“Iran understands it’s relatively weak in the region, and so it had to make sure that whatever action it took was sufficiently significant to send a very strong message but not so successful that it would invite retaliation not only from Israel, but from Israel’s allies,” Rodger Shanahan, a Middle East analyst based in Australia, said in a phone interview Monday from Lebanon.

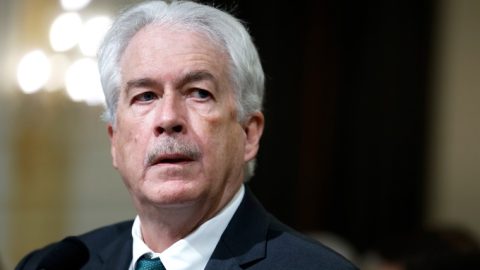

William F. Wechsler, senior director of Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council, an international affairs think tank, similarly argued that the nature of Tehran’s retaliatory mission was telling.

“Iran sent an unmistakable signal that it wanted to avoid a further escalation that could spark a truly regional war,” Wechsler said in an analysis. “It chose long-range attacks that could be readily thwarted by known Israeli defenses and pointedly did not target any U.S. facilities.”

Tehran — which does not officially recognize Israel’s existence, has long championed the Palestinian cause and celebrated Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack as a “victory” — worked to frame its weekend strikes as a “legitimate” and “responsible” reaction to Israel bombing its consulate in Syria. The West should be “grateful” for Iran’s restraint, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Nasser Kanaani said on Monday.

Yet some in Tehran have described the Saturday attack in more drastic terms. “We have decided to create a new equation” with Israel, the chief of the country’s Revolutionary Guard Corps said.

Israel has battled its arch-enemy Iran through clandestine operations and proxy forces, as well as warning Tehran over its intentions as it develops its nuclear programs. (Iran has long insisted that its nuclear program is peaceful — a claim Israel rejects.)

Through its proxies, most notably Hezbollah, the powerful and well-armed political party and militant group in Lebanon, Iran has struck at Israel. But before Saturday, neither side had openly and directly attacked the other at home.

“The region is entering uncharted territory where the previous strategic paradigm and rules of engagement no longer apply,” Amal Saad, a lecturer at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, said in a post on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. “Regardless of what Israel does next, there is no going back to the status quo ante,” Saad said in a subsequent post.

Western leaders nonetheless appear eager for Israel to show restraint in its response.

U.S. officials told NBC News that Washington was concerned that Israel could respond quickly without thinking through the potential fallout, and Biden told Netanyahu that the U.S. will not participate in offensive operations against Iran, a senior administration official said.

Iran has long viewed its missile arsenal as the ultimate ace card to deter and threaten its adversaries, but Israel’s success in defending itself against hundreds of Iranian projectiles raised doubts about Tehran’s military power. In an editorial for The Wall Street Journal, a former commander of U.S. Central Command argued that Iran’s aerial assault was a display of weakness.

“The vulnerability of Iran’s force has been exposed, and the regime is gravely weakened as a result,” retired Marine Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. wrote. “Israel has been strengthened by a stunning display of military competence, a striking contrast with that seen on Oct. 7.”

An aerial assault on Saudi Arabia by Iranian-backed Houthi forces in 2019, which the U.S. and Israel blamed on Iran, was much more effective. In that attack, which Iran denied responsibility for, drones struck key Saudi oil facilities, penetrating Riyadh’s U.S.-made air defense systems. The episode sparked concern in Washington and the region that Iran’s missile and drone fleets posed a growing threat.

In many respects, Iran and Israel have been on a collision course for nearly half a century.

Israel and Iran have been enemies since the Islamic Revolution in the late 1970s. Iran’s theocratic regime has vowed to wipe the Jewish state off the map; Israel and the U.S. have long accused Tehran of funding terrorist organizations and armed proxies in the Middle East, including Hamas and Hezbollah.

But the hostilities between Israel and Iran have never risen to the level of face-to-face military confrontation. Instead, the two countries have carried out furtive attacks on each other by land, sea, air — and cyberspace.

Iran routinely targets Israel through its “Axis of Resistance,” a network that extends Tehran’s influence across the Arab world.

While Iran has denied that it played a role in Hamas’ Oct. 7 terrorist attack, and a senior Hamas official has said Iran did not order or sanction the operation, both Israel and the United States say Tehran was complicit in the assault, having armed and trained the militants for years.

In the aftermath of Oct. 7, Israel concluded that its past targeting of Iranian arms shipments to Hezbollah in Lebanon and other covert actions had failed to sufficiently deter Iran, prompting it to go after the Revolutionary Guard officers at the diplomatic compound in Damascus this month, former U.S. officials and regional experts said.

It is rare for Iran to deploy its capabilities so directly against an enemy, even when its senior commanders are taken out. In 2020, when the U.S. launched a drone strike in Baghdad that killed Tehran’s powerful Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Iran struck back with missiles on Iraqi bases housing American troops, injuring about 100 personnel.

The war in Gaza raised tensions between Iran and Israel to new heights, before the Israeli strike on Tehran’s diplomatic compound in Damascus on April 1 killed at least seven of its military officers, including two top commanders.

Iran vowed vengeance — and then delivered on that promise Saturday. The question now is how Israel chooses to deliver its response.

Recent Comments