HONG KONG — When Daniel Chow left Singapore in 2020 for a job in Hong Kong, he expected that his wife and two young sons would join him as soon as the pandemic eased and the Chinese territory shifted away from its “zero-Covid” strategy.

Now Chow has moved back to Singapore after two years of frustration, citing the continued constraints of life in Hong Kong even as the rest of the world opens up.

“We decided that my family won’t move” to Hong Kong, said Chow, 43, who works in investment services. “Schools keep getting shut down, and the city has tight restrictions on movement. Kids are the ones who have suffered the most.”

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

For most of the pandemic, Hong Kong and Singapore — both densely populated Asian financial hubs with residents from all over the world — kept virus cases and deaths to a minimum with border closures, strict quarantine requirements and extensive testing and contact tracing.

But while Singapore has steadily moved to reopen in recent months, Hong Kong remains mired in restrictions that critics say are costing it business and talent, with Singapore a prime beneficiary.

Singapore was among the first countries in Asia to open its borders to the world. Travel has picked up in recent weeks as the city has done away with compulsory quarantines, pre-departure tests for vaccinated people and an outdoor mask mandate. The city of more than 5 million is reporting an average of about 6,000 cases a day.

Hong Kong, too, has moved to ease restrictions, reopening the border to nonresidents, resuming in-person classes and allowing bars and other businesses to restart operations for the first time since January.

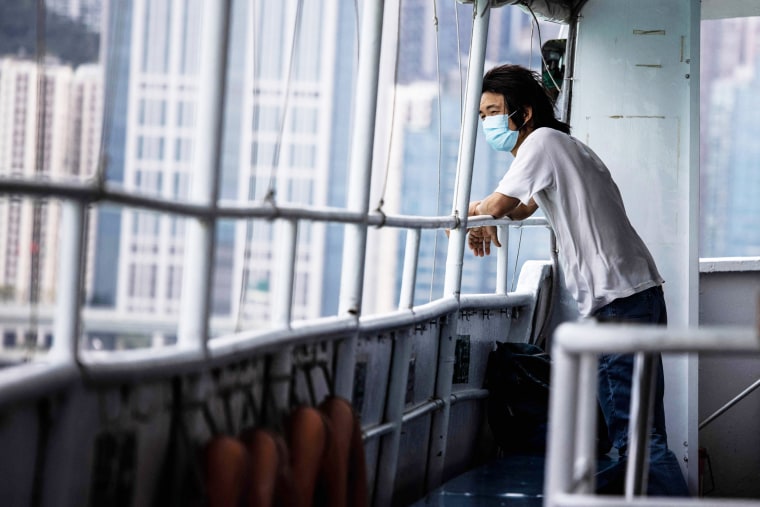

But passengers arriving from overseas are still required to quarantine in hotels for seven days at their own expense — a burden for frequent travelers like Chow, who had been returning to Singapore to see his family.

“This became a really big factor for me to leave Hong Kong and an even bigger factor compared to what brought me in in the first place, which was lots of opportunities career-wise,” he said.

Hong Kong has retained its strict policies with the aim of reopening its border with mainland China, which has taken a similar “zero-Covid” approach. But with the mainland still emerging from its worst outbreak since the start of the pandemic, that seems unlikely to happen any time soon, holding up Hong Kong’s reopening to the rest of the world, as well.

Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, said last month that hotel quarantine and testing-on-arrival requirements were “very unlikely” to be eased before she steps down at the end of June, citing the risk of new variants. The city of 7.4 million is reporting about 200 to 300 coronavirus cases a day.

Lam’s successor, John Lee, has said reopening to mainland China and the rest of the world is one of his priorities. But the city’s business community has grown increasingly impatient, with lobbying groups pressing officials to lift the quarantine requirement or at least allow travelers to quarantine at home.

“Being able to resume travel is of the utmost importance, whether it is with the mainland or with foreign countries,” Betty Yuen, the new chairwoman of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, told local broadcaster TVB last month. “Our strict restrictions have made us almost like a sequestered island.”

The travel restrictions have also wreaked havoc on flight schedules in and out of Hong Kong, which once had one of the busiest airports in the world. Only 126,000 passengers passed through Hong Kong International Airport in April, compared with 6.5 million in April 2019.

Willie Walsh, the director general of the International Air Transport Association, told reporters in Singapore last month that it would take years for Hong Kong to recover as a global aviation hub.

“That opportunity is going to go to other airports in the region,” he said. “Singapore will clearly, I think, benefit from that.”

Singapore’s pandemic restrictions have also weighed on its population, with some foreign residents citing them as among their reasons for leaving. But the government has emphasized the importance of reopening the economy throughout the pandemic, said Teo Yik Ying, a professor and the dean of the School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore.

“In comparison, I think that has not been easy for the Hong Kong government to decide unilaterally,” he said, given that its pandemic policy is tied to mainland China’s.

The Singaporean government has also been lauded for its communication with the public during the pandemic, which Ying said engendered trust.

That level of trust is lacking in Hong Kong, where antigovernment protests in 2019 were followed by a sharp crackdown on dissent. During the pandemic, the government has been criticized for inconsistent messaging and reactive measures.

Talk of leaving Hong Kong reached a fever pitch this spring as the city experienced its worst outbreak of the pandemic. Rumors of a full-scale lockdown, and especially fears of children being separated from their parents by quarantine policies, spurred thousands to leave, at least temporarily.

Singapore is a natural alternative, especially for those in financial services. But there are also obstacles to moving there, leading some Hong Kong businesses and families to rethink their plans.

The city recently tightened its work visa requirements for foreign nationals because of worries they would take jobs away from Singaporeans.

“Everyone here welcomes expatriates and foreign business to Singapore, but the key is they have to add value to the local economy and for locals,” said Walter Theseira, an associate professor of economics at the Singapore University of Social Sciences business school.

Property prices were rising in Singapore even before the influx from Hong Kong, which has also driven a surge in demand for places in private schools.

“It would be a concern for families trying to move here, because I have heard that people cannot get slots in schools,” Theseira said.

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong says the city welcomes the existing competition from Hong Kong, which he says makes for “a vibrant, dynamic region.”

“We are happy to welcome them, but actually we would be more pleased if they were happy to remain in Hong Kong,” he told The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board in April.

Ying is hopeful that Hong Kong will soon open up to the rest of the world.

“Hong Kong is not just important to itself or for China, but it’s strategically important as an economic and transportation hub for this part of the world,” he said. “When Hong Kong’s economy suffers, this entire region suffers, as well. So it is to everyone’s advantage that Hong Kong is able to resume its status as an economic center in Asia.”

Recent Comments