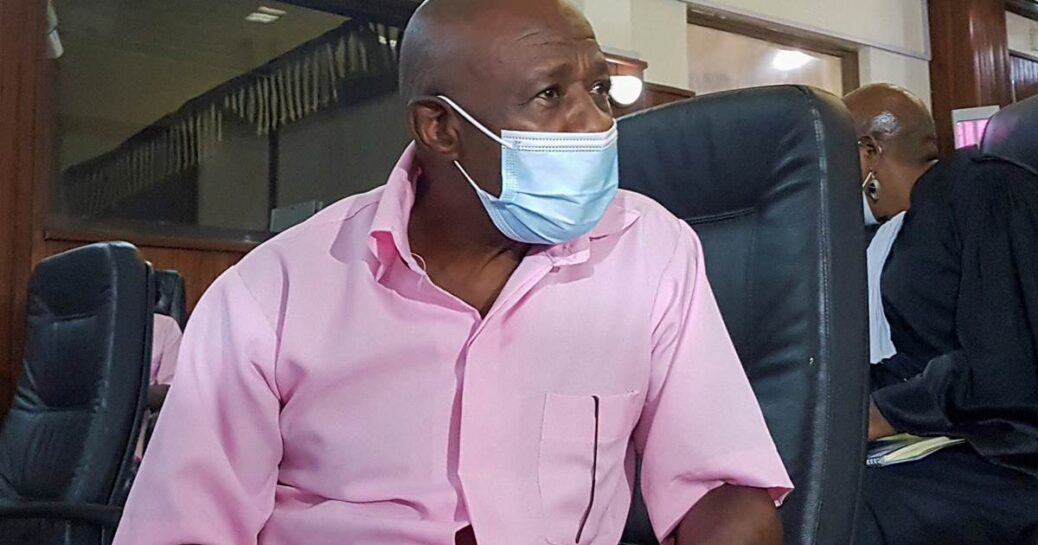

The Hollywood film “Hotel Rwanda” brought international praise to Paul Rusesabagina for saving hundreds of lives during the 1994 genocide in the central African nation, but in his home country, he’s now being tried as a terrorist.

A fierce critic of Rwanda’s powerful president, Paul Kagame, Rusesabagina, 66, had been living in Belgium and the United States for the past 25 years. He was lured back to Rwanda last year, however, where he was arrested and charged with financing terrorism, arson, armed robbery, abduction and murder. If convicted, he could be sentenced to more than 20 years in prison.

“As President Kagame’s best-known critic, Paul Rusesabagina posed a threat to his international image,” said Timothy Longman, professor of political science and international relations at Boston University.

The State Department, which has previously criticized Rwandan authorities for not following due process, has urged the government to respect the rule of law and ensure that Rusesabagina is treated fairly.

“We are very concerned about public statements, including from some Rwandan authorities, that correspondence between Rusesabagina and his lawyers has been intercepted,” a State Department spokesperson told NBC News after leaked video from the Ministry of Justice showed Rusesabagina’s communications had been accessed by prison officials. “We urge the Rwandan government to be fully transparent about both the means and the legal basis for how Mr. Rusesabagina arrived in Rwanda.”

Congressional leaders have also raised concerns about the case, sending a bipartisan letter to Kagame asking for Rusesabagina to be returned to his family. Last month the European Parliament voted for an investigation into Rusesabagina’s arrest as well.

On March 12, Rusesabagina said he would no longer attend the trial because his “basic rights were being denied.” Rwandan prosecutors, however, said the evidence against him is strong.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

Rusesabagina and Kagame both rose to prominence for their heroics in 1994, when extremist Hutus targeted the ethnic minority Tutsi population, resulting in over 800,000 deaths.

Western countries did little but evacuate their own nationals.

While managing the luxurious Hotel des Mille Collines, Rusesabagina used top-shelf liquor and Cuban cigars to distract extremists from murdering Rwandans posing as his guests.

“If you stay friendly with monsters you can find cracks in their armor to exploit,” Rusesabagina wrote in his 2006 memoir, “An Ordinary Man.”

Meanwhile, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by Kagame, liberated the capital, Kigali, ending one of the bloodiest 100-day stretches in modern history.

The RPF has held power ever since. Under Kagame, who became president in 2000, the former Belgian colony has seen rapid development through foreign investments from companies and organizations such as Starbucks and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

But human rights groups have criticized Kagame for stifling political debate. Freedom House, a U.S.-based human rights group, said Rwanda has a history of pervasive surveillance and suspected assassinations, a pattern that has led countries such as Sweden and South Africa to expel Rwandan diplomats.

“While Kagame can be praised for many things, particularly his good economic management, he has been extremely intolerant of criticism,” Longman said.

Rusesabagina’s star would rise when Don Cheadle’s portrayal of him in the 2004 film “Hotel Rwanda” was nominated for an Oscar, launching him to the red carpet next to Angelina Jolie.

He has seized his public profile as an opportunity to criticize Kagame.

In 2017, Rusesabagina mobilized the Rwandan Movement for Democratic Change, or MRCD, a coalition of exiled political parties that opposes Kagame and has called for more democratic freedom in Rwanda.

In a video that year, Rusesabagina urged supporters to use “any means possible to bring about change in Rwanda.”

Now, prosecutors have linked those words to a series of attacks in 2018 and 2019 by the MRCD-backed National Liberation Front in Rwanda’s Nyungwe Forest, which resulted in nine civilian deaths.

Rusesabagina’s family has called the trial a “sham” and said he had no command over the National Liberation Front.

But prosecutors have laid out an extensive indictment against Rusesabagina and 17 co-defendants, including a 2011 wire transfer allegedly sent from Rusesabagina to a rebel Hutu commander, which they say the Justice Department authenticated.

NBC News was not able to confirm these claims, and the Justice Department declined a request for comment.

Belgian police also raided Rusesabagina’s Brussels home in 2019 and seized computers, phones and documents, which Rwandan prosecutors say contain evidence of Rusesabagina’s connection to the National Liberation Front.

The circumstances of Rusesabagina’s arrest have also caused controversy.

According to recent trial testimony, Rwandan authorities tricked Rusesabagina onto a private plane after a flight from Chicago to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, in August with false speaking offers in Burundi.

The flight landed in Rwanda instead, where Rusesabagina was arrested and did not appear in public for days.

His family describes it as a kidnapping, but Kagame denied wrongdoing during an appearance on state television in September, calling the operation “flawless.”

Rusesabagina’s international defense team, whom he is barred from speaking with, says the Rwandan government should have requested his extradition diplomatically.

“We are scared he is going to die in prison,” said his daughter Anaise Kanimba, citing health concerns for her father. “The Biden administration should stop believing that a fair trial is possible.”

Rwandan Prosecutor General Aimable Havugiyaremye said Rusesabagina’s right to a fair trial is protected and the proceedings are “being conducted openly and transparently.”

Recent Comments