They extol the then-Soviet Union, even under Joseph Stalin — whose image as a brutal dictator has been rehabilitated under Putin — and paint its collapse as a great tragedy, just as Putin does. The Russian leader is presented as a man who saved the country from the ruins and is now left defending it from the same enemies who threatened the USSR, she said.

“And with that the children are led” to “the propaganda that hits you in the nose,” said Eidelman, who left Russia after the invasion and now lives in Portugal.

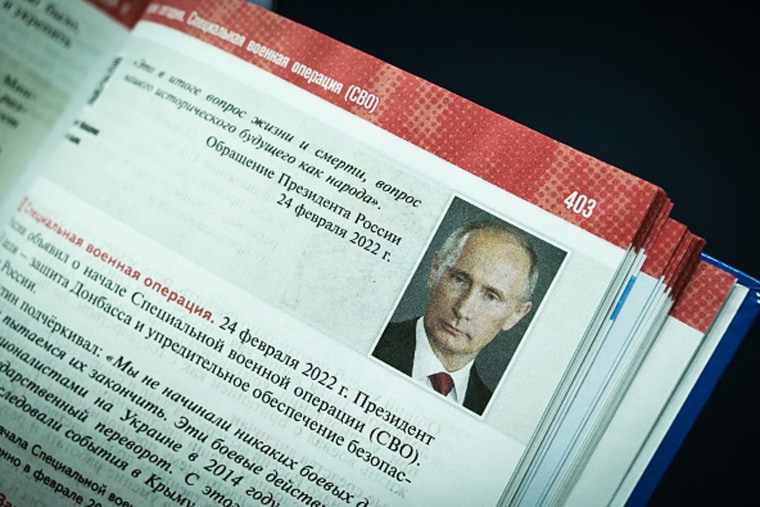

The chapter on the war in Ukraine repeats the Kremlin narrative that it had to attack its neighbor to avoid Ukraine joining NATO and risking a broader conflict.

“It would perhaps be the end of civilization,” the textbook says. “It could not be allowed.”

It accuses the West of instigating the war and trying to destroy Russia economically, while reiterating the existence of Ukrainian neo-Nazism. The chapter also features profiles of Russian soldiers who fought or died in combat, but doesn’t mention how many have died.

Students are cautioned against consuming online information about what is happening in Ukraine to avoid being “manipulated” by what it calls a “global industry” of fakes.

“This has nothing to do with history. It’s hardcore propaganda, Soviet-era style,” said a former history teacher, who did not want his name published over fear of repercussions for his family still in Russia.

He said he was “in shock” after reading the textbook, whose tone often matches that of Putin’s speeches.

“It’s not just an attempt by the Kremlin to influence young minds, but pure indoctrination of the young generation,” said the teacher, who left Russia late last year and now teaches in another country. “It’s their way to form a society loyal to Putin.”

Drawing a line

The authors, who include Putin’s aide and former Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky, readily admit that the textbook is a reflection of the Kremlin’s view of history.

“The textbook presents the point of view of the scientific community through the prism of the state position on current events,” Medinsky told a news conference presenting the new textbook in Moscow last month.

The goal of the textbook was to “teach students to think” Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov also said at the event.

But Eidelman said it fails badly at that, because it gives only one point of view.

In previous years, there were multiple textbooks that a teacher could choose from, said Nikita, a history teacher from St. Petersburg, who wanted to be identified only by his first name out of fear he could lose his job and concerns about his family’s safety. Some of them even contained opposing views from historians, exposing students to a plurality of opinions, he said. The new textbook contains only one such section — on the legacy of Stalin.

It does not pose questions, Nikita said, instead “immediately answering them without allowing one to argue.”

Putin has used his interpretation of Russia’s imperial past as a pretext for invading Ukraine — a subject on which Pope Francis sparked anger last week. So a modified syllabus was a natural next target, Nikita said.

“I would have been surprised if this kind of textbook was not created,” he added.

Ukraine decried the use of the new textbooks in occupied regions, accusing Russia of “using education as a weapon.” The new textbook is “a new level of militarization of education and propaganda of war among children,” Ukrainian human rights ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets said.

The war has taken a harsh toll on the education of Ukrainian children. UNICEF reported Tuesday that “children across Ukraine are showing signs of “widespread learning loss.”

Denis Kotenko, a history teacher in the Siberian city of Barnaul, said in an interview that he considers the new textbook to be an “achievement” in many ways — using QR technology to link out to archival materials, refocusing substantially on modern history and balancing between acknowledging both the good and the bad during complicated periods of Russian history.

The history textbooks of his youth seemed like they “forced Russian people to repent” and feel “ashamed” of their Soviet past, said Kotenko, 35, who has taught history for 11 years. “There is nothing of this in the new textbook. It’s an achievement. It’s good. It draws a line well,” he added.

He admitted some sections seem politicized and that the textbook gets “carried away” in its language at times, but he said it was “unavoidable” in the current geopolitical climate.

Russia is, of course, far from the only country to have politics influence how history is taught in classrooms.

The teachers told NBC News that many other countries approach teaching history from a nationalist or imperialist perspective, and absolute neutrality is impossible because people, not robots, write history textbooks.

No country looks at history objectively, but this is different because “what they are doing is they are saying — it’s either this or prison,” said Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at the New School in New York and the great-granddaughter of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, whose time at the helm is also profiled in the textbook.

”That makes it a Stalinesque version of history,” she said.

Eidelman said she was worried about her colleagues remaining in Russia who might share her moral opposition to the new textbook, leaving them “in the most difficult circumstances.”

The history teacher who left Russia last year and wanted to remain anonymous also said he feared many would have to swallow their professional pride, unless they are willing to risk getting fired or prosecuted.

“There are fewer and fewer teachers who are ready to go against the system,” he said. “Many have left the country, and those remaining are just really afraid.”

OVD-Info, a Russian organization that tracks political and war-related persecution, has been documenting cases of Russian teachers being fined, fired or even criminally charged for expressing views that did not coincide with the Kremlin’s narrative on Ukraine in their classrooms. Some have been reported to authorities by their own students.

Still, the teachers said a textbook is just a study guide, and a good teacher can shape what is going on in the classroom. Some pointed to an old Russian adage for teachers: “Write down a lesson plan, and the rest is up to you.”

Those still in Russia said they planned to use the textbook as loose guidance while encouraging discussions in their classrooms.

“The teachers who understand what this is all about will drop the politics,” said the teacher who has fled, “and just teach historical facts instead of the propaganda.”

Recent Comments