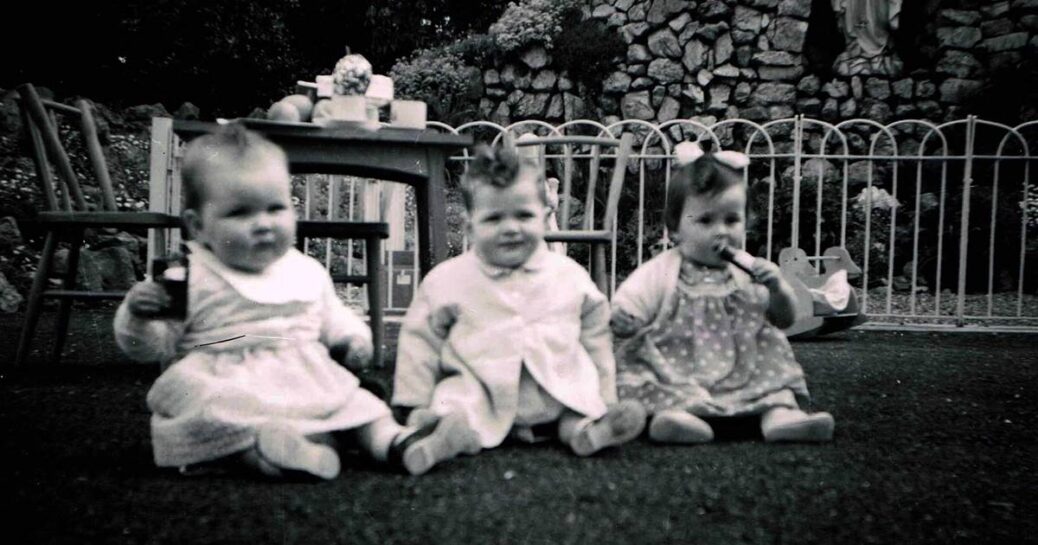

Four decades after she left the Bessborough mother and baby home in Cork, Ireland, Mari Steed made a horrifying discovery. While there as an infant, she had been part of what she calls a “highly unethical” vaccine trial.

Starting at 5 months old, Steed was vaccinated at least three times with an experimental shot to prevent diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus and polio, her medical records, which she shared with NBC News, revealed. Steed, now 60, later learned the vaccine was administered without the knowledge of her birth mother, with whom she lived for the first 18 months of her life at Bessborough.

At least dozens of other children at mother and baby homes —the since-shuttered, church-run institutions in Ireland for unwed women and their children — were allegedly part of such trials during the same time period. Like Steed, others who reunited with their birth mothers learned there had been no parental consent for their participation, either.

“Scientifically, I understand that there is no more perfect research group than a group of captive children. But that requires enormous ethical protocols, and that just wasn’t followed,” Steed, who was adopted from Bessborough by an American family, said. “Whether that was through sheer ignorance or ‘We don’t give a crap what happens to those kids’ — that part of it still makes me angry.”

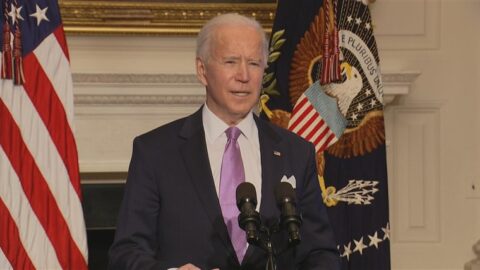

On Tuesday, Ireland’s Commission of Investigation Into Mother and Baby Homes and Certain Related Matters released a long-awaited report on various abuses that occurred in the homes. The report found some 9,000 children had died in the church-run homes, while unmarried mothers were subjected to verbal and physical abuse.

It also outlined details of some seven vaccine trials that involved “a number of children,” taking place from 1934 to 1973.

The homes became the subject of a yearslong investigation after the 2014 discovery of an unmarked mass grave at another Irish mother and baby home in Tuam, in County Galway, where almost 800 children died from 1925 to 1961.

Six interim reports from the commission have been released. In those, the commission concluded that many of the children died of malnutrition and other preventable diseases; sometimes, their bodies were sent to universities for anatomical studies.

The final report, particularly any details on the vaccine experimentation, is “long overdue,” said Steed, who now lives in Ruther Glen, Virginia, and works at a day spa after careers in banking and academia. She has made it her life’s work to shine a light on the inhumane practices suffered by Irish unmarried women and their children.

Steed is hoping anyone still alive who was involved with the vaccine trial, including researchers, pharmaceutical employees or the nuns who ran Bessborough, will be held accountable.

Their overarching offense, she said, was treating residents of the homes as “less than the rest of society” — which has left many survivors, such as herself, with lasting emotional scars.

“In Ireland at that time, it was just deemed acceptable,” Steed said. “If you were an unmarried woman or the child who was the product of a nonmarital relationship, you were ‘othered,’ because that’s what the church taught people to do.”

The vaccine she received was produced by Burroughs Wellcome, a pharmaceutical company that later merged with GlaxoSmithKline. Steed confirmed through a freedom of information request with GlaxoSmithKline in 2011 that she had received the shot; she shared the confirmation she received with NBC News.

A nation faces its shameful past

Steed found out that she had been in the trial when she started searching for her medical records in the 1990s.

Records show she received her last shot shortly before she was sent to her adoptive family in Philadelphia in late 1961. The family had no idea she had been in the vaccine trial, she said.

GlaxoSmithKline declined to comment on individual records and would not comment on the investigation before the release of the report, but told NBC News in a statement that it “cooperated fully with the Commission and provided copies of relevant documents from its historic archives.”

Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, the Roman Catholic order that ran the Bessborough mother and baby home, said it also had cooperated with the commission in passing information along. They declined to comment on the individual allegations.

As for the vaccine trial, the Sisters said in an email to NBC News that they had “no information to support the assertion being made in your query.”

Steed does not believe she suffered any physical effects of the trial that she endured. In 2014, a doctor who oversaw trials at mother and baby homes claimed that the vaccines did not harm any children involved; NBC News could not verify that claim.

The allegations about the homes run by nuns have caused deep shame for a country steeped in Catholicism. While the commission does not have the power to award financial compensation to victims or their families, many are hoping the Irish government will take action.

“The first step from the government has to be to provide full access for individuals to their own information,” said Maeve O’Rourke, a lecturer in human rights at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and co-director of the Clann Project, a pro bono initiative that has gathered evidence for the commission and advocated on behalf of the mothers and their children.

“People have the right to the truth — the right to know who they are, what happened to them, what became of their disappeared relatives. This is the absolute basic requirement that the government must fulfill before any other form of redress can have meaning or sincerity,” she said.

The commission has focused on the history of 14 mother and baby homes and four county homes in Ireland from 1922 to 1998. All closed prior to the start of the investigation.

Steed said she feels she was a “guinea pig” and is furious that her birth mother, Josephine Bassett, was never told about the trial.

Bassett gave birth at age 26. When Steed reunited with Bassett in 2002, Bassett told her she felt forced to choose adoption — but begged the nuns to send her little girl to an American family so there would be less chance of Steed ending up on the fringes of Irish society like she had. Steed and Bassett enjoyed a close relationship until Bassett’s death in 2013.

It is unclear whether any of the interim reports from the commission have resulted in charges. Steed hopes Tuesday’s final report will.

“If there are living persons that can be held accountable for crimes, I hope they are appropriately prosecuted, punished, and that they are not let to get away with it again because they are nuns or priests or members of government,” she said.

Recent Comments