In the tumultuous global landscape of 2020, everything about Jacinda Ardern seems opposite.

It’s not just that she won reelection this weekend as prime minister of New Zealand, a place seemingly about as far removed from Washington geographically as it is politically.

Ardern, 40, stands almost alone as having all but eradicated community transmission of Covid-19. While the coronavirus rages elsewhere, New Zealand has become something of a parallel universe where lockdowns, masks and social distancing are no longer necessary.

Even before the pandemic, she had become a darling of liberals around the world for her compassionate reaction to the Christchurch mosques attack that killed 51 worshipers last year.

She gained further acclaim after becoming just the second world leader to have a baby while in office — and taking her infant into the chamber of the United Nations General Assembly.

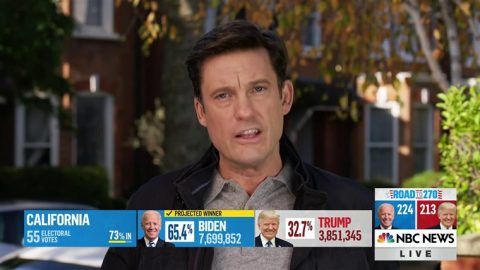

In short, as leader of the center-left Labour Party her image couldn’t cut a starker contrast to nationalists and populists such as President Donald Trump. So viewed from abroad her historic reelection is all the more notable, securing 49 percent of the vote and a majority of seats in Parliament — considered a landslide in New Zealand’s coalition-dominated politics.

“This kind of landslide should be almost impossible under New Zealand’s system of proportional representation,” said Harshan Kumarasingham, a New Zealander who teaches politics at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. “It’s very difficult for any one party to get the majority that she has, and normally they would have to go into coalition.”

Not only did voters hand Ardern Labour’s biggest win in 50 years, they roundly rejected the populist New Zealand First party and Advance NZ, a new group that has been accused of spreading misinformation this campaign. Both failed to win any seats at all.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

She now has enough seats to govern alone, but she has still decided to meet with the Green Party to burnish her credentials as “a consensus builder,” as she put it Monday.

That’s not to say her first term has been without its critics.

She has been accused of failing to tackle child poverty, an issue New Zealand scores poorly on compared to other high-income countries, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Almost 25 percent of children in New Zealand live in poverty, according to a Unicef study this year, less than the United States but more than 31 other rich nations included in the study, such as Iceland, Demark and South Korea.

And — despite generating excitement by wearing a Māori cloak when meeting Queen Elizabth II in 2018 — she has been criticized for not addressing inequality among the Māori population.

Although inequalities have decreased in recent years, Māori people — the original inhabitants of New Zealand before European settlers arrived in the 18th century — still have lower incomes, worse housing conditions and poorer health than their non-Māori counterparts, according to the New Zealand government.

“She is seen abroad as this inspiring figure because of her approach that’s so different to what’s happening in a lot of other places,” said Tom O’Brien, a former official in the New Zealand Ministry of Health who now teaches political sociology at the University of York in England.

“But back home it’s much more of an everyday kind of politics,” he said. “She just happens to be the prime minister, she needs to get on with the job. She succeeds in some policies; others, she doesn’t do quite so well.”

However Ardern’s success has less to do with her election manifesto, Kumarasingham said, but rather her overall style as a responsible leader who has the country’s best interests at heart. That, and her perceived status as the world’s lone conqueror of the coronavirus.

“At a time where there’s lots of instability and fear, I think most New Zealanders like the fact that she is clearly a good person,” Kumarasingham said, “someone who’s unlikely to do anything radical that would upset a minority or majority of the population.”

Darling of the world’s left

Among those on the left-of-center, Ardern’s star could hardly be higher.

Last year, she won plaudits for swiftly banning assault rifles in New Zealand after the Christchurch massacre. Ardern wore a headscarf while laying flowers at the scene and consoling grieving relatives.

She was only the second world leader to give birth while in office (after Pakistan’s late prime minister, Benazir Bhutto). And she gained international eyeballs again after the deadly eruption of the White Island volcano, when photographs of her embracing first responders were beamed around the world.

But it was her response to Covid-19 that appears to have fueled her romping election victory.

Back in February, polls showed that the right-of-center National Party was in the lead. But already, despite having no recorded cases, Ardern had banned entry into the country to any foreigner coming from or via China.

She said she made “no apologies” for the measures, which soon included closing the borders to all non-citizens and non-residents, and imposing quarantines even for returning kiwis.

Today, New Zealand has had less than 1,900 confirmed coronavirus cases and just 25 deaths. That’s around 320 cases per million — compared with around 25,000 per million in the United States.

It’s tough to make direct comparisons with New Zealand, a sparsely populated, geographically isolated group of islands with no land borders. The pandemic has also pushed the country into its deepest economic recession in decades.

That’s not stopped Ardern becoming cast by liberals as an antithesis to Trump and other nationalist leaders such as Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

Her down-to-earth style is made possible in New Zealand because of what Kumarasingham calls the country’s “intimate democracy.” Its smaller population and simple system of government means that the polarization seen in other countries — where politicians are either loathed or worshipped — is largely absent.

“New Zealand has long been seen as a haven against the excesses of politics,” he said. “It’s normal here to have ‘normal people’ as prime ministers. The thing that’s different now is the profile that Ardern has gained overseas.”

Recent Comments