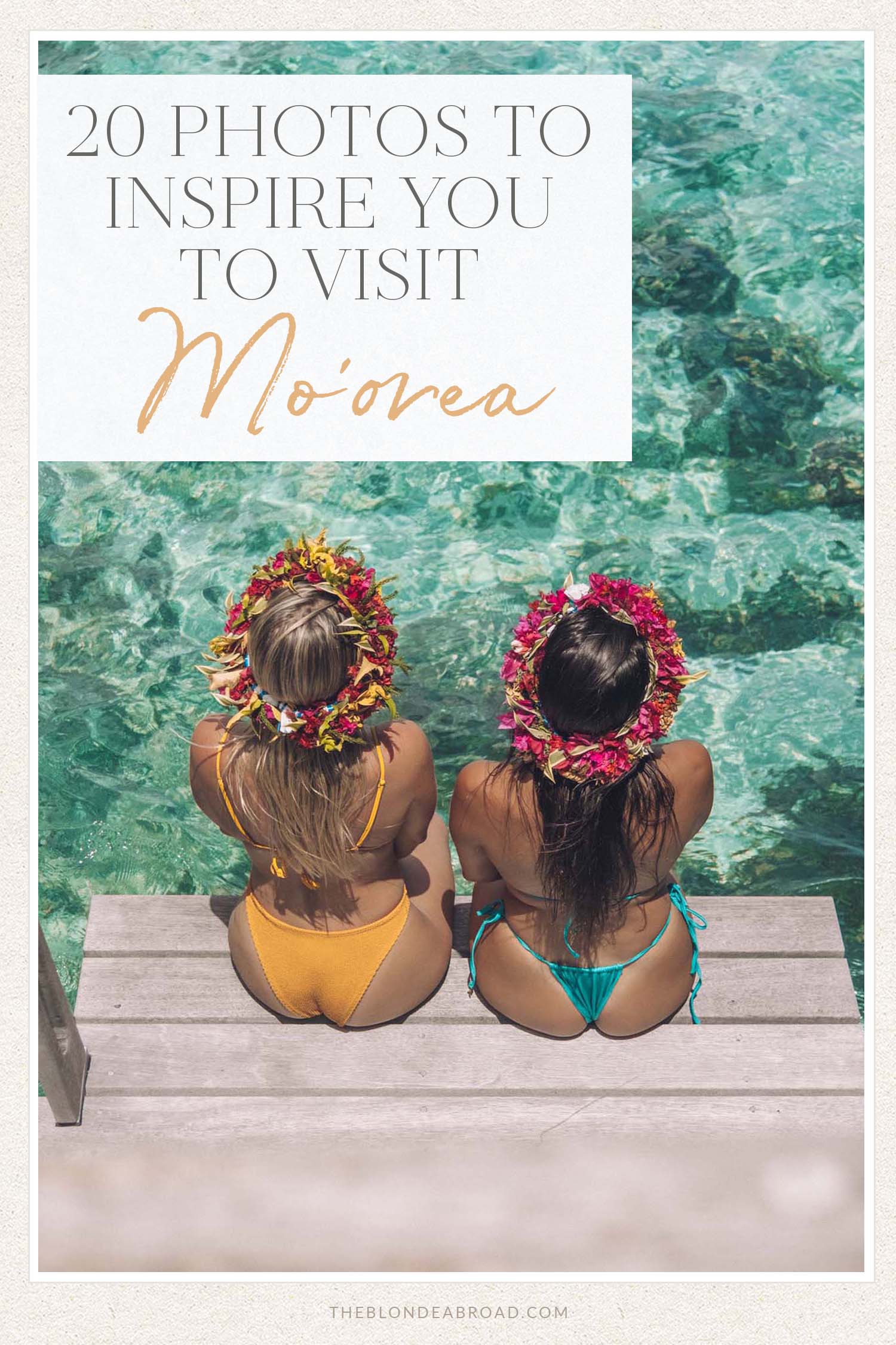

Piran, Slovenia

Pretty Piran could double as a Venetian waterfront.

Jure Makovec/AFP via Getty Images

Calling to you from sea and land alike, the belltower of pretty Piran is a dead ringer for the famous campanile of St Mark’s Square.

