JERUSALEM — With long strands of bougainvillea draped from its balconies, the mansion on Jerusalem’s Agron Road might seem an unlikely stage for a test of wills between the Biden administration and Israel’s coalition government.

Until 2018, the stone building housed the U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem and America’s diplomatic mission to the Palestinians. But the Trump administration closed it down and merged it into the new U.S. Embassy in the city, Israel’s capital.

It sent a clear message: Relations with the Palestinians had been reduced to a portfolio within the American-Israeli relationship.

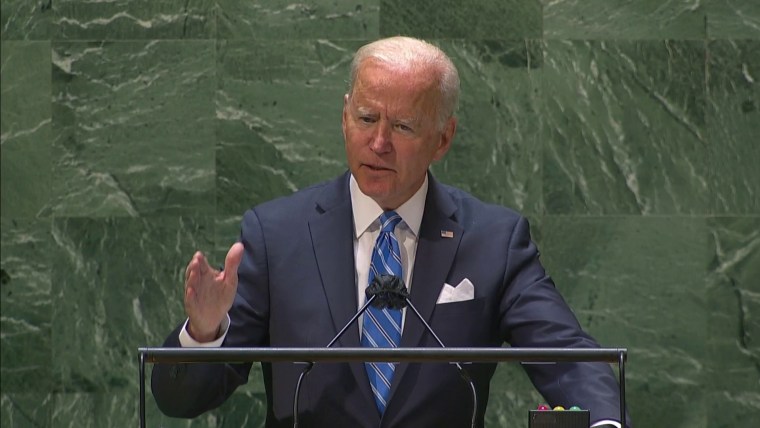

President Joe Biden took office promising to reopen the consulate and use it to rebuild diplomatic ties with the Palestinians.

Ten months later, the consulate remains closed in the face of staunch opposition to reopening it from many ministers in Israel’s coalition government. The Israeli right regards it as a sign of U.S. ambitions to one day divide Jerusalem into a shared capital for both Israel and a future Palestinian state — an idea they say is completely unacceptable to them.

“We will not compromise on this,” Gideon Saar, Israel’s justice minister, said at a conference last month, adding that he and Prime Minister Naftali Bennett were “on the same page” on the issue.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

The consulate has also taken on symbolic importance for the Palestinian Authority, but for far different reasons.

“We want the American Consulate to constitute the seed of a U.S. embassy in the State of Palestine,” Mohammad Shtayyeh, the Palestinian prime minister, said in a Facebook post in September.

The opposition on the Israeli right has left plans for the consulate in limbo. Legally, the U.S. needs Israel’s permission to open it, meaning the Biden administration cannot simply ignore the government’s position.

But State Department spokesman Ned Price said at a news briefing Wednesday that the U.S. had “been very clear about our intentions” to reopen the consulate.

The issue is one of several recent points of friction between Jerusalem and Washington when it comes to Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories.

Late last month the U.S. joined the United Nations in condemning Israel’s decision to approve more than 3,000 settlement homes in the West Bank — the first large-scale settlement expansion since the country’s government took office in June.

The State Department called the move “completely inconsistent with efforts to lower tensions” although no further action was taken.

The U.S. also said it received no warning that Israel planned to designate six Palestinian rights groups as terrorist organizations before it did so last month. Israel accused the groups of funneling resources to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a militant group.

All six have denied the allegations and accused Israel of attempting to silence groups that expose abuses committed by Israeli security forces.

Shawan Jabarin, the director of one of the groups, Al-Haq, urged the White House to put pressure on Israel to reverse the designations.

“This is a test for Biden’s slogans that human rights and rule of law are central to U.S. policy,” he told NBC News in a telephone interview on Tuesday. “It’s time to translate slogans into action.”

Israel’s top foreign policy priority now, however, is Iran, not the Palestinians. The country’s ministers have focused on Tehran during meetings with their American counterparts, and Bennett also brought it up during his first White House sit-down with Biden, in August.

They have raised concerns about Biden’s promise to rejoin the Iran nuclear agreement, which former President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of in 2018. The deal hinges on Iran agreeing to accept curbs on its nuclear program in return for a lifting of sanctions by the U.S. and five other world powers.

The subject will likely be raised during talks between the U.S. and Iran that are set to resume in Vienna this month after a five-month pause following the election of Ebrahim Raisi, a hard-liner, as president.

Politicians from across Israel’s political spectrum oppose the deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), arguing that it was never strong enough to stop Iran from trying to build a nuclear bomb.

Iran has consistently said that it does not seek such a weapon and that their nuclear program is for civilian purposes.

While former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu railed publicly against negotiations with Iran, the current government is voicing its concerns to the Biden administration in private.

Two Israeli officials, speaking on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media, told NBC News on Wednesday that they were encouraged by a recent shift in language from the U.S.

“Every option was on the table” regarding Iran’s nuclear program, Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s told CBS’ “Face the Nation” on Sunday, although he stressed that the Biden administration believed that diplomacy was the best path forward.

Those words have been backed by recent military displays. An American B-1 bomber flew over Israel on Sunday flanked by Israeli aircraft. And the U.S. announced it had successfully dropped a powerful “bunker buster” bomb — the type needed to penetrate a fortified Iranian nuclear facility — from an F-15 fighter jet during a mid-October test from Eglin Air Force Base in Florida.

But the U.S. and Israel still remain divided on the goal of diplomatic talks with Iran. The White House hopes to reinstate the nuclear deal with Iran as a first step and then negotiate stricter conditions on top. Israel believes that once the deal is restored — and sanctions on Iran are lifted — Tehran will no longer feel pressured to negotiate.

“The Americans believe they will have the capacity to further negotiate after JCPOA,” one of the Israeli officials said. “We believe that we need to stride directly towards an agreement that is longer and stronger.”

Recent Comments