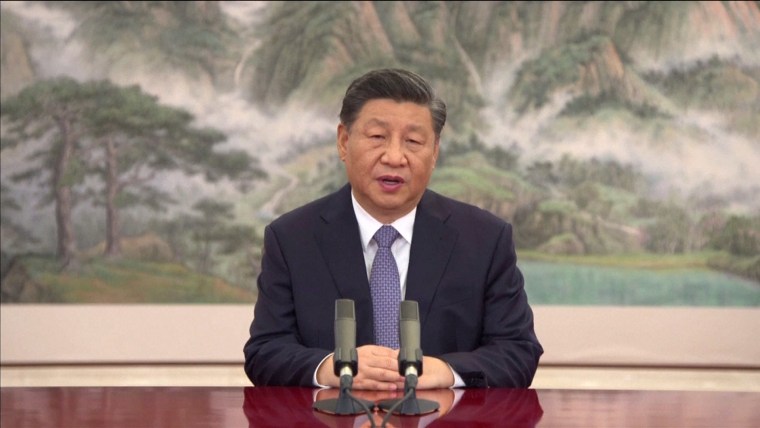

Chinese President Xi Jinping wants to dominate his country’s future. To do that, he’s putting a whole new spin on its past.

The ruling Communist Party adopted a landmark resolution Thursday that both rewrote its own history according to Xi, and elevated the president to a level only rivaled by iconic past leaders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.

Experts say the “historical resolution” will pave the way for Xi, 68, to secure an unprecedented third term in office next year — and potentially rule China for life.

The move came at the end of the closely-watched sixth plenum of the party’s Central Committee, a mostly male group of more than 300 top leaders. It is the last major meeting before a party congress next year where a decision will be made on Xi’s future.

He is only the third leader to have a historical resolution adopted during his presidency, after Mao and Deng.

This was Xi’s “attempt to further consolidate his power and to define his historical legacy in the history of the party,” said Jinghan Zeng, a professor of China and international studies at Lancaster University in Britain ahead of the plenum.

Xi’s political philosophy — called “Xi Jinping Thought” — is already being interwoven into Chinese society, added to educational textbooks from primary school to college. The historical resolution will now further entrench his personal leadership as the defining characteristic of Chinese politics for years and possibly decades to come.

In the weeks leading up to the meeting, state media praise for Xi was even more effusive than usual. A commentary in People’s Daily, the party’s flagship newspaper, called leadership the “most critical condition in the face of major historical junctures and tests.” Safeguarding Xi’s “core position” and the party’s overall authority, it said, were “the fundamental guarantees for winning new victories” in China’s modernization drive.

Mao and Deng both used their historical resolutions to criticize what had come before: Mao, in 1945, asserting his dominance as ruler at the birth of communist China, and Deng, in 1981, carefully criticizing Mao’s mistakes and paving the way for greater economic liberalization.

But instead Xi has heaped praise on his predecessors.

The plenum’s official communique said that Mao “blazed the right revolutionary path.” This is despite the millions of people who died of starvation in the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s disastrous attempt in the late 1950s and early 1960s to rapidly industrialize Chinese society, and the brutal purges of the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution.

And the plenum noted how Deng was responsible for “achieving socialist modernization” — opening up China’s economy to the world starting in the 1970s.

In all, the conclusion of the key meeting seems simple: China’s Communist Party has achieved the goals of its first 100 years; now it’s ready to turn the page to a new chapter — one defined by Xi.

Adopting a historical resolution is a clear marker that this new era has begun, experts say. And the plenum drew a clear line between the resolution and the renewed authority given to the president. Its adoption was needed to “resolutely” uphold “comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Central Committee and in the party as a whole,” it said.

The communique lavished praise on Xi for his “meticulous assessment and deep reflection on a number of major theoretical and practical questions.” This has allowed Xi to “set forth a series of original new ideas, thoughts, and strategies” on what his brand of Chinese socialism should look like in the modern world, it added.

Along with Mao and Deng, Xi has already positioned himself among the most powerful leaders in post-revolutionary Chinese history. The removal of the two-term limit for presidents in 2018 has effectively allowed him to stay in office indefinitely.

Whether that actually happens will be decided next year at the party congress, a twice-a-decade event at which China’s top leaders are appointed. In between those gatherings, the party holds seven plenums, or plenary sessions, each with its own theme.

In theory, these sessions are a chance for the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s most powerful body, to propose new policies for review. In reality, in the era of strongman Xi, they allow the president “to assert dominance” while only creating “the public illusion of collective governance,” according to a briefing by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

“Sixth plenums are not usually necessarily the most important annual meetings of the Communist Party,” said Steve Tsang, a professor and director of the China Institute at SOAS University of London. “But this particular sixth plenum is very, very important indeed.”

These plans come amid China’s surging power internationally. The country is set to become the world’s largest economy within a decade. Its coal consumption will determine the global fight against climate change. And it remains locked with the United States in disputes over everything from trade and intellectual property to human rights and the status of Taiwan.

And with Xi at its helm, China has become increasingly authoritarian, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual ranking index.

In Xi’s new era, “the goal is to create a ‘great modern socialist nation,’ as Xi has articulated, by 2035,” Andrew Polk, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said in an online presentation last month.

Whereas Deng opposed Mao’s cult of personality, Xi has accrued more personal power than any single person since the country’s founder.

Under his watch, tens of thousands of officials — including Xi’s political rivals — have been investigated for alleged corruption, China’s military has been dramatically overhauled and modernized, and the country has shifted away from low-end manufacturing and is emerging as a technology powerhouse.

In recent months, Xi has eschewed the growth-at-all-costs doctrine of his predecessors and instead focused on the slogan of “common prosperity” — going after China’s tech giants and superrich with the promise of greater income distribution.

This “isn’t about Xi Jinping being a bleeding heart” liberal, Polk added. “His thinking is that a strong country doesn’t have a huge amount of economic inequality, because that leads to divisions in the populace.”

Recent Comments