Swapping out price tags for antiwar leaflets, wearing green ribbons, flashing a copy of Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace.”

Those are things that can get ordinary Russians who don’t agree with the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine detained, fined or even jailed.

Since the start of Moscow’s incursion, media in Russia have been cautioned against calling it a “war,” and new draconian legislation has been put in place to stop people from “discrediting” the Russian army, punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

That has meant the few Russians who still dare speak up against the war have gotten inventive to escape arrest. But it’s far from guaranteed.

Artist and musician Alexandra Skochilenko, from St. Petersburg, has been in detention for nearly two months after replacing several price tags at a local supermarket with small pieces of paper containing messages about the Russian army’s actions in Ukraine.

One of them read: “The Russian army bombed an art school in Mariupol. About 400 people hid in it from shelling.” Another said: “Putin has been lying to us from TV screens for 20 years. The result of this lie is our willingness to justify war and senseless deaths.”

Skochilenko’s lawyer, Yana Nepovinnova, told NBC News that Skochilenko’s act of protest was caught by a customer, who raised a complaint.

Skochilenko, 31, is now facing criminal charges of spreading “deliberately false information” about the Russian army and could face up to 10 years in prison, Nepovinnova said. Skochilenko has admitted to swapping the price tags, but she denies that she was spreading false information, according to her lawyer. Her detention has been extended until at least July 1.

“I feel like they came into our home and took my family away because of some price tags,” Sofia Subbotina, Skochilenko’s partner, said on the phone from St. Petersburg, sounding dejected. “Ten years is a monstrous term. They sentence people to less for murder.”

Nepovinnova said she fears Skochilenko’s case will be used to send a “clear message” to others who dare speak up that they will face the same fate.

“She is essentially behind bars for her words,” Nepovinnova said.

During the decades of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s crackdown on dissent, political protest in Russia has become nearly obliterated. Still, in the first days of the war, thousands of Russians took to the streets to voice their opposition. But that has largely fizzled out amid police violence, mass arrests and the Kremlin propaganda insisting most Russians support Moscow’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. What continues are the one-person protests of all shapes and forms to get one message across: There are people in Russia who do not agree with the war.

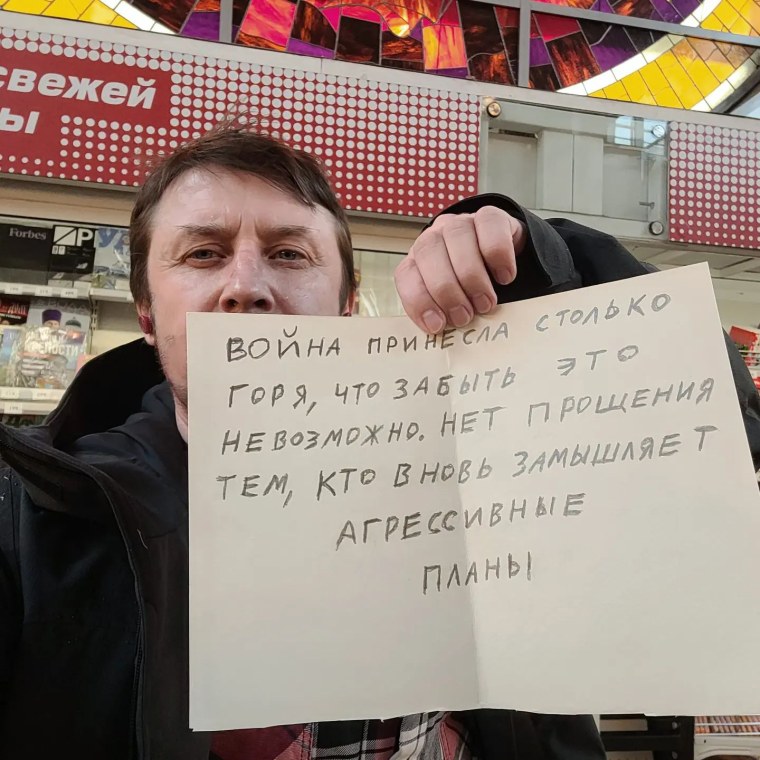

Another St. Petersburg resident, Artur Dmitriev, said he was detained in early April for holding up a sign that read: “The war has brought so much grief that it is impossible to forget. There is no forgiveness for those who are making aggressive plans again.”

