Voters in November’s presidential election will choose how the United States deals with Iran and its nuclear capabilities, according to multiple government officials and experts across the Middle East.

And as President Donald Trump’s administration is set to reimpose a “snapback” of sanctions on Iran on Saturday night, despite opposition from Europe, there are fresh concerns over regional stability.

President Barack Obama and the leaders of several other major powers signed the 2015 Iran nuclear deal — officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) — which stated that “Iran’s nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful.”

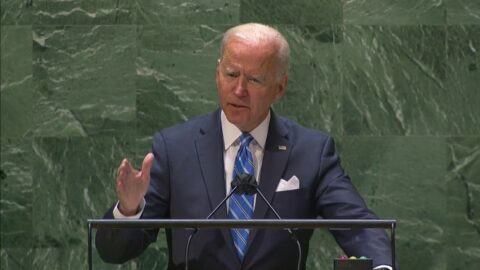

Trump, a long-standing critic of the deal, unilaterally pulled the United States out of the deal in 2018. Joe Biden, meanwhile, has been a vocal supporter of the deal he originally tried to sell to Congress, before Obama bypassed the legislature — and has called the current U.S. policy toward Iran “reckless” in a recent op-ed.

The former vice president and Democratic nominee’s broadside capped a recent round of criticism from former Obama administration officials — some of whom publicly support Biden’s presidential bid — and highlighted just how different U.S. relations with Iran could potentially be under a Biden presidency.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other administration officials have defended the current administration’s aggressive stance and have long argued that the 2015 nuclear agreement — signed by Iran, the U.S., Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France and Germany — did little to constrain Iran’s other activities in the region that threatened American security interests and those of its allies.

“The previous administration chose appeasement as the model to respond,” Pompeo said in a recent interview with Fox News, answering a question about Biden’s recent criticism.

That was in contrast, he said, to Trump’s “completely different direction” that sought to stem funding for Iranian activities elsewhere, including support for armed groups such as Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Houthi rebels in Yemen.

State Department spokesperson Morgan Ortagus told NBC News in an emailed statement that the Trump campaign of “maximum pressure” on Iran had curtailed the country’s provocative maritime behavior in the Persian Gulf, constrained the capabilities of its state broadcasting networks and deprived Tehran of billions of dollars in revenue.

All this meant Iran’s “proxies in Syria and elsewhere are going unpaid, and the services they once relied upon are drying up,” she said.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

But politicians and analysts around the Middle East are not convinced.

“The line that Trump is following is a line of escalation, and that includes the issue of Iran,” said Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, the leader of the Palestinian National Initiative political party, who served as a minister in one of the Palestinian unity governments.

He said current U.S. policies will only make the region more volatile, and have been heavily influenced by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — including Trump’s 2018 decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal.

While the so-called “Abraham Accords” signed this week provide little obvious progress in ending the decades-long conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, the U.S.’ “maximum pressure” campaign to isolate Iran is also under question and has drawn growing skepticism across the region.

“We don’t think it was quite successful,” Mona Makram Ebeid, a former senator and parliamentarian in Egypt, said in reference to the American campaign to economically weaken Tehran.

Ebeid who is now a professor of political science at the American University in Cairo said Egyptians share the view that Iran is a “big threat in the region,” particularly given Tehran’s support for Hamas in neighboring Gaza, but question why Obama’s approach was needlessly discarded.

She said that renewed American sanctions against Iran would not resolve the problem posed by the country’s nuclear program, but that the November presidential election in the U.S. could significantly change the situation.

“Biden will not want to be entangled in conflict or in solving conflict in the Middle East,” Ebeid said. “He will be more flexible towards Iran.”

“The objective of the maximum pressure campaign was to induce a change in Iran’s behavior,” Lt. Gen Jim Clapper, the former director of National Intelligence from 2010 to 2017, said, “and it hasn’t done that.”

“The Iranians didn’t suddenly become the shining city on the hill because of the JCPOA,” Clapper recalled. “By abrogating, dropping out of the JCPOA, we’ve isolated ourselves, and in my mind, lost leverage with the Iranians,” he said.

“The problem is that what elicited Iranian willingness to negotiate was that there was international pressure on them, but we don’t have that any more.”

In recent weeks, the U.S. has failed to win U.N. Security Council approval for measures designed to maintain pressure on Tehran, including an indefinite arms embargo and the reimposition of global sanctions that were lifted back in 2015 with the signing of the Iran nuclear deal.

The administration’s lead official on Iran, Brian Hook, resigned ahead of the failed arms embargo vote in August, and just days ago the International Atomic Energy Agency released a report showing that Tehran now had 10 times the amount of low-enriched uranium than was permitted under the terms of the deal.

While Pompeo said this proved the 2015 deal failed to constrain Iran, other experts are quick to point out that Iran’s expanded stockpile and other moves to break restrictions introduced by the nuclear deal are all reversible.

Two weeks ago, Iran granted IAEA inspectors access to one of two sites where undeclared nuclear activity took place in the 2000s. Inspection of the second is due in September.

According to Ernest Moniz, the former secretary of energy who helped negotiate the agreement and then sell it to Congress, the fact that verification and inspection measures are still working as intended under the deal is crucially important.

“I would be very surprised if Iran were to reconstitute a weapons program, using facilities that are inspected 24/7 by the IAEA,” he said.

And for some Iranians, a reconstituted agreement might offer the most attractive long-term solution.

“If they’re actually serious about completing their commitments under the agreement,” Foad Izadi, a professor of North American studies at Tehran University, said, “then Iran has always said that they’re open to discuss other issues that have resulted in difficulties.”

For some neighboring nations, that discussion cannot happen fast enough. U.A.E ambassador to the United Nations, Lana Nusseibeh, said she hoped any future negotiations would better address other Gulf countries’ “serious concerns about Iran’s behavior.”

“We would hope that the regional voice is represented next time around – and that would be our advice for whichever administration wins in November.”

But across the region there is anxiety, particularly in Israel and Saudi Arabia, according to Ilan Goldberg, a senior fellow focused on Middle East security at the Center for a New American Security, who worked on Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations at the Department of State and Iran’s nuclear and military capabiliites at the Department of Defense.

Countries supportive of the current approach are concerned about a change in policy if Biden wins the election, Goldberg said. And at some point, fresh talks with Tehran would have to address not just nuclear capabilities but also other regional concerns centered on Iran’s behavior beyond its own borders, he predicted.

“You can’t make an arms control deal contingent on solving all the problems in the Middle East. But you also can’t ignore all the problems in the Middle East to try and reach an arms control deal,” he said.

“I think it’s possible we’ll end up in some kind of diplomacy early next year regardless of what happens.”

Ali Arouzi reported from Tehran, Charlene Gubash from Cairo and Abigail Williams from Washington D.C.

Recent Comments