SYDNEY — First it was beef. Then it was lobsters. Now, it’s Covid-19 vaccines.

A series of economic and diplomatic clashes between China and Australia has extended to regional vaccine outreach, with the Pacific country of Papua New Guinea becoming the latest flashpoint.

The two rivals have offered pandemic aid to Papua New Guinea, but China recently accused Australia of “vaccine sabotage” there for trying to denigrate and block the use of China’s Sinopharm vaccine. It’s an allegation that points to the increasingly tense geopolitics of the vast Pacific region, where China and Australia are jockeying for influence.

“This is consistent with a pattern that has emerged over the last couple of years,” said Graeme Smith, a fellow at Australian National University’s Department of Pacific Affairs. “Portraying Australia as not on the side of the Pacific is now part of China’s playbook.”

The rivalry has major consequences for the brewing tension between the U.S. and China. Australia and the U.S. are staunch allies who spent decades building diplomatic and military ties throughout the Pacific.

But in the last 20 years, China has gone from having virtually no presence in the region to being the third-largest aid donor there, along with having significant investment and trade in many countries.

“China’s presence has expanded rapidly, which is completely in line with what is happening everywhere else in the world,” Smith said.

‘Political manipulation and bullying’

With a population of almost 9 million, Papua New Guinea is one of the most culturally diverse countries on the planet, with thousands of distinct communities living across its rugged and remote landscapes.

Like many developing countries, it turned to the international community for assistance with a Covid-19 vaccine rollout, made all the more urgent by a spike in cases starting in March.

China dropped a bombshell last month when the Chinese Communist Party English-language newspaper Global Times accused Australia of “vaccine sabotage.” Australia was “threatening senior officials from welcoming Chinese vaccines,” it claimed.

Afterward, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said Australia was “tak[ing] advantage of vaccine issues to engage in political manipulation, bullying, coercion [and] being callous to the life and health of the people in Papua New Guinea.”

In the weeks since then, Australia has flatly denied the accusations.

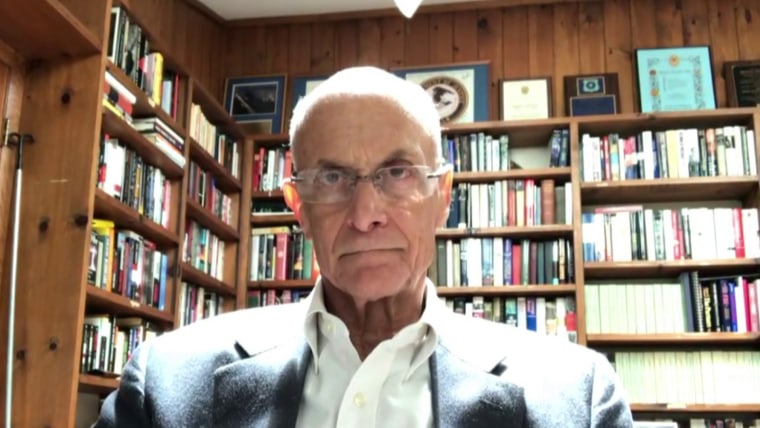

“The Australian government rejects these assertions,” Australia’s minister for international development and the Pacific, Zed Seselja, told NBC News.

“Public health is a global shared interest,” Seselja said. “Decisions about vaccine approval and usage are sovereign matters for the countries in which they are used.”

But others in Australia are using far stronger words about the incident.

Jonathan Pryke, the director of the Pacific Islands Program at the Lowy Institute, a think tank, slammed China’s claims, saying the “bluster” was distracting from the reality on the ground.

Australia has sent 28,000 AstraZeneca doses to Papua New Guinea since March, in addition to having contributed to the global vaccine alliance COVAX, which has delivered 278,000 doses. It has also given millions of dollars for a raft of other pandemic response measures.

China has provided 200,000 doses of its Sinopharm vaccine, but the delivery was delayed until June, as Papua New Guinea was waiting for the Chinese-made vaccine to get World Health Organization approval, which came in early May.

But in that time, Pryke said, Papua New Guinea went from experiencing a vaccine supply problem to dealing with problems around the logistics of a national rollout, with some current vaccine stock now on the verge of expiring.

“There’s huge challenges around actually getting these vaccines into people’s arms. And Australia has really tried to stand up to [these challenges]. … Meanwhile, China has only been making some tokenistic efforts,” he said.

According to Papua New Guinea media, of the 200,000 Sinopharm doses donated by China, only 4,000 have been administered, most of them to Chinese citizens.

“So there’s been a lot of bluster from China and not a lot of action,” Pryke said.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Affairs Ministry pointed to an earlier statement from Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian.

China’s vaccine efforts in Papua New Guinea “are a manifestation of China’s pledge to make vaccines a global public good in Pacific Island countries, and a concrete action taken by China to promote the building of a global community of health for all,” he said.

Meanwhile, Australia is dealing with challenges to its own vaccine rollout back home, which has been called “a colossal failure“ by former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull for its lack of speed and its shortages in some areas.

The bigger issue

China and Australia have been jostling for influence over the Pacific region, an area made up of millions of square miles of ocean, with more than a dozen countries scattered within.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has called the nearby Pacific region “our family,” although clashes around climate action have tested the relationship.

With deep geographic, cultural and historic ties, Australia is by far the largest aid donor to the region. In that vein, Seselja said that Australia plans to deliver up to 15 million Covid-19 vaccine doses there by mid-2022.

But Smith of Australian National University said the relatively sudden growth of China’s aid, trade and investment has some in Canberra speculating about what will come next from the superpower.

“I think the unease on the Australian side and among other Western powers is because the scale of [China’s] activities is far beyond what they’ve seen in the past,” he said.

“The real concern that actually keeps [some Australian officials] up at night is the possibility — as yet completely unproven — that China might decide to build a military base in the Pacific,” he said. “That would completely change Australia’s strategic environment.”

Pryke stressed that Pacific countries are fiercely protective of their sovereignty but that because the region is located between the U.S. and Asia, it’s of great geostrategic importance for other powers.

“You’ve got a pretty good data point of the Second World War to see how strategically important these small islands can be in a vast ocean, in terms of the necessity for logistic chains and for expansion of force projection,” he said.

A low point

The Pacific region isn’t the only source of tension between Australia and China, and the relationship has rapidly deteriorated in recent years.

A string of events has led to the deterioration, including Australian intelligence agencies’ early identification of Chinese tech giant Huawei as a security threat and the Morrison government’s early call for an independent inquiry into the origins of Covid-19.

Such developments reportedly angered China’s president, Xi Jinping, who has been much more forthright in pushing back against what he views as unfair depictions of his country in the West.

“Australia has really been ahead of the curve in terms of being openly critical of China. So China has singled out Australia to be punished for that kind of behavior,” Pryke said.

As a Chinese government official summed up to a reporter in Canberra late last year: “China is angry. If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy.”

The countries continue to have a strong trade relationship, but as the spat ramped up, China slapped bans and tariffs on Australian products, including beef and lobsters.

And with the latest scuffle over vaccines in Papua New Guinea, there is no sign of a thaw any time soon.

“The Australia-China relationship has really hit a low point and continues to go lower and lower,” Pryke said.

“We keep asking — where’s the bottom of this?”

Recent Comments