When Patricia Whalen first started helping Afghanistan’s female judges leave the country just a few days before the fall of Kabul, she was mostly worried about visas and seats on airplanes.

Now, Whalen, a retired Vermont family court judge, is most worried about getting them inside the airport and away from the Taliban’s guns. She fears they’re running out of time. The Taliban has warned that the Aug. 31 deadline to withdraw U.S. troops is a “red line.”

“We could have all the planes in the world land at that airport, but getting to the tarmac is almost impossible,” she said.

Whalen, who also served as an international judge in the war crimes chamber of Bosnia-Herzegovina from 2007-2012, is part of a small group of judges spread out across the world who are working feverishly to evacuate about 250 female judges and their families from Afghanistan. Having spent years on the front lines of Afghanistan’s efforts to establish a judiciary and clean up corruption, many of the judges have already received death threats either from the Taliban or people they sentenced.

“The Taliban are searching for judges door to door,” said a female judge in the western province of Herat, who did not want to be named because she is afraid of the Taliban. “We are in danger.”

The judge, 31, said she has not slept at home since the militants took Herat on Aug. 13. Nor has she gone to work, fearful that the Taliban would turn her away or worse.

“Their idea is that women can’t be judges at all,” she said.

Whalen, who is in touch with some of the judges, said her small group has been working with a wide range of people in and outside Afghanistan, including other judges, foreign ministries, congressional staff, nonprofit organizations and even a small number of people inside the airport who are helping them. She declined to name specific people for fear of putting her network in jeopardy.

When they do find seats, it’s the start of a scramble. Whalen will get a call that immediately sparks a race of logistics: what information is needed, whether they can travel safely to the airport, which gate they should go to and even what they should bring. They will need enough food and water to last for waits at the airport that can be as long as 24 hours.

“Today the first thing I heard was we had 50 seats on a plane: ‘You need to get 50 names together,’” she said Sunday.

The U.S. evacuation effort is ongoing. The U.S. government is utilizing commercial airliners to help, but one diplomatic cable seen by NBC News detailed a situation in which the Afghan staff of the U.S. Embassy was losing faith. A deadly firefight near the airport on Monday left one Afghan soldier dead and three others injured.

The judges face a particularly challenging series of hurdles. Many of them participated in some training in the U.S. including with Whalen, but they were not paid by the U.S. government. It’s a distinction that Whalen said means they don’t necessarily qualify for expedited evacuations.

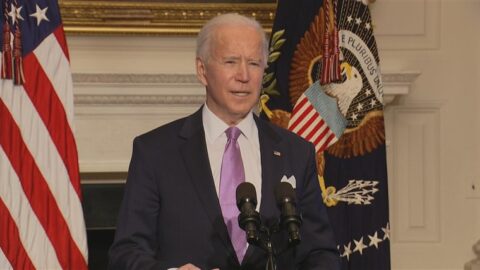

As the militants struggled to consolidate control over Afghanistan, resorting to violence to do so, U.S. senators called on the Biden administration to do more to get these women — and other female Afghan leaders — out of the country. In a bipartisan letter, 46 senators urged the administration to create a humanitarian parole category specifically for female leaders, activists and human rights defenders, among others, to allow for fast relocation to the United States.

“We are gravely concerned about the safety of women leaders, activists, judges, parliamentarians, and human rights defenders,” the letter read. “We and our staff are receiving regular reports regarding the targeting, threatening, kidnapping, torturing, and assassinations of women for their work.”

Judges that stay in the country face an intense risk of violence. Two were killed in January in an ambush as they were driving to work. Whalen said the threats have already started.

It’s possible female Afghan judges and lawyers could be eligible to leave the country via what is known as the Priority-1 program by virtue of their circumstance and need for resettlement. The State Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Lisa Walsh, the North American regional director of the International Association of Women Judges, has also been part of the effort to evacuate the women. Walsh said the judges have been receiving so-called night letters — a common Taliban tactic for threatening violence — at their homes.

