JERUSALEM — Abuses against Palestinians held in Israeli jails have risen since Hamas‘ Oct. 7 attacks, former detainees and rights organizations have warned, with one group alleging that prison officers are taking “revenge” on inmates for the militant group’s atrocities.

Data compiled by Israeli rights group HaMoked said the number of “security inmates” — prisoners detained on grounds of national security — had jumped 66% to 8,600 in January from 5,192 in October, adding the majority are Palestinians. The Israel Prison Service did not respond when asked for prisoner numbers.

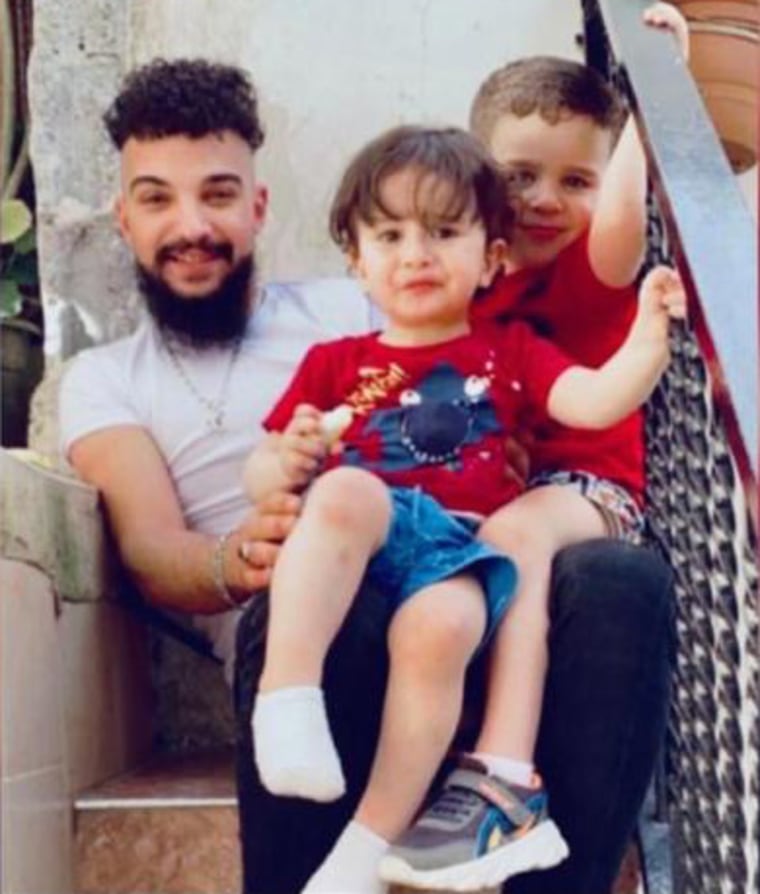

One security inmate was Ramzi Abbasi, 30, who was arrested last spring and accused of communicating with a Hamas-affiliated group — charges he denies.

He said life in Ktzi’ot Prison became progressively worse after 1,200 Israelis were killed and 240 taken hostage during Hamas’ multipronged attacks on Israel. Israeli officials say around 100 people still remain in captivity after scores were released in late November as part of an exchange for Palestinian prisoners. More than 25,000 people have been killed since Israel launched its military assault on Gaza, according to the enclave’s health ministry.

“Our life became zero. We didn’t mean anything to them,” Abbasi, now released, said in the backyard of his east Jerusalem home overlooking the Old City. “They treated us less than the animals. Beating, abusing, torturing, everything you could imagine.”

“I was sexually harassed,” he said, adding he also witnessed guards sodomize his cellmates with truncheons. NBC News has not been able to corroborate his allegations.

Prisoners were regularly stripped naked and piled on top of each other for the guards’ amusement, he said. “They were happy, enjoying what they were doing to us,” he said, adding that none of the abuse seemed aimed at extracting information or a confession.

Abbasi, a physiotherapist, said he was released in November one month early, to make room for the huge numbers of inmates arrested by Israel after Oct. 7.

The Israel Prison Service said in a statement to NBC News last month that they were “not aware” of Abbasi’s complaints and that “as far as we know, no such events have occurred.” It did not comment when asked why he was released.

The prison service has acknowledged that it made recent changes. In a statement published shortly after the attacks in October, officials said they “decided to reduce the living conditions of the security prisoners” like Abbasi.

The new policy means such prisoners would “enter a ‘locked’ state (closed in cells), reduce movements and prevent contact with the outside world,” the statement said, adding the measures were meant to take “into account the exceptional security situation prevailing in the country.”

