Overseas business groups like the American Chamber of Commerce in China say the country’s sustained restrictions and lack of a clear exit plan have undermined confidence and created uncertainty.

“Our members feel that the business environment has become a lot less predictable, largely due to the pandemic and its related restrictions,” said Colm Rafferty, the group’s chairman.

Residents have cited the economic impact as one of many reasons the lockdown has affected their mental health.

As the Shanghai lockdown began this spring, local searches for “psychological counseling” on the Chinese search engine Baidu increased more than 250 percent compared with the same 30-day period a year earlier, according to Baidu Index. In a survey by Data-Humanism, a blog about data journalism, about 40 percent of Shanghai residents surveyed in mid-April reported having depressive tendencies in the previous two weeks of lockdown.

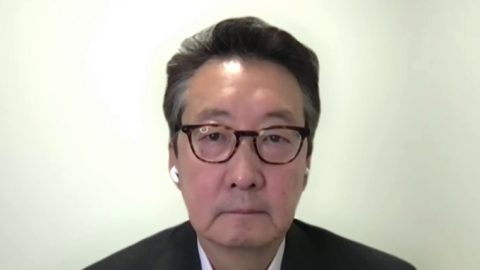

“Nobody was unaffected,” George Hu, president of the Shanghai International Mental Health Association, told NBC News.

Residents have struggled with anger, frustration and feelings of hopelessness, he said, as well as fears that their pre-existing mental conditions could be exacerbated by social isolation and lack of access to professional care.

“How many people died or suffered from a non-Covid condition as they couldn’t get the care they used to have, including for mental health?” said Hu, whose colleagues have themselves been driving around the city delivering medication to patients.

Chinese officials say their strict “zero-Covid” strategy, which has kept virus cases and deaths far lower than in the United States and other countries, is necessary to prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed. But that approach has been challenged by the highly contagious omicron variant of the virus.

Recent outbreaks across the country have led to lockdowns and other measures affecting hundreds of millions of people, although officials appear to be trying to avoid a full lockdown in Beijing, the capital, where there is a much smaller outbreak than in Shanghai.

Lockdowns early in the pandemic, like the one in Wuhan, were easier for residents to understand, Hu said, as there was little known about the virus or how to treat it.

But when the same policy was applied in Shanghai two years later, “the reasoning behind the lockdown did not make sense to many people,” he said, “and that causes psychological distress.”

A notice released by the local government early this month offered tips for protecting mental health and pointed to resources online, at mental health centers and by phone.

Some residents have been pushing back against continued restrictions, with videos circulating online of crowds arguing with neighborhood committees. Official social media posts celebrating Shanghai’s gradual return to normal life have also been challenged by online commenters who say nothing has changed for them.

“I’m still under lockdown, but you say the hustle and bustle is coming back. It’s a big joke,” said one comment on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter.

Recent Comments