Walsh, who is also a judge in the Miami-Dade County Circuit Court, said one letter the group had translated to English told a judge that she had violated Shariah and Islamic law and that the punishment was death, which could be avoided if she participated in jihad against Americans and atheists.

Taliban representatives have claimed the group has changed its ways and some rules, which included bans on women attending school or having jobs. That message has been contradicted by growing reports of violence.

A Taliban spokesman denied their involvement in any door to door search for the former officials of the Afghan government, saying they had announced general amnesty and they were still standing by it.

He didn’t answer when asked if they would allow female judges in Afghanistan.

The Taliban spokesman said the group would not yet share details about their proposed Islamic Sharia government in Afghanistan, adding that they would take all stakeholders into confidence before deciding the government.

The Taliban have shared scant details on how they plan to govern Afghanistan, instead issuing ambiguous statements that the country will be governed under Shariah. In the past, Taliban leaders have repeatedly said there is only one version of Shariah and that the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was not truly Islamic because it was not based on Shariah.

That assessment is rejected by many religious and legal scholars who say there are a range of possible interpretations of Islamic law, none of which can claim exclusive legitimacy. Many Afghans point out that the Islamic Republic’s laws were based on an interpretation of Shariah.

“No law shall contravene the tenets and provisions of the holy religion of Islam in Afghanistan,” the republic’s constitution reads.

The school of Islamic jurisprudence that the Taliban follow allows women to serve as judges in certain cases, according to Haroun Rahimi, an assistant professor of law at the American University of Afghanistan.

Despite this, the Taliban didn’t allow women to be judges or lawyers under their strict rule between 1996 and 2001 and often justified that based on Afghan culture and a sexist belief that women are unable to control their emotions, he said. Based on their interpretation of Shariah, the militants also concluded that a woman’s testimony in court counted for half a man’s, he added, though in reality they may have been ignored completely.

Afghan judges and prosecutors are preparing to watch the Taliban roll back the progress they made in the 20 years since the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, toppling the Taliban government for harboring Al Qaeda leader and 9/11 architect Osama bin Laden.

Khalili, a female prosecutor who did not want to give her full name out of fear of the Taliban, said she had dedicated her career to fighting against gender-based violence in Afghanistan. Violence against women is a huge problem in Afghanistan that U.S.-backed governments also failed to address, according to Human Rights Watch.

Khalili, 27, said she had been encouraged, however, to see more women using the justice system to protect their rights in recent years. But under the militants, she said, she expects harassment of women to get worse and the Taliban to halt any work aiming to eliminate abuse.

As the first female prosecutor in her province, Khalili said her family was repeatedly threatened by the militants. In the end, she said her mother was killed and her brother was attacked by them in part, she believes, because of her job.

“They will kill, I’m sure,” she told NBC News by telephone from Kabul.

But it’s not just the Taliban these women are afraid of. They also fear retribution from the men they put away in prison, who may have been set free as the militants marched through the country.

“They know the prosecutor, they know the judges — they know us, and now they are free,” said Khalili of the men she had prosecuted. “They can use this situation if they want to take their revenge.”

Whalen said the effort to get the judges out has become a full-time project. She works about 20 hours a day alongside four other judges, two of whom are in Australia and New Zealand. (She refers to them as the night crew.)

Together they’ve put together enough resources and connections to create a lifeline. The group has been able to get some judges and their families out of the country, though she declined to say exactly how many or where they’ve gone out of ongoing security concerns.

“Not enough,” Whalen said.

The groups communicate primarily over WhatsApp, trying to provide as much immediate guidance as possible on where they need to be and when. But the situation is still dire. Judges have relayed scenes of mobs of people at the airport and beatings by the Taliban that sometimes force them to return to their homes.

Whalen said they need the U.S. government to make a special effort to help these women.

“If we had three months, it would still be hard, but at least we could,” she said. “We don’t have time.”

Recent Comments