Bundled into a police van, beaten and crammed into a cramped Belarusian cell with dozens of others, Aleksei V. hadn’t realized it was possible to feel such fear.

“I could never imagine being so scared in my life,” Aleksei, 40, a marketing manager, recalled of his ordeal in the detention station after tens of thousands of protesters rejected the outcome of the Aug. 9 presidential election.

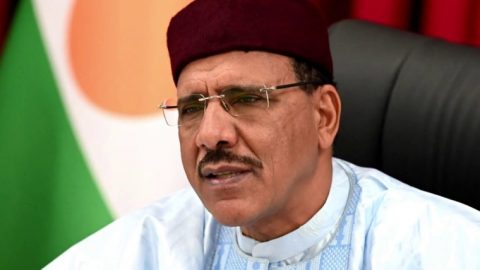

Strongman Alexander Lukashenko, who has been pictured in a protective vest and carrying a rifle on several occasions, still clings to power after 26 years while the protests continue.

Now, as pressure grows on Lukashenko at home and abroad more than three weeks after the election, personal accounts are emerging of the Belarusian regime’s fervor in stopping the biggest show of discontent in the country’s modern history.

Aleksei and another man with whom NBC News spoke allege that they were subjected to police brutality after having been detained in the days following the election.

Not every aspect of their stories could be verified, but they described similar conditions and treatment in custody — beatings, cramped cells, little to no food or water for days. Similar allegations were reported by international human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

Aleksei, who has a young daughter and did not want his full name used for fear of retribution, spoke by phone from Minsk a week after his detention — after having seen a psychologist because of a sudden stammer he said he developed while in custody.

Although he was later charged with attending an “unsanctioned mass gathering,” he maintains that he was not there to protest but was instead out for a walk with a couple of friends, although he said he considered joining in if the rally was peaceful.

Court documents seen by NBC News confirm that he was detained in a park the evening of Aug. 10, the day after the election, as protesters gathered in central Minsk.

He said he was crammed in a police van with five other people and taken to the city’s Okrestina detention center.

After getting out of the vehicle, he said, he was hit with a baton on his back, a shoulder, his groin and his buttocks by masked men in uniforms.

After that, Aleksei said, he and 79 other people, all men — including several teenagers and journalists — were crammed into a small prison cell, where he said they had to stand, with nowhere to sit, for nearly 30 hours.

During the entire time, they were given a 2-liter bottle of water and a loaf of bread for all 80 people to share, he said. Toilet access and medical help were also limited, he said.

The next day, he said, they heard people in other cells demanding food and water, after which they heard them being led out of their cells and harshly beaten.

After hearing their screams and groans, Aleksei said, he and his cellmates huddled together, expecting that they would be next.

“I could hear their hearts beating,” he said.

NBC News could not independently verify the details of his treatment, with Belarusian authorities not commenting on the treatment of individual detainees.

But as personal accounts of detainees like Aleksei started to emerge, Deputy Interior Minister Alexander Barsukov said there had been no abuses at Okrestina.

Aleksei’s account was echoed in testimonies published by several human rights organizations.

Citing a woman who said she had been detained, Human Rights Watch reported that police officers mistreated and humiliated people detained during the protests, viciously beating them and cramming them into small cells while depriving them of food, drinking water and medical aid.

Amnesty International also collected testimonies from protesters who described being tortured or subjected to other ill treatment in detention centers, including being stripped naked, beaten and threatened with rape while listening to the screams of other victims.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and alerts

Aleksei said that around Aug. 13, he and half of his fellow detainees were transferred to a more spacious cell with running water, where they could stretch their legs and were given more food.

On Aug. 14, he said, he was taken out of the detention center in a police van and released in Minsk with no explanation.

Since he was released, Aleksei said, he has had trouble eating and sleeping.

“I felt like I was some sort of animal,” he said. “I really hope the people who beat and tormented us will be held accountable one day. I don’t want to have to cross the street every time I see a police officer.”

He said he has since submitted a complaint about the treatment, but he is too scared to talk to the investigators in person out of fear that he might be detained again.

Aleksander Luhanin, 36, a video game developer, was also detained the evening of Aug. 10 as he walked home through central Minsk, court documents show. He said he saw small groups of protesters chanting as riot police looked on.

After he saw the police charge, he said, he ran toward a park, where he was surrounded and detained. He said he was crammed into a police van with six other people, some of whom already looked badly beaten, and was taken to Okrestina.

He was put in a tiny prison cell with 67 other people, with no room to sit, for about 24 hours, he said.

“No one could sleep in that position, so we took turns squatting by a wall for 15 minutes at a time so we could doze off,” he said.

Periodically, he said, they could hear groups of people being taken out of their cells and beaten.

“It was creepy to stand there and have to hear it all,” he said. “Everyone was paralyzed with fear and silent.”

NBC News could not independently verify the details of Luhanin’s account, either, with Belarusian authorities not commenting on the treatment of detainees.

He said they got water every two to three hours but had access to a toilet only twice in that time.

Luhanin said he and 21 other men were eventually moved into a more spacious cell and given food.

He said he and his cellmates were made to stand facing the wall for seven hours before they were transferred to another detention center, which turned out to be about 60 miles from Minsk.

From there, he said, he was released Aug. 14 with no possessions. Luckily, he said, he was met by volunteers waiting outside, who gave him water, food and cigarettes.

Holga Zalatar, 37, a mother of five, is one of hundreds of volunteers who have spent days, and sometimes nights, standing outside the walls of Okrestina — waiting for detainees to emerge.

Zalatar is in charge of keeping lists of those who have been released. She said it was a 24/7 operation, with a team of doctors, lawyers, psychologists, cooks and priests ready to help. Zalatar said that people would often come out disoriented and in a state of shock — but that remarkably, many were in good spirits.

“I am standing there shrinking from the horror of what they have lived through, and they smile back and say everything is OK,” she said.

“And that’s when you understand that they have not been broken. That they are strong, and they did not succeed in intimidating them,” she said.

Aleksei and Luhanin were charged with taking part in an unsanctioned gathering, according to court papers — a charge both men deny. Their court documents show that they were tried in special court hearings at Okrestina.

The Belarusian rights group Spring 96 has both men’s names on the list of detainees held at Okrestina.

Their names are also on a Supreme Court list of detainees sentenced to administrative two-week arrests for their part in the protests. The list does not mention the charges.

Luhanin said that looking back, he was lucky to escape with just a few bruises compared to much more serious injuries other detainees have described to the media and human rights organizations. But although he feels physically fine, he said, the emotional scars will linger.

“The insults and intimidation affected my emotional state,” he said. “They treated us like animals. One of my cellmates was an old man who spent 20 years in Soviet labor camps, but he said he has never experienced such brutality.”

While in custody, Luhanin had no idea what was happening in the country, so he was surprised to learn that the protests were still going on when he got out.

The day he was released, tens of thousands of factory workers and women clutching white flowers and balloons flooded the streets of cities across Belarus for the fifth straight day. The rallies continue more than three weeks after the disputed election.

“It was good to know everything wasn’t in vain,” Luhanin said. “That people rose up.”

Recent Comments