This is Venice, if Venice were a village. Part of the Venetian Republic from 1283 to 1797, when the Austrians took over, it was a semi-autonomous town. Not that it’s stuck in the past — it’s thought to be the first town in the former Yugoslavia to elect a Black mayor, Ghanaian-born Peter Bossman, who was elected in 2010.

Sure, there are no canals, and the little fishing boats moored in the center of town are a far cry from the ferries and cruise ships in Venice, but this little oasis of calm on the Adriatic has frothy Venetian-style buildings on Tartini Square, including the 15th-century red, Gothic “Venetian House,” and a lion of St Mark on the town hall. That campanile? It belongs to the cathedral of St George, perched high on the rocks.

Istria — this huge, wedge-shaped peninsula at the northern end of the Adriatic — is littered with Venetian towns. Today, it’s mostly part of Croatia, with a sliver at the top based in Slovenia. Take a coastal roadtrip and you’ll see Venetian-style campanile after campanile.

Izola, nearby, is very similar.

Koper, Slovenia

The Da Pontejev fountain is a replica of Venice’s Rialto Bridge.

Alamy

Found the Rialto Bridge in Venice too crowded? Hop two hours east and across the Slovenian border to Koper, where the city’s Da Ponte fountain (Da Pontejev vodnjak) is a reproduction of Venice’s most famous bridge. The mini Rialto, commissioned in 1666, is just one of many Venetian elements — this was once the capital of Venetian Istria. In fact, it sits almost directly opposite Venice, with the Adriatic in between.

The Praetorian Palace was inspired by the Doge’s Palace.

PatrikSlezak/iStock Editorial/Getty Images

The cream-colored, turreted Praetorian Palace has a grand outdoor staircase that reminds you of the Doge’s Palace, and the Cathedral of the Assumption has a Venetian belltower, a Venice-cast bell and a work by Carpaccio, one of Venice’s greatest Renaissance artists.

Grado, Italy

Built on a series of islands inside a lagoon, Grado has a lot in common with Venice.

De Agostini/Getty Images

Cantilevered over an island-filled lagoon on a sandbar of its own, Grado seems familiar. In fact, this, in neighboring region Friuli Venezia Giulia, 90 minutes northeast of La Serenissima, is known as the “mother of Venice,” being founded in Roman times but home to refugees fleeing from the mainland in the fifth and sixth centuries — like Venice.

The bishops of nearby Aquileia moved their HQ here, allying themselves first with the Byzantines and then with Venice. That’s why you’ll see the Campo dei Patriarchi — as in Venice, a square is called a campo not a piazza — with its churches that resemble those on Venice’s Torcello island, a Venetian-style belltower, and long swathes of sand, like the Venice Lido.

Corfu Town, Greece

Corfu Town is one of the most elegant settlements left by the Venetians.

Paul Panayiotou/Corbis Documentary RF/Getty Images

At the mouth of the Adriatic, the Ionian islands were a key part of the Venetian territories, and the UNESCO-protected Corfu Town is one of the best examples of the Republic’s influence.

The French wrested control in 1797 when the Republic fell, but beforehand, the Venetians had built no fewer than three fortresses, which still exist — as do the countless pastel-colored, Neoclassical palazzos and stately loggias that line it.

Other Venetian settlements in Greece include Nafplio, on the Peloponnese; Cycladic island Syros; and Crete, where a Venetian lighthouse still looms over the harbor at Chania.

Svetvincenat, Croatia

The main square of Svetnincenat, Croatia, is a dead ringer for a Venetian campo.

Istria Tourist Board

First things first: this isn’t on the water. Yet, half an hour due north of Pula, and deep inside the Istrian peninsula, this pretty village still exudes Venetian style.

But the sight that’ll whisk you straight over to La Serenissima is the main square. Istria’s finest example of Renaissance town planning, its church and belltower overlook neat houses, a loggia, and a typical Venetian well. Wondering what residential Venice looked like in the 1500s? This is it.

Chioggia, Italy

Chioggia sits at the southern end of the Venice lagoon.

