The airstrikes may have ended, but the trauma lives on.

As the cease-fire between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas holds in the short-term, parents like Randa Yousef are afraid about the long-term effects the latest round of violence will have on their children.

Her daughter Kinda, 5, “used to play and laugh” at their home in Gaza City, but now “she cries and screams and calls for me,” Yousef told NBC News by phone last week.

A video she recorded during the fighting shows Kinda crying on her bed, telling her she is afraid they are going to die and their house will be destroyed.

Now even the slightest noise terrifies her and she is worried it could be another Israeli airstrike, Yousef said.

Elsewhere, in Khan Yunis — a city in the south of the long impoverished and blockaded Gaza Strip — Fadi Ali Abushammala said he used painting as a way to distract his sons — named Ali, 11; Karam, 7; and 3-year-old Adam — from the conflict. Now, they draw pictures of dead bodies.

“I asked my kid, ‘What did you paint?’ He says that ’this is a dead man and his son, his kid, is crying,’” Abushammala said Monday.

Among the 243 people who died during the conflict, 66 were children, according to the Gaza Ministry of Health.

Those living in the densely populated Gaza Strip were particularly vulnerable to the bone-rattling airstrikes because there are no bomb shelters and there is nowhere for most of its 2 million people to go.

“Everyone talks about the lack of safe places,” Dr. Samah Jabr, head of the mental health unit at the Palestinian Ministry of Health, said Tuesday. “There are no bunkers. People don’t know where to hide.”

While rocket attacks from Hamas are terrifying, Israel has a comprehensive system in place to protect its citizens. All public buildings — such as malls, hospitals, houses of worship and theaters — are required to have bomb shelters, and some children’s playgrounds in the south of the country do, too.

Modern homes and private buildings are also required to have safe rooms, and cities run public shelters that are opened during times of conflict by the Israel Defense Forces’ Home Front Command.

Many of the thousands of rockets fired by Palestinian militants from Gaza were also brought down by Israel’s Iron Dome anti-missile system. Israelis are also alerted to incoming munitions by sirens and app notifications. Schools send videos on how to talk to kids and explain what is happening to try to relax them.

The Israeli military said that while it pursued its aggressive military campaign, it tried to “minimize civilian casualties.”

Nonetheless, Israeli psychologist Mooli Lahad, who has 40 years’ experience working on both sides of the border and around the world, said,“You have a whole generation of kids who don’t know anything but living under these sporadic and sometimes intensive bombardments.”

“We are witnessing a level of trauma and destruction that is beyond belief,” added UNICEF’s special representative to the state of Palestine, Lucia Elmi. “It’s something that we’re going to continue to see for generations to come.”

Before this wave of violence, the United Nations Children’s Fund reported that 1 in 3 children in Gaza required mental health and psychosocial support. Now, it fears the number has increased, Elmi said.

Eleven children were already receiving care for trauma as part of the Norwegian Refugee Council’s psychosocial intervention program,the independent humanitarian organization said Tuesday.

The NRC’s education coordinator in Gaza, Asad Ashour, said the escalation in violence had exacerbated the symptoms the organization was already trying to treat.

“It’s difficult to convince them that the future is bright,” he said last week.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Both Ashour and Lahad said children on both sides of the border suffer with poor concentration, nightmares, shifts in personality, agitation and the constant fear death could be imminent for them or their friends and family.

“When you go to a park, you enjoy it. You don’t always think, ‘A missile might fall on my head,’ but for them, it’s always partially on their mind to be on guard. It’s exhausting to the system,” Lahad said.

As a result, he said he found children in Israel and Gaza “regress” by avoiding school and visiting friends, and they are less likely to try new things.

“It takes some time to realize that a sudden noise does not mean a threat,” Lahad said.

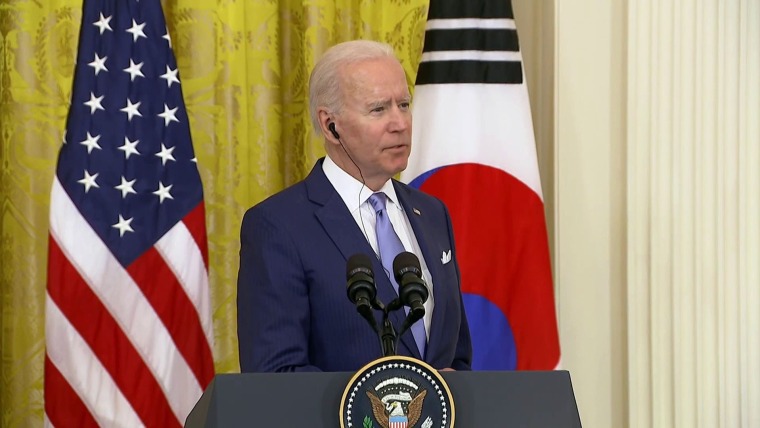

President Joe Biden said Friday there has been no shift in his commitment to Israel’s security, but insisted a two-state solution that includes a state for Palestinians remains “the only answer” to the conflict.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who has been in close touch with regional leaders, also plans to travel to the region to meet with Israeli, Palestinian, and other counterparts in the coming days to discuss “recovery efforts and working together to build better futures for Israelis and Palestinians,” Ned Price, a State Department spokesperson also said Friday.

But the unpredictability of the region and the constant threat to safety, has led Jabr of the Palestinian Ministry of Health to believe the trauma experienced by Palestinians cannot be defined as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“PTSD best describes the experience of soldiers who go back to the safety of the home and they disconnect completely from the traumatic experience,” she said.

“For Palestinians, traumatic threats are repetitive and ongoing,” she said, adding that there is no “post-trauma” and fears for safety and the feeling of helplessness carry on even after a cease-fire.

In the meantime, all mental health professionals can do is try to heal the generational scars and provide what she calls palliative care through therapy, she said.

Recent Comments