This anti-war message was, in fact, an abbreviated direct quote from a speech made by Putin last year on the day Russia celebrates victory over Nazi Germany.

This made no difference to the authorities.

After spending 24 hours in detention, Dmitriev, 43, said he had a court hearing and was found guilty of “discrediting Russian armed forces,” according to the court papers he showed NBC News, under the newly enacted legislation. He said he was fined 30,000 rubles, or $520.

Holding up his court papers in a Zoom video, Dmitriev said his guilty verdict proves the absurdity of the system that detained and fined him for using Putin’s own words.

He said he even sent a snarky email to the president’s press office, asking the Russian leader to split the fine since they were now “accomplices.” The office responded but essentially ignored his request, Dmitriev said.

He admitted he was afraid throughout the ordeal and even more so now that he’s on law enforcement’s radar. But he said it’s important to speak up.

“It’s obvious where we are headed. It’s classical Orwell,” Dmitriev said. “If you are standing aside, you are only making it worse. But if you do this, you are letting people know that they are not alone.”

Making sure others don’t feel isolated is also close to Mikhail Podivilov’s heart.

That’s why the IT specialist stood with his bank card above his head at a Moscow metro station one evening in late March, hoping others would take notice, he said.

Written on his card was the word “Mir,” or “peace,” in Russian. (“Mir” is the name of a payment system used by Russian banks, and many bank cards feature it prominently.)

Within five minutes, he was being questioned by police, Podivilov, 22, said.

Speaking with NBC News via Zoom from his home in the suburban town of Ozyory in the Moscow region, Podivilov said the police officers wrangled with him for nearly an hour, trying to get him to move. He refused and all the while stood there with his card above his head, his feet and hands freezing on a chilly Moscow evening, Podivilov said. In the end, they let him go.

Podivilov said he was surprised to just walk away. But despite the fear of arrest, he said he does not have “a moral right to be afraid.”

“In Ukraine, that’s where people can be afraid,” Podivilov added, with no hesitation in his voice. “The maximum that can happen to me is I will get jailed.”

OVD-Info, an independent Russian organization that tracks political persecution and freedom of assembly violations, maintains a long tally of names and acts of Russians who have stood up against the war, including by displaying the blue-and-yellow colors of the Ukrainian flag, standing with a copy of Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” in Red Square, holding up banners with nothing but eight asterisks (corresponding to the letters in the slogan “No to war” in Russian), and even wearing green ribbons, which have become a symbol of opposition to the war.

It estimated that as of early June, more than 16,000 people had been detained over anti-war protests. It said there are nearly 2,400 court cases underway for allegedly “discrediting” Russian armed forces under the newly enacted legislation, and that it’s aware of at least 170 suspects facing criminal charges related to speaking out against the war.

But for the millions of others who remain silent, the fear is too much to bear, said artist and activist Eugene, who said he did not feel safe revealing his last name.

Eugene, 31, offers an opportunity to those who want a chance to say something against the war to do so anonymously.

Since March 20, he has been running an Instagram account called Malenkiy Piket, or Little Protest in Russian. It’s meant to be a safe space where people can send in photos of small figurines, perhaps a representation of themselves, made out of plasticine or Legos, that are holding up peace messages. The figurines are discreetly placed around people’s towns and cities, or, if it feels too dangerous, in the safety of their homes.

The account’s feed is full of colorful photos of figurines, often dressed in Ukraine’s blue-and-yellow colors and placed against city monuments, benches, riverbanks or people’s kitchen tables, with signs reading, “No to war,” “Ukrainians forgive us,” and “Why?” Their might goes beyond their size, emblematic of how much space is left for freedom of expression in Russia.

For Eugene, it allows ordinary Russians who, over the decades of Putin’s rule, have lost the ability for political thinking to “exercise their political bodies,” he said, speaking via Zoom from his dimly lit St. Petersburg flat. Malenkiy Picket is like a training ground for what it’s like to still speak up when fear is omnipresent, he added.

Eugene said he knows he is risking his freedom by running an account that gives people a platform to speak up, even if it’s in the most discreet of ways.

“Some days I’m scared; others, I’m not,” he said.

Aware of the risks, he said he made sure Malenkiy Piket would keep running and posting, even if he was detained. He said he believes things in Russia are about to get a lot darker before they can get better, but he is not planning to give up fighting for freedom of expression and against the war.

“Even if tomorrow is the end of the world, I should still try to do something,” he said with a smile.

Recent Comments