Raquel Maria Carbonell Pagola/LightRocket/Getty Images

When the crowds get too large in Venice, take the vaporetto to the Lido island and hop on the number 11 ferry, which will cleave through the lagoon, ending at Chioggia — perched on five islands, at the southern end of the Venetian lagoon.

Much of this fishing town will seem familiar: the pretty canals, straddled by ancient bridges; the grand palazzos; the art-stuffed churches; and the shimmering lagoon views with the Dolomites in the background.

Unlike Venice, though, cars are allowed into Chioggia, so the main street is a busy road, and some of those cutesy bridges have cars driving over them.

It’s also a major fishing town still, and you’ll see the big boats parked up below the church of St Dominic, as well as folk art by said fishermen in the church itself.

Rovinj, Croatia

Another mini Venice on the Adriatic, Rovinj may be a popular destination, but it’s still a tranquil retreat compared to the mother city. Today part of Croatia, this fishing town on the Istrian peninsula was shuttled between the Byzantines, Dubrovnik and Aquileia (another town linked to Venice) before ceding to La Serenissima in 1283, in return for their protection.

Does the belltower of St Euphemia cathedral look familiar? That’s because it was modeled on St Mark’s. The slim, eye-catching chimneys also date from Venetian rule.

Today, once you’ve taken in the lions of St Mark dotted around town, take a walk along the seafront. You’ll wind past thick pine trees to the startlingly modern Hotel Lone, which looks — perhaps fittingly for its Venice links — like a giant cruise ship overlooking the Adriatic.

Muggia, Italy

Wedged deep in the Adriatic’s “armpit,” two hours east of Venice on the border of Slovenia, pretty little Muggia is another villagey Venice. Its stout belltower dominates the town, which entered into the Venetian Republic in 1420 — you’ll get a pretty view from the port, where small yachts dock.

You’ll find the lion of St Mark on the town hall’s lemon façade, the bone-white cathedral (sculpted like flower petals) is early Venetian Gothic, and the Renaissance-era homes of Calle Oberdan are Venetian in style (though not set on a canal). The dialect, traditional costumes and signature dishes are also Venetian — although today this is part of Friuli Venezia Giulia.

Korčula, Croatia

Locals say that famous Venetian Marco Polo was born on Korčula, Croatia.

Ivo Biočina/Croatian National Tourist Board

Explorer Marco Polo is synonymous with Venice, but what Venetians won’t tell you is that he was actually born on the island of Curzola, as it was called, or Korčula, in modern-day Croatia, around 400 miles southeast of La Serenissima. Or at least, that’s what the Croatians say — Venetians call it fake news. His exact birthplace is still disputed.

Today, you can visit what Korčula locals say is his birthplace (or a later house built over said birthplace), or hit the 15th-century St Mark’s Cathedral, which not only is named after Venice’s patron saint, but contains two works by superstar Renaissance painter, Tintoretto.

The Venetian lion on the Korčula city walls.

Ivo Biočina/Croatian National Tourist Board

Under communist rule post WWII, much of the Venetian heritage — like the lions of St Mark that were dotted around the island — was destroyed. However, the Italian influence lingers on: the city walls are Venetian, a lion guards the entrance gate, and words of Venetian dialect spatter the locals’ chatter.

Nicosia, Cyprus

Nicosia’s Venetian walls are still standing, though the city is divided.

Savvas Njovu Christides/iStockphoto/Getty Images

The Republic of Venice dominated the Mediterranean as far as Cyprus — in fact, every September 5 to this day, Venice celebrates the moment queen Caterina Cornaro handed over the island to the Venetians with a watery parade down the Grand Canal.

There are Venetian ruins and walls in Famagusta, in Northern Cyprus — the de facto state in the north of the island, which is only recognized by Turkey. But perhaps the most spectacular mark they left on the island were the star-shaped walls of capital city, Nicosia.

Today, Nicosia is split in half — the border between the Republic of Cyprus and Northern Cyprus cuts straight through it — but the walls, designed in 1567 by Giulio Savorgnan and Francesco Barbaro, remain.

Looking like a star, a comet, a sun, or even a Covid-19 cell, depending on how you view it, the complex is best admired from above.

Editors’ note: This story has been updated to reflect the disputed origins of Marco Polo.

Recent Comments