Rights groups say the “security prisoner” designation is broad and can apply to crimes ranging from stone throwing to handling explosives and aiding and abetting terrorists. Israel’s prison service did not respond to an NBC News request to define the charge.

The statement was released on Oct. 17, the day before Israeli lawmakers passed emergency legislation allowing prisoners to be housed in conditions that would be otherwise considered illegal. This was extended by the country’s National Security Committee last month.

Abbasi’s complaints echo those of other prisoners and rights groups who have long condemned Israel’s treatment of detainees, but say that prison conditions have deteriorated since the attacks.

“What we’ve seen in the prison service now is revenge,” said Tal Steiner, an attorney and the executive director of the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel, an Israeli nongovernmental organization that monitors the treatment of Palestinian prisoners.

“There is a sense in the system that things are more allowed — that expressing that anger towards them, that vengefulness, is somehow allowed,” she said, adding that her organization had received reports from prisoners about sexual assault, humiliation and degradation while they were behind bars.

Asked about these comments, a prison service spokesperson said it “operates according to the provisions of the law,” and “all basic rights required are fully applied.”

Steiner said some of the measures could be explained by having to handle more prisoners, “but other things, other phenomenons that we’ve seen … sexual assault, humiliation and degradation, what does that serve? That’s absolutely just people, very angry and frustrated and being able and being allowed to express that anger beyond what they’re supposed to be doing.”

While many were detained by police or the Israeli Security Agency, the internal security service known as Shin Bet, increasing numbers of Palestinians have also been detained by the country’s military.

Israel Defense Forces detainees in the Gaza Strip interviewed by NBC News after they were freed last month said they were beaten; deprived of food, water and toilet facilities; and subjected to cruel and humiliating treatment, such as being stripped naked and exposed to cold temperatures and deprived of sleep. They said they had been questioned about the location of Hamas tunnels.

“I was beaten so badly I just wanted to die,” one of them, Khamis Albardini, 55, said, breaking into tears as he was treated with other detainees for wounds they accused their captors of inflicting. NBC News witnessed deep, bloody gouges around their wrists and a doctor said some had fractured bones. Albardini was not charged with a crime.

NBC News could not independently verify their claims. But social media footage circulating since Oct. 7 and verified by NBC News showed Israeli forces guarding blindfolded, naked and near-naked detainees, and in some instances striking them.

The IDF said in several statements that it treats detainees “in accordance with international law” and often asks suspects to undress to search their clothes and ensure they are not concealing explosive vests.

Abbasi, the former security inmate, said when he left prison in November, he was almost 29 pounds lighter and had three broken ribs.

The psychological scars remain.

“Every day, I dream of the jail,” he said. “They think they will break us when they do this to us; no, we are unbreakable. But in the end, we are humans. At night, I dream and remember everything they did to me. I can’t forget what happened to me.”

Eventually he said he would like to see his torturers punished, but acknowledged that the chances seem low.

Of the 1,400 torture complaints filed between 2001 and 2022 against the Israeli Security Agency, only three led to criminal investigations and none to a single indictment, according to the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel.

Deaths in custody have increased as well. In the three months since Oct. 7, at least seven people have died in Israeli prisons compared to two or three per year before the attacks, said Steiner, the NGO’s executive director, citing publicly available data.

Abdel Rahman Al Bhash, 23, died on New Year’s Day in Megiddo Prison, where he was around halfway through a three-year sentence for “shooting at people, contact with a hostile organization, military crimes and throwing an object meant to set fire,” according to Israel’s Prisons Service.

Officials have yet to offer an explanation for Bhash’s death, nor have they turned his body over to his parents, but the prison service said the circumstances of his death “will be reviewed.”

Bhash’s father, Bassim, said that after speaking with some of his son’s fellow cellmates who told him about the beatings and starvation, he was convinced that he had died at the hands of his jailers.

“I felt that something was wrong. I felt him shouting my name and telling me, ‘Mother, I am hungry, come, mother,’” Bhash’s mother, Sameera, said. “I could feel him being tortured.”

Both remain skeptical about whether they will ever learn the full circumstances surrounding their son’s death.

For Steiner, the worry is that Israel is creating more determined opponents by treating prisoners badly, raising a new generation of would-be terrorists.

“My concern is that what we’re seeing is an Israeli Guantanamo,” she said, referring to the American base in Cuba where terrorism suspects from foreign countries have been detained for more than 20 years.

“This kind of phenomenon will echo years ahead,” she added. “People who have been tortured are radicalized.”

Recent Comments